In 1959, Wang Jinxi, a model worker on China’s petroleum front, traveled from Yumen to Beijing to attend the National Heroes’ Conference. During a break in the meeting, he visited the Ten Great Buildings of the capital. While walking down Shatan Street, he noticed that all the passing public buses were carrying large “bundles” strapped to their roofs. Curious, he inquired and found out that these bundles were coal gas tanks. Due to the severe national oil shortage, buses had to rely on coal gas as fuel.

Upon hearing this, Wang felt an overwhelming sense of shame. To him, this was not only a national embarrassment—it was an insult to oil workers, and even more so, a disgrace to himself as a drilling team leader. Tears silently welled up in his eyes and streamed down his face. It was during this very conference that Wang learned of a major oil discovery in the Songliao Basin. Soon after, an unprecedented national oil development campaign erupted in Daqing.

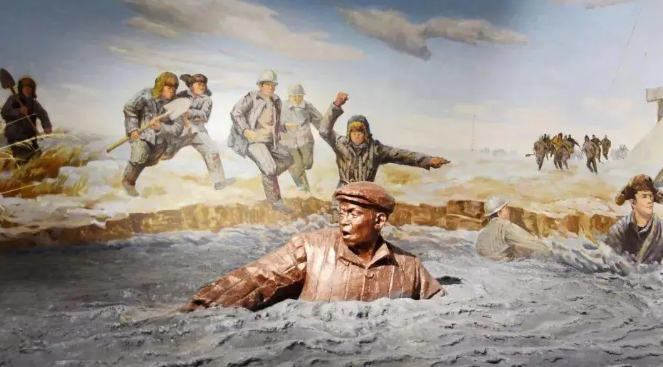

On March 15, 1960, Wang Jinxi led a 37-member drilling team, Team 1205, from Yumen in Gansu Province to Sartu in Daqing, a frigid and remote area. The Daqing oil campaign took place in a time of scarcity, in a place of hardship, under extremely difficult conditions. Facing formidable obstacles, Wang led his workers to confront the challenges head-on.

When the drilling rig arrived, there were not enough cranes to unload the equipment—how could they possibly move dozens of tons off the truck? They resorted to using ropes, crowbars, and wooden blocks, inch by inch, foot by foot, to move the 60-ton rig into position. Piece by piece, they hoisted the diesel engines, gearboxes, and winches onto the platform. After three days and nights of tireless labor, the derrick finally stood on the site.

Just as they were ready to begin drilling, they realized the water pipelines hadn’t been connected, and there were no water tankers available. Where could they get water? To save time, Wang raised his arm and called out to the workers. He led them to a nearby pond where they broke through the ice and carried back water—bucket by bucket, basin by basin—hauling 50 tons to ensure drilling could begin. Wang poured every ounce of his energy into fulfilling his mission: to provide oil for the nation.

Wang Jinxi, known as “Iron Man,” carried with him three treasured items: a copy of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong, a cloth bag of roasted flour (a simple food mixture), and an old sheepskin coat. Born into a poor peasant family, he never had the chance to attend school, but he possessed an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. No matter how busy his days were or how late he went to bed, he always rose early to read Mao’s Selected Works alone among the rubble near the camp. After joining the command post, he took a mentor and studied alongside him at night. After reading, they would discuss the passages and share their interpretations.

Wang didn’t read Mao’s works merely to recite them, but to solve problems, assist comrades, and transform himself. Guided by Mao’s theory of practice, he experimented repeatedly and eventually developed a complete method for overcoming drilling jams, achieving the first nearly vertical well with a deviation of only a little over two degrees—the best in the entire region.

His ability to continue progressing stemmed from his honest approach to mistakes and shortcomings. His team had once drilled a failed well. Every year, he would visit that site, and whenever new workers joined, he would take them there to learn from the failure.

In 1961, although his leg had not yet healed from an injury, Wang was appointed brigade leader. Worried about leading the team astray, he spent his days running between drilling teams, sometimes visiting seven or eight in one day. Life was extremely difficult—food was rationed. He had his family prepare roasted soybean and corn flour, which he carried in a cloth bag. Whenever hunger struck, he would scoop some flour into a mug and mix it with hot water—his entire meal.

Colleagues often brought him proper meals, but he couldn’t bring himself to eat even a bite. When he didn’t have his flour bag with him, he would make up an excuse to skip the meal. He also had a well-worn sheepskin coat he had used for over a decade. In Daqing, he practically lived on the drilling site, sometimes not returning home for several days and nights. In the biting cold, that coat was his only protection against the wind. When tired, he would use drill pipes as bedding, drill bits as pillows, and the sheepskin coat as a blanket. On warmer days, he would lay the coat on the ground and nap for a few minutes after intense labor. That old coat had followed him from Yumen to Daqing and became an indispensable part of his life.

Wang always believed: “To work is to practice Marxism-Leninism; without action, there is no Marxism-Leninism at all.” In study, he was practical and persistent; in work, he took pride in hardship; in production, he demanded high standards; in life, he remained humble and austere.

He had a strict rule at home: “Not a penny of public property can be touched.” His heart was always with the workers and the people. As a team leader, he lived at the drilling site, constantly circling around the rig. Later, as brigade leader and deputy commander, he never stopped “running rigs,” overseeing dozens of them with tireless dedication. He was full of compassion for the people and steely in self-discipline—never greedy, never corrupt, content to live as a humble ox, laboring for the Party and the people all his life.

Despite hardships in his personal life, Wang never used his position for personal gain. His wife had worked for years as a temporary laborer—while others in the same position had been promoted to permanent status, she remained stoking boilers and feeding pigs at the site. Many of his relatives lived in Yumen—nephews, cousins, a whole group. Letters from home pleaded with him to transfer just one or two to Daqing due to the dire conditions in the northwest, but Wang never did it—not a single one.

Recognizing his family’s financial struggles, the authorities granted a 30-yuan monthly subsidy. Yet Wang never collected it himself—he let the labor union distribute it to workers in greater need. He suffered from severe arthritis, and the organization assigned him an old jeep to help with his work. Though aged and worn, the vehicle proved useful—for traveling to rigs, transporting supplies, delivering food, taking workers to hospitals, and bringing them home.

Wang had a rule about the jeep: if he saw workers by the roadside—whether he knew them or not—he’d offer them a ride. If there wasn’t enough space, he would get out himself and let the driver take the workers. The only ones forbidden from riding in the car were his own family. When his elderly mother, over 60, fell ill, it was Wang’s eldest son who took her to the hospital on a bicycle.

Although his family was large, they lived in the same basic “earth block” houses as everyone else. Their home contained nothing but beds—there wasn’t even enough space to walk. Yet even in these conditions, Wang helped others. For a time, his house became a “guesthouse” for visiting family members of colleagues who had nowhere else to stay. One elderly worker’s family lived with them for over half a year.

That was Wang Jinxi—he had no room in his heart for himself, only for the people. His love for them was selfless, sincere, and embodied the Communist Party’s fundamental mission: to serve the people wholeheartedly.