In the early hours of December 3, 1984, in Bhopal, India, 16-year-old Rehana Bi and her family were peacefully asleep, unaware that within hours, their lives would be thrown into irreversible chaos.

Suddenly, a frantic knock shattered the stillness of the night. A neighbor was pounding on their door and shouting, desperately trying to wake the family from their slumber.

When Rehana’s parents opened the door, they were met with a thick, foggy air and a suffocating stench—poisonous gas was descending from the sky, engulfing the unsuspecting neighborhood.

The air was filled with coughing and screaming. Rehana and her family tried to flee the cloud of toxic gas. But in the chaos, with limited visibility and her mother eight months pregnant and barely able to move, the family couldn’t get far. In the end, they collapsed by the roadside.

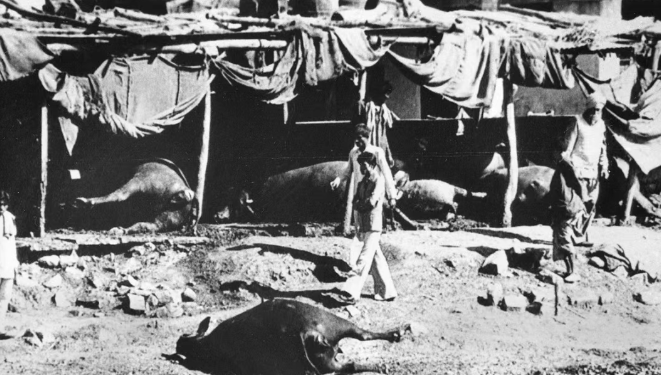

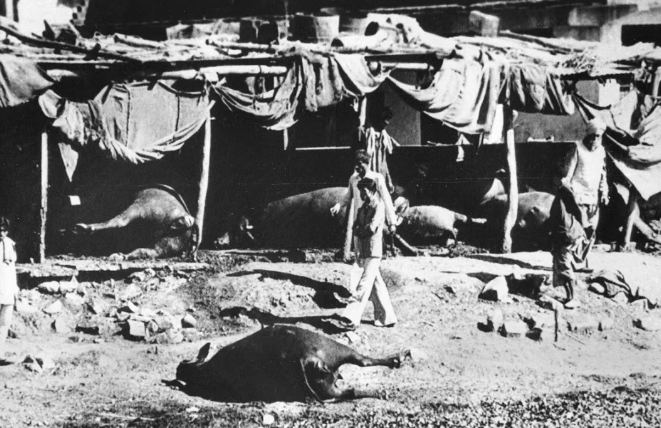

Over 500,000 people were exposed to the poisonous gas cloud, and thousands died on that very day. Rehana’s parents and three-year-old brother were among the victims.

Rehana was one of the survivors. She still remembers that after her mother died, the unborn child in her womb kept moving until the next morning. It wasn’t until then that someone could help wash and bury the bodies.

The Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster is considered one of the worst industrial catastrophes in human history. Nearly 40 years later, the toxic aftermath still lingers, and survivors remain haunted by the nightmare of that night.

In the mid-20th century, globalization and industrialization accelerated, bringing new economic opportunities to low- and middle-income countries. During this period, the Indian government introduced a series of policies aimed at encouraging foreign companies to invest in local industries.

The Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), a U.S.-based industrial giant, operated across various sectors including petrochemicals, mining, and consumer electronics. It was also among the first American companies to invest in India. In 1934, its subsidiary, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL), was established. UCC held a majority stake, while the Indian government owned 22%, with the remaining shares held by financial institutions and private investors.

At its peak, UCIL generated nearly $200 million in annual sales, employed approximately 9,000 workers, and operated 14 factories across India. The Bhopal plant was one of them.

India, with its vast population, had a high demand for food, and successive outbreaks of pests led to a surge in the need for pesticides and fertilizers. From its inception, the Bhopal plant primarily focused on producing carbamate-based pesticides.

