It was the end of 2024, yet few seemed to notice that a full quarter of the 21st century was quietly approaching its close. Instead, what filled conversations was something else entirely. People were saying: it feels like we’ve returned to the 1980s.

An American election awash in red. Eastern Europe resisting Russian influence. Israeli airstrikes in Lebanon. Martial law in South Korea. Chinese communities once again arguing about Chiung Yao.

Reality swings like a pendulum. In the intensity of the moment, it often pulls us back—to memories, to feelings, to years that felt more alive than others. But why does it always take us back to the 1980s? Why not another decade?

What made the 1980s feel so distinct, so unforgettable?

That decade was both gritty and romantic. It was a time when things were opening up, when emotions were allowed to be spoken out loud. Thought ran free. Debate was everywhere. It was a moment in history when idealism wasn’t just tolerated—it was expected.

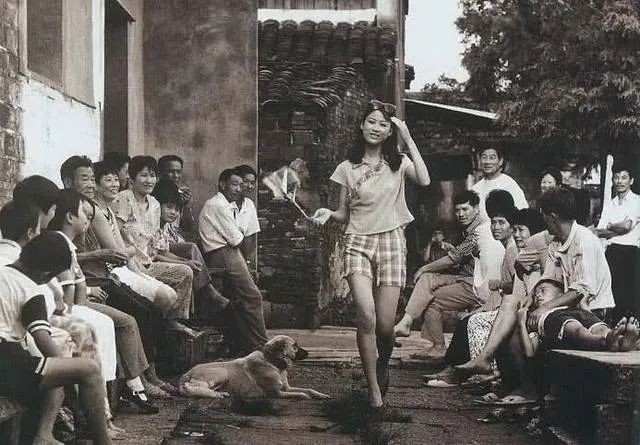

If we had to describe the 1980s in three words, maybe they would be: young, honest, and pure. There was a kind of gentle intensity in how people lived. The idealism and passion of that time became a quiet utopia for both intellectuals and everyday people.

The 1980s carried a feeling not unlike the early days of spring. Everything was just waking up. There was freshness in the air. It felt like the world was smiling for the first time in a long while.

People lived slower. Needs were simpler. Smiles were genuine. Love was something that held weight. It was a time when a promise was something to live by for a lifetime.

For literature, the 1980s was something golden, something that can never quite be recreated. In the wave of openness, a generation of writers, poets, and thinkers emerged and shaped what it meant to write again.

That decade gave us real voices—writers with backbone, scholars with ideas, culture with texture. Literature didn’t worry about where something came from. It welcomed everything. It was the hunger of a society that had been closed off, now opening its eyes to the world.

From the scar literature of wounded memories to the reform literature looking forward, names came pouring in—Wang Meng, Lu Yao, Liu Xinwu, Jia Pingwa, Yu Hua, Su Tong, Fang Fang, Shi Tiesheng, Liang Xiaosheng, Wang Shuo, Mo Yan, Chen Zhongshi.

They looked back, they looked forward, they dared to speak of the present. It was like a sky full of stars—bright, unfiltered, unforgettable.

As the earth awakened and spring returned to all things, in a season full of hope, those once-silent poets began to reflect on life and dream about ideals. The dreams of poets belonged to the 1980s—dreams about love, about belief. When one read poetry back then, admiring, longing glances were still present in the room.

Before the tide of materialism arrived, a single pot of hot liquor was enough to open up conversations that felt endless and boundless. A few drinks in, there was nothing that couldn’t be said. There was trust, as effortless and fluid as mountain streams, as simple as true companionship.

Bei Dao brought a sharp edge and introspection in The Answer:

“Despicableness is the passport of the despicable,

Nobleness is the epitaph of the noble.

Look—in the golden sky

Float the twisted shadows of the dead.”

Shu Ting’s delicacy and clarity shone in To the Oak:

“I must be a kapok tree by your side,

Standing with you as a symbol of strength.

Our roots grip tightly underground,

Our leaves touch high in the clouds.”

Gu Cheng spoke of contradiction and hope in A Generation:

“The dark night has given me black eyes,

But I use them to seek the light.”

