March 13, 2025, marks the 40th anniversary of my arrival in Europe.

As I look back, a flood of emotions rises. Every Qingtian emigrant carries a story worth telling.

In early 1985, I arrived in Belgium. The elder Qingtian folks treated me with remarkable warmth—some even gave me red envelopes during visits. When they found out I could tailor clothing, a few of them bought fabric from the local shops. Under the guidance of community leader Mr. Zhu, I made several suits that month. After finishing those orders, I had already paid off my plane ticket—with money left over. The old saying is true: “A skill in hand can carry you across the world.” I never changed my trade in all the decades that followed in Europe.

At the time, Spain was granting an amnesty, offering a chance to apply for legal residency. But after thorough discussions with my cousin Yang Pengmei, I decided to head to Paris instead. My top priority then was to build a financial foundation. My cousin contacted a French friend, who drove me directly to the périphérique highway around Paris. From there, a taxi took me to a restaurant in the 13th arrondissement. The restaurant’s owner, Mr. Xia, had come to Europe from Hong Kong with my cousin on the same ship. He helped me arrange both lodging and work. After that, my cousin returned to Belgium.

Paris was, and still is, the fashion capital of the world. The city had thousands of garment shops—many of them run by Jewish families. Nearly half a million people in Paris were engaged in the garment trade. Chinese garment workshops were typically small, housing dozens of sewing machines. Orders came from pattern-cutting companies, and tasks were divided into sewing, buttoning, pressing, etc. Workers were paid by piece—more work, more pay. Hours were long and the labor demanding. I remember a woman collapsing at her sewing machine from sheer exhaustion.

In the mid-1980s, waves of Chinese migrants from Zhejiang—Qingtian, Wencheng, Wenzhou—flocked to Paris. While some men sought culinary training to open restaurants, most men and women entered garment factories as machine operators. Their wages were generally higher than in other industries. But many had no legal status and worked as undocumented laborers. The French government frequently dispatched undercover labor inspectors and police to monitor Chinese workshops. Owners feared these inspections—if caught employing undocumented workers, they could face heavy fines or even jail time. To avoid risks, many factory owners moved sewing machines into their homes, allowing undocumented workers to sew garments there.

A friend surnamed Wang had his first son born in Paris. He and his wife spent years sewing from home. In 1988, when Italy began offering labor regularization, they moved to Empoli, near Florence. There, they started a garment workshop. As the birthplace of Italy’s high-end fashion industry, the area was home to many luxury brands that contracted work to them. After a decade of steady development and capital accumulation, they purchased land in Shaoxing in the early 2000s. There, they built a factory and founded the Toscania company, which became a well-known foreign-invested enterprise in the region. They even developed their own fashion brand, becoming a model of Qingtian entrepreneurs returning to China to start businesses.

But that, of course, is a story for another time.

In 1986, I was working in a garment workshop in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris, run by a fellow Qingtian native.

One day, we were suddenly warned that police were knocking at the front door. For those of us without legal residency, panic set in immediately. Everyone rushed out through a back room door, scrambling into the street in a flurry. The police, of course, were aware that the workshop had a rear exit. We all knew this place was no longer safe. If the police ever sealed off the back entrance next time, we would be trapped like fish in a barrel. So, we moved again—this time to a more discreet, hidden workshop.

This new workshop was owned by Mr. Ye, a businessman from Wenzhou whose ancestral home, however, was Gaoshi Village in Qingtian County. His father, General Ye Mai, was a graduate of the fourth class of the Huangpu Military Academy, and had been classmates with Lin Biao and Zhang Lingfu. His uncle by marriage, Zhao Zhiyao, had served as the chief of staff to General Chen Cheng and was the finance director of Hubei Province during the war against Japan.