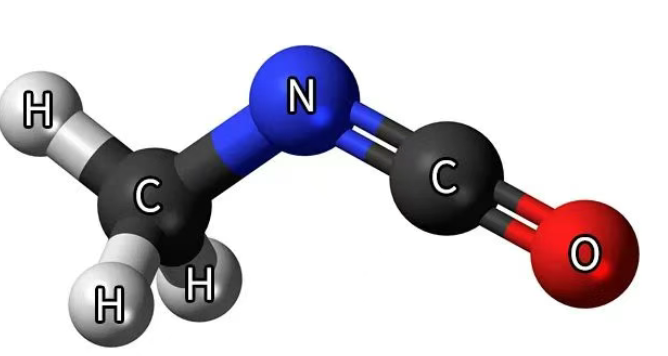

During the manufacturing process, the plant required a highly toxic chemical ingredient: methyl isocyanate (MIC). This substance is a colorless liquid at room temperature with a pungent odor and is extremely volatile, reaching its boiling point at just 39°C (102°F).

MIC was the very chemical that leaked during the Bhopal gas disaster.

MIC is highly lethal and poses severe risks to the eyes, respiratory system, digestive tract, and skin. Inhalation can cause coughing, breathing difficulties, and pulmonary edema; skin contact may result in redness, pain, and a burning sensation; eye exposure may lead to pain, redness, and even blindness. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has emphasized that MIC should be stored in sealed containers and must never be allowed to enter the environment.

In 1984, the year UCIL was celebrating its 50th anniversary, tragedy struck. Between midnight on December 2nd and the early hours of December 3rd, a deafening roar echoed from the Bhopal plant. Approximately 40 tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC) were released from the storage tank as high-temperature gas and then leaked out of the factory.

The plant workers were the first to be hit. The control room was quickly engulfed in toxic fumes. Over a hundred night-shift employees scrambled for oxygen masks and tanks, shouting “Leak! Leak!” in panic as they desperately tried to escape upwind. The situation was already out of control. All they could do was watch helplessly as the gas spewed out, forming a dense, deadly white cloud that drifted above the plant and flowed beyond its walls.

Outside the factory walls lay the heart of old Bhopal — bustling by day with lively open-air markets, street vendors calling out from pushcarts and stalls, and children playing in dusty alleyways. By night, it was supposed to be calm and peaceful, with families asleep, awaiting the dawn of a new day.

But on that cool night, the poisonous gas swept silently through temples, streets, lakes, and shantytowns, gradually spreading and suffocating the unsuspecting people of Bhopal in their sleep. At the time, gas concentrations in the city exceeded safety limits by over a thousand times.

The sudden disaster placed immense pressure on the local healthcare system. Hamidia Hospital, the largest medical facility in Bhopal at the time, was quickly overwhelmed. Within hours, long lines had formed, and more patients kept arriving. Other major hospitals in the city faced similar conditions—streams of victims were brought in, coughing, rubbing their burning eyes in agony, or too weak to move.

The hospitals were overcrowded, with shortages of medical staff and beds. Making matters worse, the incident had occurred without warning, and initially, doctors had no idea what kind of gas people had been exposed to. As a result, many patients did not receive timely or appropriate treatment.

Twelve hours after the incident, executives at the parent company in the United States received the first report about the disaster. Soon, the tragedy became front-page news around the world.

To this day, the exact number of people who died from the gas leak on that day—and the total death toll in the weeks and years following—remains a matter of dispute. Estimates suggest that between 2,000 and 4,000 people died immediately, most of them residents of slums near the plant. Because MIC is heavier than air and tends to flow close to the ground, young children were particularly vulnerable. In the weeks after the incident, the death toll rose to an estimated 7,000 to 10,000. In total, over 500,000 people were exposed to the toxic gas, and at least 100,000 suffered injuries.

After the disaster, the Indian government, Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), and various international organizations each dispatched investigative teams to probe the cause of the gas leak. Through examining records and documents, interviewing employees, and collecting field samples, different investigation groups tried to piece together the events of that fateful night—like assembling a puzzle.

All clues pointed to one thing: water.