Mang Ke was pure and raw in Sky:

“The sun rises. The sky is bleeding red,

Like a shield split wide open.

Days are exiled like prisoners—

No one asks me anything. No one forgives me.”

And then there was Haizi, with his romance and spiritual longing in Facing the Sea, with Spring Blossoms:

“From tomorrow on, I will be a happy person.

Feed the horses, chop wood, travel the world.

From tomorrow on, I will care for food and vegetables.

I have a house,

Facing the sea, with spring blossoms.”

In The Polish Visitor, Bei Dao once sighed:

“Back then, we had dreams—about literature, about love,

about traveling the world.

Now, we drink deep into the night.

When our glasses clink,

It sounds like the breaking of dreams.”

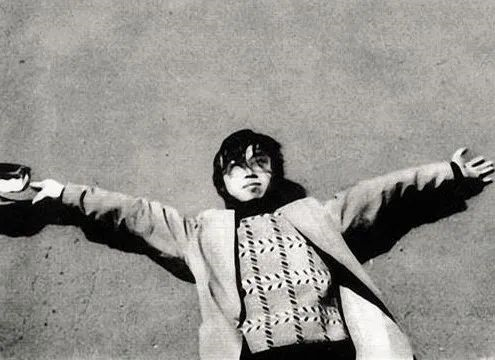

Haizi’s ideals collapsed—he lay on the tracks and ended his life.

Gu Cheng’s sky caved in—he took his partner’s life and then his own.

Mang Ke turned to painting as a way to survive.

Bei Dao left for Europe, preserving his poetic kingdom from afar.

The poets had gone.

Poetry itself had died.

What followed was an era of restlessness and noise—an age of dazzling confusion.

That era was rich with both tender love stories and legendary tales of wandering swordsmen roaming the world with blades in hand and righteousness in their hearts.

There were the romantic dramas of Chiung Yao and Yi Shu, the drifting passion of Sanmao, and the gallant chivalry of the three masters of wuxia—Jin Yong, Liang Yusheng, and Gu Long—who filled the martial world with honor, revenge, and undying loyalty.

Yi Shu’s cashmere sweaters were always symbols of urban independence and elegance. The men and women in her stories made grand promises of eternal love, sweeping and emotional, yet ultimately resigned to helplessness. Her writing captured the tangled affections and bittersweet romances of city dwellers with bourgeois sensibilities.

Sanmao stood in the desert wind wearing a long dress adorned with bold floral patterns, her black hair flying in the sandstorm. With the spirit of a gypsy woman, she searched across continents for a place where her soul and love could rest. Her love story with the bearded José—so long, so bound by life and death—once brought countless readers to tears. It awakened a longing for the poetic and the distant, for flowers that bloom and fall in the dreams of wanderers.

It has often been said: wherever there are Chinese people, there are Jin Yong’s martial arts novels. Jin Yong’s legendary pen described life with profound insight. His characters—heroes and heroines, villains and vagabonds—shaped, often unconsciously, the most basic concepts of justice and love for generations of readers.

For many Chinese, their earliest understanding of loyalty and righteousness comes from Jin Yong’s world of swords and honor.

Someone once asked Jin Yong, “How should one live a life?”

Jin Yong replied, “Create a storm, then leave in silence.”

Heroes represented the spirit of integrity and responsibility. In the era of reform and opening up, the 1980s especially called for bold heroes who could cut through complexity and forge new paths.

During this period, not only did the Chinese mainland produce a number of meticulously crafted films and television dramas, but many classic titles were also imported from Japan, Europe, America, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. These works became a major source of spiritual enjoyment and lasting memories for people in the 1980s during their leisure time.

The television drama The Bund (Shanghai Tan) moved audiences with its thrilling tale of vengeance and chivalry set in a turbulent underworld. Its impact was so powerful that it caused near-empty streets during broadcast hours. In a public poll held in Hong Kong, The Bund ranked first, rightfully earning its place as a true classic of the era. The lead characters, Xu Wenqiang and Feng Chengcheng—played by Chow Yun-fat and Angie Chiu—became iconic symbols of their generation.

