Xu Haifeng was born in Zhangzhou, Fujian Province.

At the age of 15,

he and his family settled in Xinqiao Town, Hexian County.

Xu Haifeng was an outstanding student.

In high school,

his physics teacher was especially fond of him,

and upon graduation,

hoped he would stay in town

to work in radio repair.

But Xu politely declined.

He was determined to enlist in the military—

His true dream

was to become a soldier,

just like his father.

Xu Haifeng was no stranger to guns.

Especially when it came to shooting,

he already had considerable experience.

Because his father was a soldier,

Xu had access to firearms from a young age,

and developed a deep fascination with them.

Children weren’t allowed to play with real guns,

but they always found substitutes.

For Xu, it was the slingshot.

Even at a young age,

his aim was deadly accurate.

He could hit over 200 sparrows in a single evening—

earning him the local nickname “King of the Slingshot.”

After graduating high school,

Xu Haifeng acquired an air rifle.

At the time, living standards were generally low,

especially in rural areas,

where money was tight.

Ammunition was scarce,

so to save money,

his family helped him collect used toothpaste tubes—

which were made of lead back then.

They would melt the tubes down in a pot,

and recast them into pellets

so Xu could continue his target practice.

after graduating from high school,

Xu Haifeng applied to enlist in the military.

However, he was still eight months under the required age,

so his application was not approved.

Due to a series of subsequent reasons,

he missed the chance to join the army

and instead began his life as a “sent-down youth.”

From a young age,

Xu Haifeng had always been someone who loved to tinker and figure things out.

When he saw a classmate’s father repairing shoes,

he went and bought an awl of his own.

Soon, he was the one who repaired all his family’s shoes.

Being proficient in radio electronics,

he often helped his neighbors repair household appliances.

He also had a passion for Chinese herbal medicine,

read extensively on the topic,

and for a time, worked as a barefoot doctor.

He even assisted with Party member education programs in the town.

Xu Haifeng firmly believed that

as long as one is serious and dedicated, there is no task that cannot be accomplished.

Because of this spirit,

he earned a nickname in the village: “Master of Seventy-Three Trades.”

It meant that he was skilled in every trade imaginable—and even more than most.

In 1979,

Xu Haifeng was recruited for a civilian job and returned to the city.

He joined the Xinqiao District Supply and Marketing Cooperative in Hexian County

and became a fertilizer salesman.

The ammonia in fertilizer

was extremely irritating to the eyes.

Prolonged exposure often led to eye inflammation,

and over time,

his vision deteriorated rapidly as a result.

While working at the Supply and Marketing Cooperative,

Xu Haifeng never forgot his passion for shooting.

One day, by pure chance,

he heard that the local region

was in the process of forming a shooting team

to participate in the 5th Anhui Provincial Games.

Even more coincidentally,

the coach of this shooting team

was none other than his former physical education teacher from middle school.

Xu Haifeng reached out to his former teacher

and expressed his strong desire to join the team.

After going through a selection process,

Xu Haifeng was successfully accepted into the team

and officially began his journey in professional shooting.

une 5, 1982

This day marked a significant turning point in Xu Haifeng’s life.

From this day onward,

Xu Haifeng began participating in the intensive shooting training

organized by the Chao Lake Regional Sports Committee of Anhui Province.

In just two short months,

he won the shooting championship at the Anhui Provincial Games,

and effortlessly broke the provincial record.

It was from this moment on

that people started calling him a “shooting prodigy.”

Thanks to this achievement,

Xu Haifeng was officially selected into the Anhui Provincial Shooting Team,

marking the beginning of an entirely new chapter in his life.

Back then, training conditions in China were extremely tough.

In the entire Anhui Provincial Shooting Team,

there were only two imported pistols,

and only the athletes selected for competitions had the chance to use them.

Imported bullets were even more scarce,

each shooter received a strictly limited quota.

Moreover, the training grounds of the provincial team had no heating in winter.

Since shooting required athletes to keep their hands exposed for long periods,

Xu Haifeng developed severe frostbite.

In March 1983,

at the East China Invitational Competition,

Xu Haifeng represented the Anhui shooting team,

won two shooting gold medals,

and broke the national record.

By the end of that year,

he was transferred to the national team,

joining veteran shooters like Wang Yifu as teammates.

At that point,

there was less than one year left until the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Most people would never guess—

the sharpshooter Xu Haifeng actually had poor eyesight.

His vision was uneven,

1.5 in the left eye and only 0.5 in the right—

but shooting requires right-eye aiming.

