Many people might not know this,

but as early as over a hundred years ago,

Fuzhou already had its own version of “Alipay.”

Before the First Sino-Japanese War,

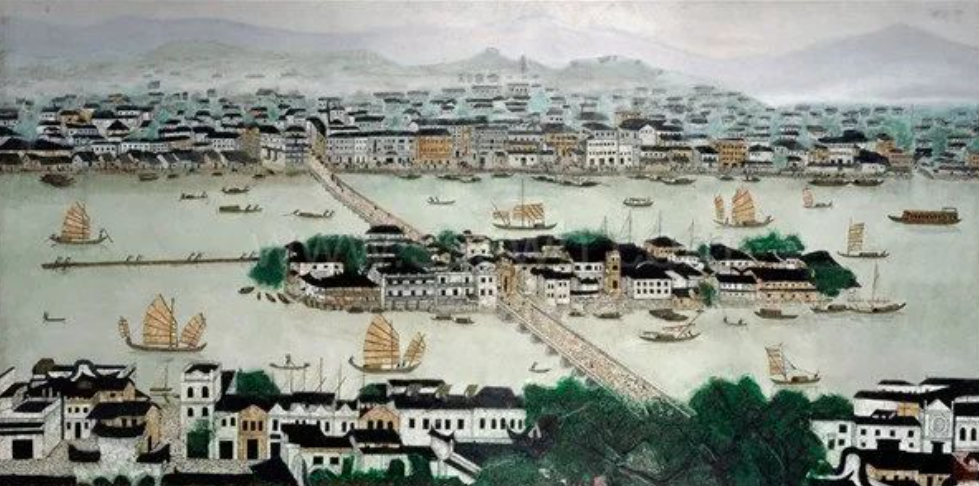

most of Fujian’s money exchange shops (known as qianzhuang) were concentrated in Fuzhou,

especially in the area of Shangxiahang.

According to historical records, during the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China era,

there were over 110 qianzhuang operating in Shangxiahang alone.

Of these, the qianzhuang on Shanghang Street accounted for one-third of all such shops in the entire city—

truly a place where money changers gathered in great numbers.

Today, let’s take a closer look at this fascinating piece of history.

In the late Qing Dynasty,

“establishing factories for self-reliance” and “boycotting foreign goods” became an emerging trend.

The movement promoted the development of national industries,

which in turn led to the flourishing of loan and capital turnover services in Fuzhou.

After the port of Fuzhou was opened in 1844,

foreign merchants arrived and discovered that there were nearly a hundred large and small qianzhuang (money exchange shops) operating in the city.

Most of these qianzhuang possessed significant capital and offered services such as accepting deposits and issuing bills.

Around 1860, twelve of Fuzhou’s qianzhuang held capital ranging between 150,000 to 200,000 taels of silver.

In the early years of the Guangxu Emperor’s reign,

a merchant from northern Fujian established the “Shiyu Qianzhuang” on Xiahang Street,

with a capital exceeding two million silver dollars, making it a financial powerhouse that caused a sensation in Rongcheng (Fuzhou).

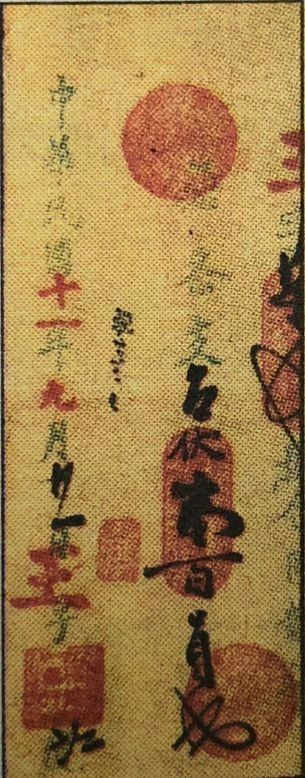

At that time, the financial notes (qianpiao) did not have a pre-printed denomination.

Instead, the amount, date, serial number, and shop seal were handwritten or stamped on a blank printed template at the time of issuance.

The face value of these notes ranged from as low as 400 copper coins to as high as 500 guan (stringed coins).

These notes offered great convenience in payments,

and were essentially Fuzhou’s version of “Alipay” in that era.

Before the emergence of modern banks,

these qianzhuang almost singlehandedly supported financial circulation for imported foreign goods and the export of local products.

During the prosperous era of Fujian’s tea industry, they became indispensable financial institutions.

The British Parliament’s Blue Book of 1847–1848 even featured a dedicated discussion on Fuzhou,

in which the British remarked: “Fuzhou’s financial system, without a doubt, is clear proof of the city’s advanced commercial and trade development.”