MIC reacts exothermically with many substances—especially water. On the night of December 2, 1984, a large volume of water entered Tank 610, which stored over 40 tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC). The reaction released increasing amounts of heat, raising the tank’s temperature rapidly. The cooling system, which should have prevented overheating, had been disabled, and the high-temperature alarm system failed as well. In the early hours of December 3, a thermal runaway reaction occurred, tank pressure spiked, and Tank 610 ruptured—releasing over 40 tons of superheated toxic gas.

With such a deadly substance, the plant should have had multiple layers of safety systems to prevent a leak. Why did they all fail? What exactly went wrong inside the plant?

Deeper investigations revealed a chain of complex, interrelated events.

First, the plant’s location was flawed.

A highly populated urban area is not an appropriate site for a chemical plant, yet the Bhopal factory stood next to a densely populated slum. Furthermore, the amount of MIC stored at the facility kept increasing. Initially, the plant imported small quantities of MIC from the parent company. But in an effort to be more competitive, Bhopal began producing MIC locally—leading to larger on-site inventories.

As risks rose, the plant cut costs and staff.

In the 1980s, India suffered severe droughts, failed crops, and widespread famine. Farmers went into debt, cutting back on pesticide purchases. As profits declined, the plant’s golden days ended. Cost-saving measures led to mass layoffs: the number of operators was halved from 12 to 6, and maintenance teams were slashed from 6 to just 2. Training periods were shortened from six months to a few weeks—or even days. Many workers underestimated MIC’s toxicity, knowing it was “dangerous,” but unaware it was lethal in even small amounts.

Worse still, the plant implemented several “non-standard operations,” repeatedly modifying the tank’s intended design—at least four times.

Originally, MIC tanks were connected to a transfer pump and a circulation pump. The transfer pump pushed MIC to the production line, while the circulation pump kept MIC cool, reducing the chance of thermal runaway.

But MIC is highly volatile, and both pumps frequently leaked. Leak detection didn’t rely on manuals or equipment—but on the workers’ physical senses. As one employee told The New York Times, “We were human leak detectors.” If their eyes began to sting or water, they would locate the leak and fix it.

Since the transfer pump leaked often, the plant decided to stop using it. Instead, they repurposed a return line (normally used for unused MIC to flow back into the tank) to transport MIC to the production line. By injecting nitrogen into the tank, they increased internal pressure from 1.3 atm to over 9.4 atm—sometimes as high as 16.8 atm—forcing MIC to flow outward.

This nitrogen was originally meant to protect the pipes from corrosion. In a cost-cutting move, the plant had replaced stainless steel pipes (resistant to rust) with cheaper carbon steel, which rusts easily. Rust can react with MIC, creating precipitates that clog pipes. To prevent clogs, nitrogen needed to flow continuously through the pipes. But by rerouting nitrogen to pressurize the tank, its protective effect was lost—and rust and blockages returned.

To deal with the clogged pipes, the plant made a second “non-standard move”: they flushed the pipes with water—introducing water dangerously close to the MIC tanks.

This wasn’t the end of the shortcuts.

Although the transfer pump was abandoned, the circulation pump—which cooled the MIC—was still crucial. Yet the plant shut it down too. On January 9, 1982, a leak in the circulation pump injured 25 workers. The response? The cooling system was shut off permanently, and the refrigerant repurposed for other uses—eliminating cooling and saving money. That was the third “non-standard operation.”

Originally, the high-temperature alarm for the MIC tanks was set at 11°C. With the cooling system gone, the MIC temperature rose to 15–40°C. Daily alarms became routine. To avoid the nuisance, the plant disabled the alarm system—a fourth non-standard change.

These changes seemed to “solve” problems in the short term—but the risk quietly grew.

On the night of the disaster, around 11:00 PM, operators noticed a fivefold increase in tank pressure within 30 minutes. But they assumed this was normal: “Pressure and temperature readings were often unstable,” they said. “The instruments are probably faulty.”

By 11:30 PM, workers’ eyes were burning—“human leak detectors” had sensed trouble. The supervisor assumed it was a minor leak and said they would check after the tea break.

Tea break ended around 12:40 AM. Minutes later, panic erupted.

