From the 1960s to the 1980s, all of Southeast Asia was thrown into chaos, with wars breaking out everywhere.

Wherever there was war, there would inevitably be all kinds of refugees.

The southward migration of Chinese people—what Chinese history calls “going down to Nanyang”—had already been ongoing for hundreds of years.

In the early days, many people who could no longer survive in mainland China fled to Southeast Asia and became what we now call overseas Chinese.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, anti-Chinese movements began to break out across various parts of Southeast Asia,

with Vietnam and Indonesia experiencing the largest-scale incidents and the most severe persecution of overseas Chinese communities.

Large numbers of overseas Chinese were expelled and forced to return to China.

This included not only ethnic Chinese from Vietnam, but also from Indonesia.

Relatively speaking, the Chinese Indonesians suffered even more than the Vietnamese Chinese.

However, as long as Chinese Indonesians were fortunate enough to return to their motherland,

they were all classified as “Returned Overseas Chinese” (归国华侨) and were properly resettled.

They were the first to be granted official household registration (hukou) and Chinese national ID cards, and were given full political rights as citizens.

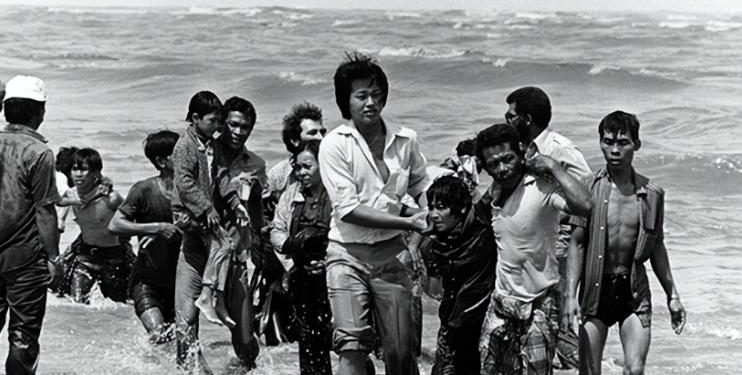

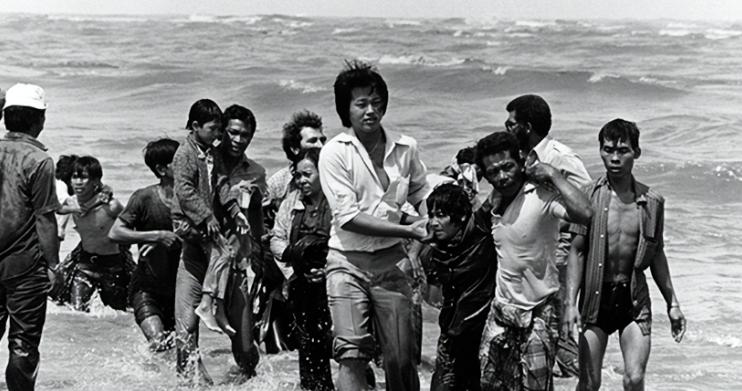

But in the late 1970s, when hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese Chinese returned to the mainland and Hong Kong,

they could only be classified as “refugees.”

During the Vietnam War, many Vietnamese refugees fled to Hong Kong,

where most could only struggle to survive at the very bottom of society,

causing a major headache for the British colonial government at the time.

Even today, many Chinese Hong Kong residents of Vietnamese descent can still be found.

They were once Vietnamese refugees, and most of them still live in the lower rungs of Hong Kong society.

