Wuxia fiction has always been a river of contending currents.

At the forefront are Jin Yong, Gu Long, Liang Yusheng, and Wen Ruian. Beyond them, countless other names fill the world of swords and ink.

In Chinese history after the Qin dynasty, whenever the land was divided among competing dynasties, the question of “legitimacy” would inevitably arise in the eyes of historians.

After all, there can only be one Son of Heaven at any given time.

Among all the writers of wuxia fiction, Jin Yong and Gu Long stand peerless, soaring far beyond the rest. They represent two entirely different styles—Gu Long’s unrestrained flair and poetic rhythm often tug at my heart more deeply.

Yet, when it comes to declaring the orthodoxy of the genre, there is no doubt: there is only one Jin Yong.

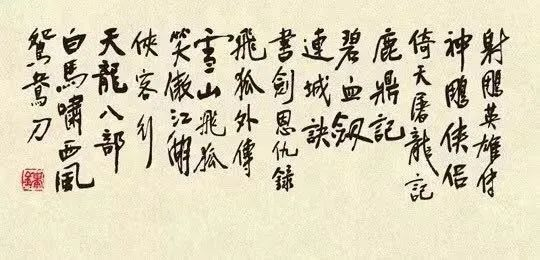

“Flying snow shoots the white deer through the skies, laughing books of gallant heroes lean on jade love.”

Today marks the 100th birthday of Mr. Jin Yong. Time flows swiftly, but the spirit of chivalry remains. This piece is written in honor of the master.

The world of wuxia is such a world: everyone is a martial arts master, all defying law and order; one wrong word, and blades are drawn, blood is spilled.

There are no ordinary people, no rules of real society, and rarely any mention of how one earns a living.

The common folk who toil from dawn to dusk for food and shelter either have no names or die the moment they appear with a scream. The entire stage belongs to the “superhumans” who never truly existed.

Thus, this is a world built on illusion. Between people, there is only one kind of relationship—grudge and revenge in the jianghu.

Based on such a foundation, no matter how the stories are arranged, they inevitably come across as painfully dull. And this—this is precisely the impression held by those who don’t read wuxia novels and vehemently oppose them.

In a field overgrown with wild weeds, it’s no surprise that some would cling to such stereotypes. Of course, no matter how poor a wuxia novel might be, it’s rarely as mindless as the stereotype suggests.

There is still right and wrong, good and evil, heroes and villains, justice and injustice.

But for the majority of wuxia novels, that’s about as far as they go.

True masters are different. Those with profound internal strength can leave footprints on stone slabs.

Jin Yong and Gu Long are such masters. With their bare hands, they lifted wuxia fiction from being lowbrow pulp into the halls of literature.

Especially Jin Yong—he is the sage among them.

How did he manage to do it? To put it simply: Even a knight-errant follows a code.

If the phrase “even a thief follows a code” shocks us with its irony, then “even a knight-errant follows a code” seems like a given—doesn’t it?

But if the “code” merely refers to the battle between good and evil, that’s far too simplistic. The meaning of dao—the “Way”—has never been that one-dimensional.

Jin Yong approached storytelling not just as a writer, but as a deeply learned scholar. He planted his fantastical tales firmly in the soil of Chinese traditional culture.

He blended Confucian self-sacrifice, Daoist freedom, Buddhist aestheticism, Legalist rule of law, and Mohist chivalry—fusing them into a parallel universe both complete and coherent, both real and unreal.

It is a self-contained world. One that explains everything through its own rules.

Just like C.S. Lewis created Narnia, and Tolkien crafted The Lord of the Rings, the genius lies not only in imagination—but in the creation of a self-sufficient system. Within it, no matter how fantastical, readers lose themselves without ever questioning its truth.

In my view, Jin Yong’s achievements surpass even Lewis or Tolkien. Because for the vast Chinese-speaking world, Jin Yong carried a cultural mission:

He picked up the shattered fragments of traditional Chinese culture—scattered by the march of modernization—and pieced them back together with the glue of gripping narrative.

Thanks to him, Chinese people around the world could find understanding and shared identity through his bridge.

“Even a knight-errant follows a code”—and that code is none other than traditional Chinese culture.

Outside of Jin Yong, no other martial arts novelist has either the capability or the intention to shoulder such a serious mission.

Most others were content to see their works sold on street stalls, stacked next to pulp fiction and erotic literature.

This is the distance between a hero and the mundane.

In Jin Yong’s martial arts universe, there exists a spirit.

This spirit originates from the mainstream philosophies of Chinese tradition—Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, Mohism, and Legalism—each reflected in turn.

This spirit is carried by characters. The deepest ideals within each of these schools of thought are infused into the souls of his characters, becoming their inner creed.