Temperature and pressure gauges exceeded maximum limits. The concrete slab above the tank began shaking. One worker recalled, “There was a terrible sound, like a giant pot boiling. The whole floor was vibrating. It was like a blast furnace.” As he ran, he turned back and saw cracks forming in the 15 cm thick concrete slab. A loud hiss followed—and then the gas erupted.

As for how the water got into the tank, two theories remain.

The first and earliest theory is the “water-wash accident.” Pipes were blocked, and workers flushed them with water, as usual. But due to valve failure or human error, the wash water entered the MIC tank, triggering the disaster. The Indian government supports this theory, blaming poor maintenance, management failure, and safety negligence.

The second theory is sabotage. UCC claimed that a disgruntled employee had directly connected a water hose to the tank, possibly during a shift change. They argued the water-wash theory originated from media speculation and noted technical inconsistencies, such as insufficient water pressure to reach the tank.

UCC was accused of scapegoating employees to deflect responsibility. Both sides accused each other of altering logs, tampering with testimonies, and hiding evidence. To this day, the truth remains unclear—leaving the question of ultimate responsibility unresolved.

Due to the multinational nature of the company involved and the numerous stakeholders implicated, what began as a straightforward industrial accident gradually evolved into a complex event involving legal, political, and economic dimensions.

After the disaster, Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) attempted to distance itself from responsibility, claiming that the Bhopal plant was entirely constructed and operated by its Indian subsidiary. At the time, Jackson B. Browning—head of UCC’s Health, Safety, and Environment programs and one of the company’s chief spokesmen during the crisis—stated in a report that some politicians and writers may have exaggerated the death toll for political or dramatic effect. He noted that many people seen in TV disaster footage had bandages covering their eyes, giving the impression that widespread blindness had occurred, whereas, in reality, only a small number of people had suffered permanent eye damage.

Browning added: “Regardless of our contributions to India’s industrial goals, the current political debate casts us as a typical multinational villain, exploiting India’s people and resources.”

Caught in the whirlwind of conflicting narratives, the deaths of victims marked only the beginning. For the survivors, a different kind of suffering began. As survivor Rashida Bi put it: “Those who died in their sleep on the night of December 2, 1984, were the lucky ones. Those who survived have been dying slowly every day. We are treated as if we were the culprits.”

For years, survivors have been fighting for compensation, medical care, and environmental cleanup.

In 1985, the Indian government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act. Under this law, the government was authorized to represent all victims—both domestically and internationally—and act as their sole legal representative in seeking compensation.

That March, the Indian government filed a lawsuit in the United States against UCC and UCIL. However, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York stalled the proceedings. After more than a year of deadlock, the court dismissed the case, citing forum non conveniens—claiming the disaster occurred in India and should be tried there.

Consequently, the Indian government turned to the District Court in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. In February 1989, under the mediation of the Indian Supreme Court, a settlement was reached: UCC and UCIL agreed to pay $470 million as a full and final settlement.

The $470 million figure was based on disputed data—3,000 deaths and 100,000 injuries. Ten days after the ruling, UCC paid $425 million to the Indian government, and UCIL paid $45 million.

Many saw this amount as grossly inadequate. From 1963 to 1985, UCC had mined and sold asbestos—a known carcinogen that also causes lung fibrosis and pleural effusion. The company faced numerous lawsuits from asbestos victims. For instance, after Willis Edenfield died of mesothelioma (a cancer affecting the chest and abdominal linings) due to exposure while working in and around a UCC asbestos plant, his widow sued for wrongful death and won a $2.38 million settlement.

If the Bhopal victims had received compensation on par with asbestos claimants, UCC would have been liable for $10 billion—an amount greater than its own valuation and insurance coverage at the time.

Victims rejected the $470 million settlement as insufficient to cover their suffering and losses, but the judgment stood. The compensation process itself was complex and prolonged. The first payments—totaling approximately $145 million—weren’t disbursed until 1995, nearly ten years after the disaster. The remaining $325 million sat in government accounts accruing interest until 2004, when additional disbursements finally began.