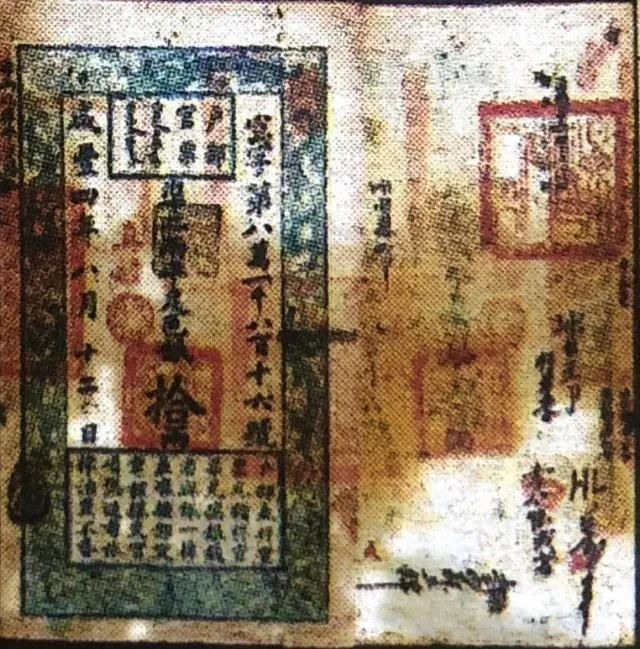

In the 30th year of the Guangxu reign (1904), financial notes saw further innovation with the introduction of the “Taifu Note” (Taifu Piao).

The name “Taifu” reflected both geography and local culture: “Tai” referred to South Tai, a district in Fuzhou, while “Fu” was a phonetic abbreviation and homophone for “Fo,” short for Fotoujiao—a silver coin imported from Hong Kong and popularly used in the area.

Thus, “Taifu Note” essentially referred to silver dollar notes issued in Fuzhou.

At the time, one Taifu Note was equivalent in value to one silver dollar, or roughly 1,000 copper coins.

In 1844, Fuzhou officially opened as one of the “Five Treaty Ports” under the Treaty of Nanking.

By 1845, the British had established a consulate on Nantai Island, and the riverside areas of Taijiang—including Shanghang and Xiahang—soon became major centers for import and export trade.

In the first year of the Xianfeng Emperor’s reign (1851), a new provincial governor arrived in Fujian—Wang Yide.

At that time, the provincial governor held the title xunfu, with a rank of second-class senior official (Cong Erpin).

Concerned about national economic issues, Wang Yide observed the evolving economic situation for several months,

and in 1852, he submitted a memorial to the emperor, using the financial practices of Shangxiahang in Fuzhou as a model to solve the imperial court’s pressing monetary challenges.

This memorial was later summarized in Volume 427 of the Draft History of Qing (Qing Shi Gao), which stated:

“With rising expenses due to increasing coastal defense efforts… instead of seeking more silver, it would be better to reform the system and promote the use of official banknotes… In various regions of Fujian, silver, copper coins, and commercial notes circulate interchangeably, making transactions convenient and reliable. Merchants and citizens alike have embraced paper currency. Moreover, as the sovereign of the realm, the imperial treasury carries weight—issuing baochao (treasury notes) would facilitate circulation. The format of the notes should be simple, based on the tael unit, distributed through provincial treasuries, and made known to the public. They could even be used to pay taxes and grain levies without obstruction.”

During the Qing dynasty, silver was the primary currency in circulation, but it was difficult to mint and transport.

Drawing from the success of Fuzhou’s qianpiao system, Wang Yide proposed issuing government-backed notes under the authority of the imperial treasury.

This would allow taxes across various regions to be paid in notes, making financial transactions significantly more convenient.

The Draft History of Qing also recorded Emperor Xianfeng’s approval:

“Memorial received. Instructed the Grand Council and Ministry of Revenue to discuss and implement. Appoint Wang Yide as acting Governor-General of Fujian and Zhejiang.”

After praising Wang Yide’s proposal, Emperor Xianfeng ordered the Grand Council and economic officials from the Ministry of Revenue to discuss its execution.

At the time, Wu Wenyong, Governor-General of Yunnan and Guizhou, was originally slated to replace Wang Yide in Fujian and serve as Governor-General of Fujian and Zhejiang.

However, before taking office, Wu was reassigned to fight the Taiping Rebellion as Governor-General of Huguang.

Seizing the opportunity to reward Wang Yide, Emperor Xianfeng allowed him to concurrently hold the position of Governor-General.

Clearly, Wang Yide’s financial practices in Fuzhou proved highly effective.

In the fourth year of Xianfeng’s reign, he was officially promoted to Governor-General of Fujian and Zhejiang—a prestigious Zheng Erpin (second-class senior) position—which he held for five years.

By submitting a single proposal grounded in Fuzhou’s experience, Wang Yide earned a full-grade promotion.