Before his physical examination for the national team,

Xu Haifeng secretly memorized the last line of the eye chart.

Unexpectedly,

he managed to successfully pass the test and slip through.

Can you really see the target with 0.5 vision?”

This is a question that Xu Haifeng, who later became a world champion,

has been asked more than once.

His explanation was simple:

“Actually, for pistol shooters, 0.5 vision is sufficient.”

Rifle shooters have slightly higher visual requirements,

but in shooting, one of the most crucial techniques

is being able to clearly see the front sight and rear notch.

Even if a person with poor eyesight

can only clearly see objects within one meter,

they can fully focus on the sights,

so there’s less room for major errors in key technical movements.

As a result, the deviation on the final target

might actually be smaller.

He added,

“We used to run experiments.

Athletes with 1.5 vision or better

had to wear special glasses with 0.5 diopters

to intentionally blur the target.”

Besides aiming,

arm stability is also vital for a shooter.

Xu Haifeng trained intensively and consistently

in finger strength, arm strength, and wrist control.

Here, his years of physical labor in the countryside

became a major asset.

Those hard days made him tough and resilient.

As an athlete,

he always spent the longest time practicing aiming.

He could remain as calm as still water

during the tedious and repetitive professional training sessions.

Xu Haifeng said,

“Anyone can aim.

The key lies in how you pull the trigger.

I studied the relationship

between trigger pull and the slight movements of the pistol.

Eventually, I nailed it.

My trigger technique is very unique—

when the gun sways over the 10-ring zone,

I pull the trigger, and it hits the 10.

It’s just that simple.”

During national team training,

each week,

the athletes’ performance

was meticulously recorded and compared.

When Xu Haifeng first joined the training team,

his score for 50 test shots was:

20 in the 10-ring,

22 in the 9-ring,

8 in the 8-ring.

Just over a month later,

his stats had improved to:

32 in the 10-ring,

18 in the 9-ring,

0 in the 8-ring.

His progress was astounding.

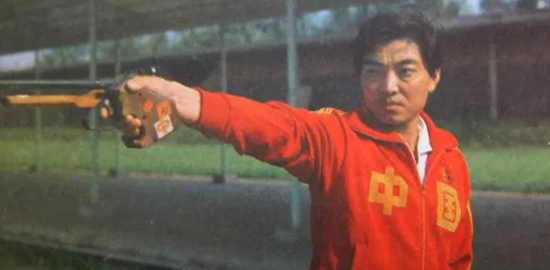

July 29, 1984—

the first day of the Los Angeles Olympic Games.

At 9 a.m.,

the men’s 60-shot pistol slow-fire event officially began.

Competitors from various countries and regions around the world

lined up across 80 shooting positions.

That day,

Xu Haifeng, wearing a red tracksuit,

stood calmly at position No. 40.

At the time,

much of the audience’s attention was focused on

Swedish veteran Ragnar Skanåker,

the gold medalist of the 20th Olympic Games in pistol slow fire.

As the competition began,

Xu Haifeng maintained consistent performance,

scoring 97 rings in both of his first two series.

With his steady showing,

many journalists at the scene

began shifting their focus toward position No. 40.

They opened their program booklets

and discovered the athlete from China—

his name was Xu Haifeng.

The spectators, too,

started to gather behind position 40,

drawn by his calm demeanor and promising performance.

But during the eighth shot of the third round,

Xu Haifeng unexpectedly scored an 8-ring,

causing a wave of nervous tension.

Sensing something was off,

he took a break and sat on the steps near the entrance to collect himself.

At that moment,

whether it was the journalists inside the venue

or the spectators in the stands,

everyone seemed more anxious than Xu himself,

eagerly anticipating

the final outcome of the match.

After some mental readjustment,

Xu Haifeng fired his final three shots with exceptional calm:

10 rings, 9 rings, and 9 rings.

When the final score was tallied—566 rings,

he had edged out Ragnar Skanåker by just one ring

to claim the gold medal.

Upon hearing the news,

then President of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch,

rushed to the shooting venue

to personally present the gold medal to Xu.

Overwhelmed with emotion, he declared:

“Today is a great day in the history of Chinese sports.

It is my honor to personally award this gold medal to a Chinese athlete.”

This was the first Olympic gold medal ever won by China,

a monumental breakthrough

in the nation’s journey on the global stage of competitive sports.

Over the next ten years,

Xu Haifeng would go on to dominate the world of shooting,

winning 13 world championships,

over 30 Asian titles,

and even breaking two world records.