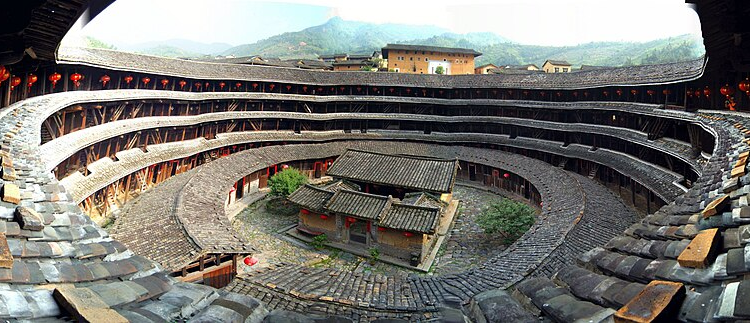

In the 1970s, nestled amidst the misty hills of Fujian, stood round, serene fortresses crafted from compacted earth—tulou, the ancestral abodes of Hakka and Minnan families. Viewed from above, they resembled colossal coins gently placed upon the mountains. Inside, however, they felt like miniature cosmoses, with each family revolving around the communal core of a central courtyard.

My mother grew up in one.

Back then, there were no locks on doors. Everyone knew which room belonged to which family, who cooked the best fish soup, who had the cleanest balcony, whose baby wouldn’t sleep through the night. She would wake to the sound of roosters, run barefoot on cool wooden floors, and eat breakfast with the noise of a dozen families rising around her.

Each household had one room per floor—living space below, sleeping quarters above, dreams somewhere in between. The courtyard wasn’t just a space between walls. It was the stage of daily life. Grandmothers peeled vegetables under the sun while children played hide-and-seek around the well. Weddings were celebrated with paper lanterns strung from every balcony, while funerals brought the community to a hush that even the chickens seemed to understand.

The tulou taught its residents how to live together—not just next to each other. You didn’t need to knock to visit a neighbor; you just arrived. When someone was ill, rice porridge would appear at their door, unsolicited. When a harvest was good, it was shared. There were no secrets, really. And strangely, no shame in that. Everything was heard. Everything was seen. And in being seen, people were held.

The 1970s were not easy years. The country was changing. Jobs were scarce. Some families began to talk of “leaving the mountains” to find work in cities. But still, for a while longer, the tulou held on. Even as transistor radios arrived, even as a single phone was installed at the village station, even as letters came from sons working far away—this place stayed the same. Its walls curved around every argument, every reunion, every steaming bowl of rice placed on a shared table.

When my mother eventually left, she took almost nothing with her. But she carried the sound of sweeping brooms in the corridor, the smell of smoked tofu drifting through bamboo windows, the warmth of evening light settling on communal stone steps. These stayed with her—intact, unbroken—long after she learned to live in the square silence of a city apartment.

Today, many of those tulou stand empty. The echoes are still there, if you listen closely: a child’s footsteps, the creak of wooden stairs, laughter rising from the courtyard in late summer. Tourists walk through now with cameras, reading plaques, admiring the architecture. But they rarely ask who once lived behind the doors. They don’t know which rooms were swept daily by the widow in unit six. Or where the red string was hung to celebrate a birth.

But those of us who remember—those of us born from that circle—we know. We carry the map in our bones.

The tulou wasn’t just a house. It was a way of being. It taught us to live in proximity, not only in space but in spirit. It gave us a rhythm: not of solitude, but of shared time. And even now, in our private, walled-off lives, that rhythm lingers.

Somewhere between the echo of firecrackers and the rustle of drying peanuts, the round walls still breathe.