Since the 1980s, the most popular way for American civilians to pursue the American Dream and realize personal success has been through buying a home with a mortgage.

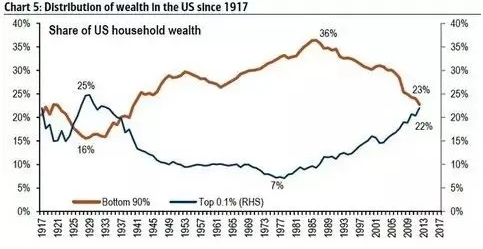

At the time, after President Reagan took office, he implemented a radical neoliberal economic policy characterized by aggressive privatization and extreme market liberalization, which led to a rapid expansion of the wealth gap in the United States.

As the gap between the rich and poor widened, ordinary people—driven by a fear of falling behind socially—began imitating the consumption patterns of the wealthy. And the wealthy were buying property to share in the prosperity brought by neoliberalism.

This gave rise to a nationwide mentality of homeownership and a collective belief that real estate prices would only go up. Those who already owned property naturally hoped for price increases, while those who didn’t yet own homes believed they too could soon “get on the property ladder” and also welcomed rising prices.

Confronted with the social problems caused by increasing inequality and soaring housing prices, the U.S. government was reluctant to reform the tax system to raise capital gains taxes, for fear of offending the wealthy. On the other hand, they found reforming education to help lift poor families out of poverty to be too slow and exhausting.

So instead of choosing to lower housing prices or increase civilian income, they opted for a third path: encouraging ordinary Americans to buy homes on credit. This approach allowed the working class to own property and fulfill the “American Dream,” easing social discontent, while at the same time driving up property values, which pleased the wealthy.

To encourage mass borrowing for home purchases, the U.S. significantly lowered down payment and lending thresholds. Down payments could be zero, and mortgage requirements became so lax that some people were reportedly approved for home loans using their pets’ names.

Two American companies invented a financial product called Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), and here’s how it works:

-

For example, a bank lends a homebuyer $1 million with a 10-year term. The total repayment over the term would be $1.5 million, including interest.

-

The bank then sells the right to this loan to one of the two companies for $1.2 million. These companies either collect the loan repayments themselves or repackage and sell the debt to other financial institutions.

This way, the companies earn a $300,000 profit margin, while the bank quickly recovers its funds and can issue more loans.

These two companies are known as Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation), collectively referred to as the “GSEs” or “the two housing giants.”

This setup appears to benefit both the banks and the GSEs, but it significantly increases overall leverage in the financial system and introduces serious risk. What gave them the confidence to operate this way was the fact that both companies were government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). U.S. Presidents like Bill Clinton and George W. Bush pushed for these agencies to support low-income families in buying homes in the name of “homeownership for all.”

However, loans to these families carried high default risks and were categorized as subprime loans.

In reality, banks and financial institutions also welcomed subprime loans because they carried higher interest rates. As for the increased risk of default? That wasn’t much of a concern—if a borrower defaulted, the lender could simply seize the home. And with property values soaring, reselling the home could often cover the outstanding principal and interest.

But rising home prices depend on rising household incomes. When large segments of the population can only afford subprime loans due to low incomes, property prices become unsustainable in the long run.

By 2007, U.S. housing prices peaked and then started to decline.

Because of low down payments, loose lending standards, and MBS that magnified leverage across the board, even a slight drop in housing prices caused MBS values to plummet, leading to huge losses for financial institutions and severe cash flow issues for individuals and businesses alike.

This cash flow shortage, in turn, triggered further declines in housing prices, creating a vicious cycle that spiraled into a full-blown economic crisis.

This was the global subprime mortgage crisis. And economic crises are never fair — they hurt the poor far more than the rich.

If someone bought a home outright for $1 million and the property value dropped to $800,000, they still owned an asset worth $800,000.

If someone put down a $300,000 down payment and took out a mortgage for a $1 million home, a price drop to $800,000 would leave them with just $100,000 in equity.

But if someone bought a $1 million home with zero down payment, their asset would effectively drop to negative $200,000. (Although in the U.S., once the house is foreclosed, the debt is cleared — so in reality, the asset becomes zero, not negative.)

From 2007 to 2010, the net worth of the poorest 20% of Americans fell from an average of $30,000 to almost zero. Meanwhile, the wealthiest 20% saw their net worth decline by less than 10%, from an average of $3.2 million to $2.9 million.

Even worse, when the housing market rebounded after the crisis, the wealthy recovered and even grew their wealth. The top 10% saw their real wealth (adjusted for inflation) increase by 16% compared to pre-crisis levels.

But the poor? Their homes had already been foreclosed, used as collateral in the crisis. They missed out entirely on the recovery.

The bottom 50% of income earners saw their real net worth cut in half, falling back to 1971 levels. Forty years of accumulated wealth among working-class Americans was wiped out overnight.

Faced with rising home prices and growing inequality, the U.S. government chose not to redistribute wealth or lower housing costs, but instead encouraged borrowing to delay the inevitable.

That delay, however, ended in disaster — triggering a crisis that stripped away decades of middle-class savings.

“The people of the Qin dynasty had no time to mourn themselves, so the generations after mourned for them.