In 1979, after the Sino-Vietnamese War broke out,

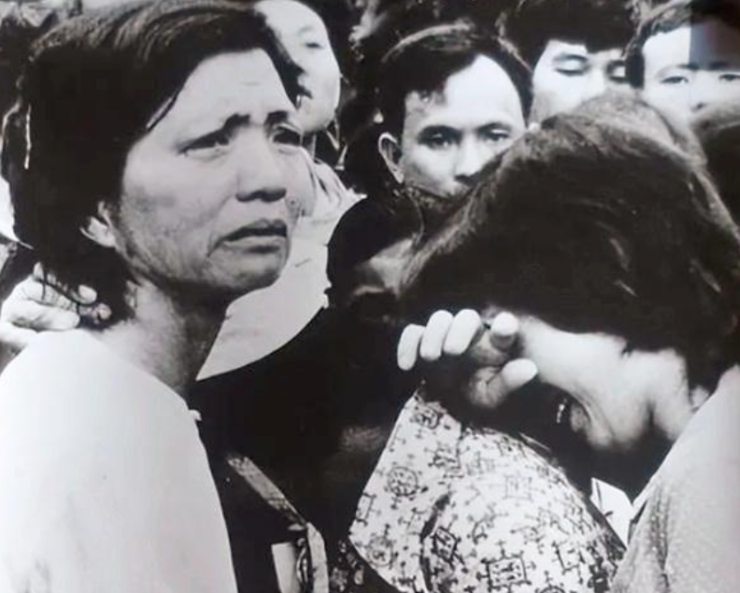

Vietnam’s ruling Le Duan faction began expelling ethnic minorities in northern Vietnam—these were mostly ethnic Chinese.

They were robbed, driven out, and their houses, shops, farmland, cattle, and personal property were all seized.

Left with no means of survival, these ethnic Chinese from northern Vietnam had no choice but to flee to China’s border regions in Yunnan Province and the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

In Dongxing, Guangxi, at a place called Hongshuqiao, a refugee camp was established, housing over a thousand people.

In Jinping County, Yunnan Province, a total of 19 villages were settled by Vietnamese refugees, with the population numbering in the thousands.

As of 2024, many of them still carry the refugee status given to them back in the 1980s, and are still referred to by locals as “Vietnamese refugees.”

However, the local government in Jinping did allocate farmland to these people, allowing them to survive through their own labor.

Today, their standard of living is far higher than that of their relatives who remained in northern Vietnam.

In 1981, instructors and students from the PLA’s Guangzhou Vietnamese Language School frequently visited Vietnamese refugee camps to offer support and assistance.

These individuals were familiar with the terrain and local customs in northern Vietnam and had strong proficiency in both Vietnamese and Chinese.

Our intelligence officers would engage with them in conversation to improve their Vietnamese speaking skills.

Some of these Vietnamese Chinese refugees were even assigned to various military units engaged in the border conflict with Vietnam, serving as interpreters and assisting in the psychological support and education of Vietnamese prisoners of war.

During the decade-long war of attrition along the Sino-Vietnamese border, these Vietnamese Chinese refugees played a significant supporting role.

Compared to them, Chinese Indonesians who returned to China enjoyed far higher social and political status.

Upon their successful repatriation, they were granted full citizenship and no longer faced persecution from anti-Chinese factions in Indonesia.

This preferential treatment was largely due to the contributions made by overseas Chinese in Indonesia—particularly during the War of Resistance Against Japan.

Led by prominent overseas Chinese figures like Tan Kah Kee (Chen Jiageng), many Indonesian Chinese not only donated vast sums of money to support China’s war effort, but also personally assisted with transporting vital supplies.

They drove trucks and carried wartime materials across the Burma Road, directly supporting the anti-Japanese front.

Indonesian Chinese made up the vast majority of these supporters.

Moreover, the persecution of Chinese Indonesians was extreme.

They suffered mass killings and brutal treatment under the Sukarno regime, and by the time they returned to China, their numbers were already very limited.

By the late 1960s, 702 surviving Chinese Indonesians arrived in Fujian on a British-leased cargo ship and were warmly welcomed by crowds lining the streets in Quanzhou.

In contrast, no such scenes of celebration were seen for the returning Vietnamese Chinese refugees.

Most Chinese Indonesians who returned were able to reconnect with relatives in mainland China.

With the help of their kin, they were more easily reintegrated and recognized by society.

The Chinese government also offered favorable treatment and policies to support these returnees.

However, after the reunification of North and South Vietnam in 1975, the Le Duan regime openly expelled over one million ethnic Chinese in an attempt to curry favor with the Soviet Union and gain diplomatic and military support.

In doing so, they looted the properties, shops, and even gold and silver belongings of Chinese Vietnamese residents in the south.

According to statistics, the anti-Chinese campaign in Vietnam forced 1.5 million ethnic Chinese to flee the country.

Taiwan, Guangxi, Yunnan, Hong Kong, Fujian, and Guangdong collectively received more than 290,000 of these refugees.

But because of the overwhelming numbers—and the fact that many native Vietnamese were mixed in with the fleeing crowd—China, constrained by its national strength and international pressure at the time, could not dispatch planes or ships to bring them all back.

With hundreds of thousands of people entering China in a short period, it became extremely difficult to manage.

As a result, they were designated as refugees.

Many of them still lack official Chinese household registration (hukou) even today.

Compared to the Chinese Indonesians, these Vietnamese Chinese returnees were clearly given lower status and fewer protections.