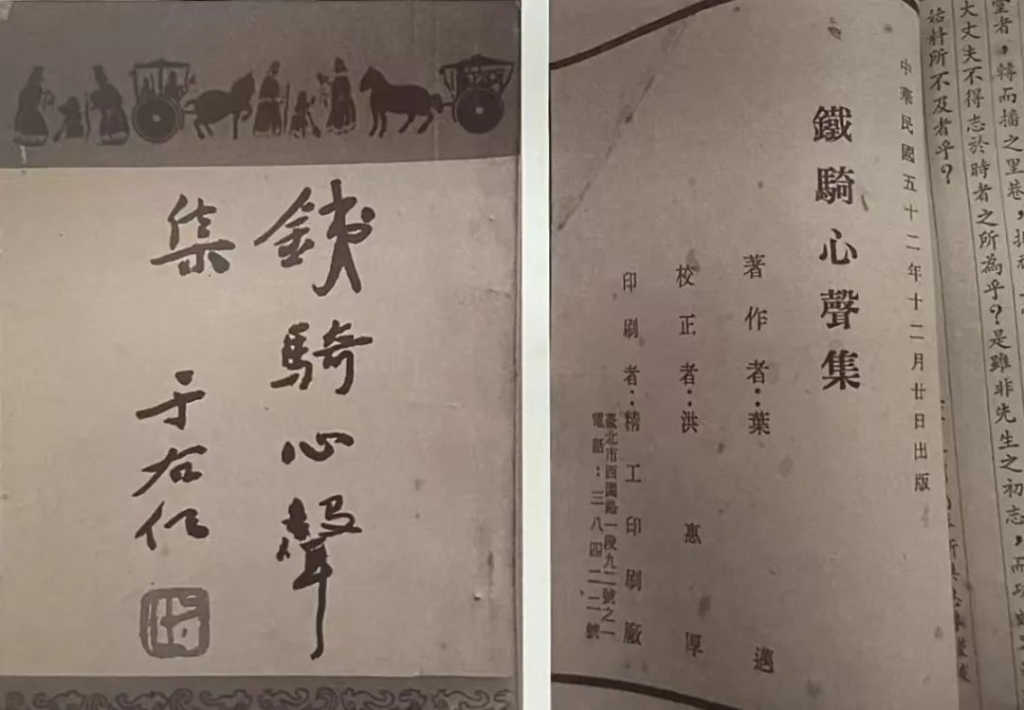

Mr. Ye often shared a book written by his father, titled Iron Cavalry’s Voice. He would take it out and read poems aloud to us. One piece vividly depicted the torrential flooding at Shiguohui in Qingtian, where the river roared and boatmen stood fearless in the face of danger. The poems brought to life the famous landmarks along the Ou River, and recounted real wartime experiences. The collection was filled with energy and detail, chronicling decades of General Ye’s life in the military. He truly embodied the saying: “A general on horseback, a scholar with pen in hand.” The people of Qingtian were truly exceptional.

One day, an elderly woman visited our workshop. She had joined the Communist Party back in the 1930s while studying at university and had long worked as an underground member in Shanghai. Her husband had once served as China’s representative to UNESCO. They were both from Qingtian. She spoke with us in a distinctly Dongyuan-accented Qingtian dialect. It felt like home—when Qingtian people meet, even far from home, there’s an undeniable kinship. That day was no ordinary reunion: a cousin visiting her cousin from the old village. Among Qingtian folks, such familial ties run especially deep.

Not far from our workshop in Paris’s 3rd arrondissement stood Phoenix Bookstore, a Chinese-language bookstore that I visited every weekend without fail. I vividly remember the first time I came across the Newlywed Farewell (Xin Hun Bie) erhu cassette tape there. The melody was adapted from a Tang dynasty poem by Du Fu, recounting the harrowing partings during the An Lushan Rebellion. In that era, even newlyweds were not spared from forced conscription. The poem tells of a young bride tearfully bidding farewell to her husband, now a soldier. “The world shifts in cruel error; I’ll see you no more”—a line so haunting in its finality.

That piece struck a deep chord with me, an immigrant far from home, navigating life in a foreign land. I brought the tape back to the workshop and played it. The first person moved by it was Mr. Xianchao, the workshop owner’s brother-in-law and a former craftsman from the Qingtian Stone Carving Factory. A music lover with few to share his passion, he rushed to Phoenix Bookstore and bought his own copy. The next to be touched was Mr. Ye himself. For him, the sorrow of separation echoed in his own life. After the Chinese Civil War, his father fled to Taiwan while his aging mother remained in mainland China. The family was torn apart, left only with memories and silence. Listening to the music, he could not hold back his tears.

During my free time, I often stayed at Phoenix Bookstore. Sometimes after lunch, I would spend the entire afternoon there, reading until the doors closed for the day. Being surrounded by books gave me a sense of peace—it was, without question, the most comforting way to spend a day. Many Chinese international students saw me there so frequently that they began asking which subject I was studying. I would smile and answer honestly: I work at a garment workshop.

At the end of 1988, my wife arrived in Belgium, thanks once again to the help of my cousin Yang Pengmei, who arranged for her tourist visa. Within the valid period, she received a transit visa from the Austrian Embassy in Belgium. After entering, we sought to legalize her stay through a nominal restaurant investment with relatives. Of course, this arrangement was symbolic—she didn’t actually manage the restaurant or receive any profit. It was simply a way to remain legally. We continued working in Paris.

In August 1990, our second daughter was born at Montreuil Hospital in Paris. Since we didn’t have legal status, we had to pay all the medical expenses out of pocket. I still remember the bill: over 6,000 francs.

In 1991, Spain implemented a labor amnesty—what everyone called “legalization.” That marked the end of our working chapter in Paris. We boarded a train to Madrid, and as it crossed the Seine River, I looked out the window one last time. The Eiffel Tower shimmered in the water’s reflection, swaying slightly in the breeze.

Goodbye, Paris.