The image of “Xu Wenqiang” in a black fedora, trench coat, white gloves, and a flowing white scarf exuded charm and masculinity, becoming the ultimate dream figure for countless young women.

Feng Chengcheng, with her braided hair and youthful blush, carried both shyness and spirit—pure, strong, and decisive. She became a treasured figure in many people’s memories of that innocent time. The brilliant performances of Chow Yun-fat, Angie Chiu, and Ray Lui gave life to the emotional highs and lows of The Bund, making its story of love and revenge utterly gripping. The stirring theme song performed by Frances Yip became inseparable from the series and helped cement its legendary status.

The 1986 version of Journey to the West (Xi You Ji) caused a nationwide sensation. Universally praised, it has since become recognized as an unsurpassable classic. Journey to the West became a must-watch for generations and remains a collective television memory in the hearts of Chinese viewers.

Journey to the West symbolized the vitality and spirit of challenge that defined the 1980s.

It was a classic heroic and inspirational series that, in a decade calling for bold exploration and innovation, resonated deeply with people’s longing for heroism.

Among the foreign TV dramas introduced to mainland China during the 1980s, one American series stood out for how powerfully it gripped the audience’s imagination—Garrison’s Gorillas. This show told the thrilling story of a group of prisoners released from jail during World War II who used wit and bravery to carry out dangerous missions behind enemy lines, repeatedly achieving miraculous victories.

At the time, it was one of the very few American television series imported into China. Each episode was a self-contained story, packed with unpredictable twists, high-stakes drama, and adrenaline-filled action. Its suspenseful and captivating plots left a deep impression on viewers.

In an era when there were still few films and TV programs available, the sheer appeal and entertainment value of Garrison’s Gorillas made it an exceptionally popular and memorable show.

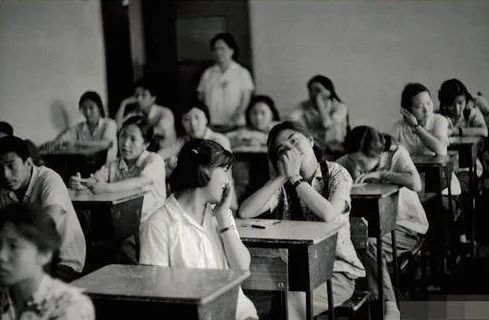

Back then, we were still students. Almost every time, we watched the show through the window of the school store—utterly engrossed, savoring every moment. We were fascinated by the characters in the story, unable to tear ourselves away. We didn’t really feel the cruelty of World War II depicted in the setting; instead, it all seemed adventurous and exciting.

After graduating from college, the fascination hadn’t faded. I even went online and downloaded the entire series.

The opening music of each episode was intense and gripping. The moment it started playing, it tightened the mood and pulled the audience right into the suspenseful ups and downs of the plot, preparing us to enjoy yet another thrilling feast of storytelling.

The dashing Lieutenant Garrison—with his commanding presence and piercing eyes—left a lasting impression. His signature line, “I’m Lieutenant Garrison,” remains unforgettable to this day.

In the 1980s, the most iconic achievement was undoubtedly the Chinese women’s volleyball team winning five consecutive world championships. The team’s star spiker, Lang Ping, earned the nickname “Iron Hammer” for her powerful playing style. From that time on, the term “Spirit of the Women’s Volleyball Team” came into use, symbolizing relentless hard work, perseverance, and tenacity. It ignited patriotic fervor across the nation and became a model of excellence for generations to learn from.

The five-time championship of the women’s volleyball team was perhaps the most morale-boosting event for Chinese people during the 1980s. At the time, when students wrote essays about hard work and striving for success, the heroic story of the women’s volleyball team was frequently used as an example—it practically became a standard reference.

In the world of sports during the 1980s, the other great source of pride was Chinese football. That era is widely considered one of the best periods in the history of the national men’s team. Outstanding players like Gu Guangming, Chen Jingang, Shen Xiangfu, and Jia Xiuquan, along with top coaches such as Su Yongshun and Zeng Xuelin, helped elevate the performance and reputation of Chinese football to new heights.