As for the protagonists, they often embody all of these philosophies in harmony—blended into a cohesive whole.

The individual and the nation, the personal and the political, find both tension and unity within this structure.

Thus, love becomes obsession, hatred becomes madness, compassion and nature and law—all take on weight and meaning under such a grand, sweeping backdrop.

Every reader feels that the actions of the protagonist are, in essence, their own.

He fights the battles they wish they could fight. He upholds the values they secretly long to defend.

That vast and sweeping backdrop is called the jianghu.

All martial arts novels and gangster films refer to their world as jianghu.

Yet Jin Yong’s jianghu is not a realm of fantastical mountains and immortal realms.

Nor is it the blood-soaked alleyways of Young and Dangerous films, filled with gleaming machetes.

His jianghu is the convergence of all schools of thought;

its idols are not gods, not even Lord Guan,

but rather the soul of the Chinese people—past and present.

Jin Yong’s jianghu does not exist in reality, yet it never departs from the heart.

It is not tangible, but never questioned.

In this sense, jianghu is a creation of Jin Yong himself.

As much as I admire Gu Long’s famous line,

“In the jianghu, a man is not his own master,”

when it comes to the true lineage of jianghu, it still belongs to Jin Yong.

As far as I know, China has three jianghus.

One belongs to Zhuangzi.

“Better than moisten each other with spit is to forget each other in the rivers and lakes.”

(Xiang ru yi mo, buru xiang wang yu jianghu.)

That is a vast and boundless place—capable of holding giant fish and soaring birds.

It represents an ideal realm of freedom and natural being.

Another is Confucian.

“When dwelling in the halls of power, worry for the people;

when living far in the rivers and lakes, worry for the ruler.”

(Ju miao tang zhi gao ze you qi min, chu jianghu zhi yuan ze you qi jun.)

There, jianghu refers to the folk world—to the common people.

And the last jianghu belongs to Jin Yong.

This is also the one most familiar to Chinese people.

Once it appears, the golden wind rises and sweeps across the land.

Song, Liao, Western Xia, Jurchen, Mongols, Tibetans, Dali—

banners fluttering, spirits soaring.

Because it is Jin Yong who created this jianghu,

he thus possessed the authority to set its standard.

What defines a true xia—a hero?

Not merely generosity and helping the weak.

Not just blood oaths, shared life and death, loyalty that reaches the skies.

Not only righteous indignation and leaping to action at the sight of injustice.

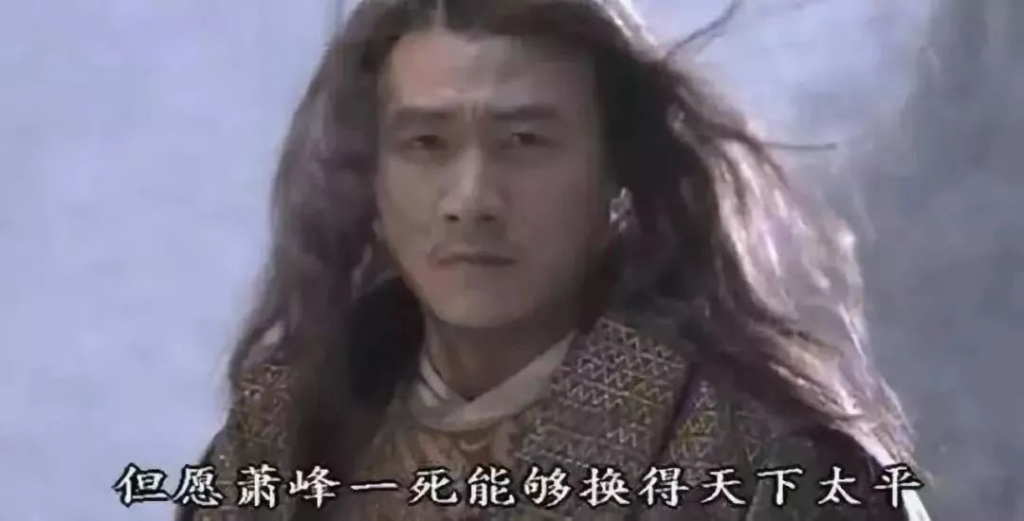

He once said:“The greater xia serves the nation and its peoplethe lesser xia serves friends and neighbors.”

This built upon the Mo-ist foundation of xia—a spirit of universal love and justice—

while incorporating Confucian ideals, endowing the xia with a loftier value system.

Such a grand vision of xia exists, so far, only in the jianghu Jin Yong created.

If one were to ask:

Who best embodies “Chineseness” in contemporary Chinese literature?

The answer must be: Jin Yong.