At that time, there was no “Korea phobia” or fear of the Japanese team. China was firmly ranked among the top teams in Asia. Fans watched games with confidence, without anxiety or apprehension. The fearless spirit of that era—the bold, youthful attitude of not fearing any opponent and daring to challenge the best—remains a cherished memory to this day.

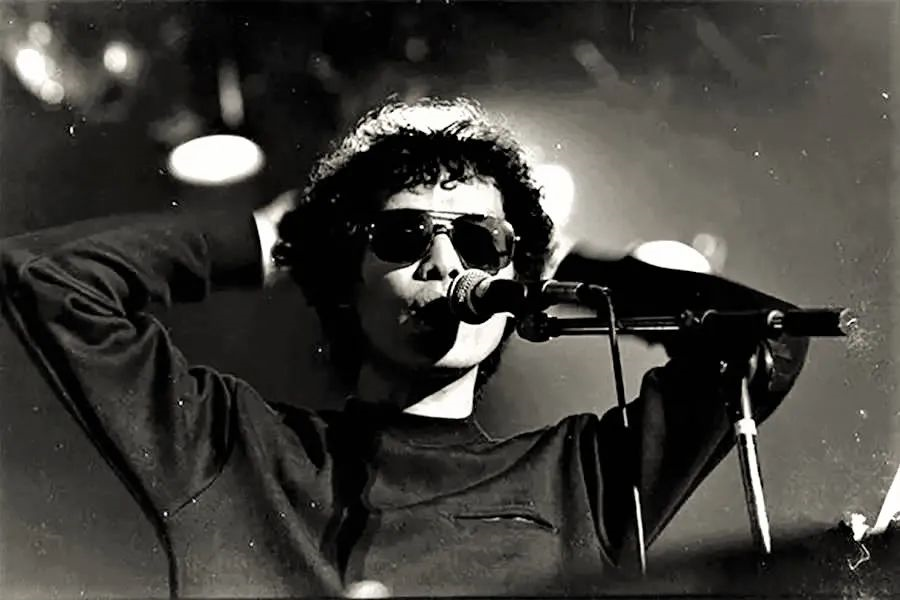

In the early years of China’s reform and opening-up during the 1980s, the world of pop music opened its arms to global influences. Especially notable was the influx of pop music from Hong Kong and Taiwan, which greatly enriched the mainland’s pop music scene and directly contributed to the growth and evolution of original Chinese music.

The pop songs from Hong Kong and Taiwan swept across the mainland like a fresh breeze, deeply resonating with young people’s desire for individuality and emotional expression. From the north to the south, portable cassette players blared pop music through streets and alleys, making people feel as if spring itself was flowing through their ears—captivating, intoxicating.

At that time, the fashionable image of a young person was unmistakable: a denim or flared pants outfit, a floral-patterned white shirt, a permed afro hairstyle, a pair of sunglasses, and popular tunes humming on their lips. In the garden of pop music, the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan bloomed like three vibrant flowers—competing in brilliance, yet complementing each other, creating a dazzling mosaic of sound and culture.

Many iconic musicians—such as Jonathan Lee, Chyi Chin, Su Rui, and Jay Chou—openly admired Lo Ta-yu. He was rightfully honored as the Godfather of Taiwanese Music, a title he richly deserved and widely recognized.

Campus folk songs, which originated in Japan and flourished in Taiwan, were introduced to the mainland during the 1980s. They brought a poetic freshness to the relatively plain pop music of the mainland and directly gave rise to the popularity of campus ballads in the 1990s.

The 1980s were like a dream—imperfect and not affluent, but emotionally rich and spiritually fulfilled. Though life was simple, it was anything but ordinary. In literature, music, film, thought, entertainment, and sports, every field was alive with energy and diversity. After decades of suppression and chaos, people were filled with hope, driven by ideals, brimming with enthusiasm, and eager to embrace everything new. It was a rare time of true flourishing.

The 1980s were a time of awakening, of vibrant energy, of vivid color, and of priceless memories.

Back then, young people had no money, but even when standing in front of powerful officials, they dared to say: “So what if you have money?”

No one says that anymore.

Today’s youth understand all too well: no matter how strong your personality, it’s never stronger than society; and no matter how noble your ideals, they can’t pay next month’s bills.

As times changed drastically, the world today bears little resemblance to the past. The 1980s, too, have gradually faded away amidst the spread of education and the tide of commercialism. What was once considered elite culture has now completely become a relic of the past.

To this day, people still long for that era—an age of openness, sentiment, poetry, and freedom of thought, where all kinds of voices bloomed like spring flowers. People of that time lived with soul. No one cared much about money or power; instead, they admired those who lived with style, those who lived with presence.

The world seems increasingly materialistic, increasingly utilitarian. There are fewer who are brave, more who are pragmatic. Fewer who rebel, more who kneel. More hands clapping, but fewer who ask why they’re clapping.

We’ve finally come to realize: ideals, spirit, freedom, independence, literature, poetry, art—all of them are no match for a plagiarized PowerPoint slide full of buzzwords. And they’re even less a match for the massive current of historical change.

It was a fleeting era, caught in the cracks of history, yet a golden age that can never return. If there was ever a time marked by ideals, belief, mission, and romance—while simultaneously driven by madness, rebellion, hunger, and chaos—it could only be the 1980s.

In the 1980s, everything had just been unshackled. Emotions, thoughts, and creativity that had been suppressed for over two decades came pouring out.

The ideological straitjacket had just been removed. The national focus shifted toward economic development. But even as commercialism spread, it did not immediately foster a society ruled purely by profit. The brilliance radiating from the cultural world at that time—when we look back three decades later—still glows with dazzling intensity.

Poet Bei Dao once said: “Looking back at the 1980s—it was loud and glorious, like a train lit up against the night sky, flashing by in a blaze of light.”

Xianzhi Bookstore specially recommends the “Looking Back at the 1980s” trilogy (with exclusive content), including:

“Me and the 1980s” by Ma Guochuan“Interviews from the 1980s” by Zha Jianying“The Glory and Dreams of China’s Economists in the 1980s” by Liu Hong

These three books form a unified whole. From the perspectives of thought, economics, and culture, they collectively paint a portrait of that era. The greatest significance of the 1980s was the liberation of thought. In order to make up for the lost decades, people eagerly absorbed knowledge from abroad, hungry to create something of their own. As a result, literature and artistic movements burst forth like stars across the sky—dazzling and unstoppable.

Aesthetic fever, guoxue revival, new enlightenment, scar literature, reportage, humanitarianism—all flourished like wild grass after a spring rain, wild and full of life. In art, the Stars Art Exhibition and waves of rock music emerged one after another.

The 1980s trilogy features figures like Ah Cheng, Chen Danqing, Wang Yuanhua, Li Zehou, Han Shaogong, Bei Dao, Liu Zaifu, Cui Jian, and Tian Zhuangzhuang—covering literature, music, fine arts, and cinema. Through the voices of these pioneers, the spirit of the cultural world during that era is fully revealed. Was the 1980s truly a unique moment in Chinese history?

These books focus on the 1980s, but they don’t stop there. The people involved were leaders in their fields—three generations of economists who contributed to reform, and cultural icons such as Tang Yijie in philosophy, Ah Cheng in literature, and Li Xianting in art. Their insights stretch the timeline, zooming in and out, helping us better understand the true significance of the 1980s.

Were the 1980s a brief spark, or can their brilliance continue? What is their true historical standing?

Some have compared the era to America’s hippie movement—the rebellious spirit was indeed similar, but the drive for progress was quite different. Others have traced its intellectual awakening back to the May Fourth Movement, evaluating the historical impact of both.

The 1980s had impulsiveness and immaturity, but above all, they were vibrant and alive. As a cultural high ground, that decade birthed many of today’s cultural foundations. Much of what we see now in the cultural scene had its seeds planted then.

Through these three books, readers can not only revisit a glorious era full of dreams, but also reflect on the present and consider the way forward for our time.