Looking back through history, the development of China’s college entrance examination system has been anything but smooth.

From the official establishment of a standardized university admission test in 1952 after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, to its forced interruption during the Cultural Revolution—when higher education was severely disrupted and talent cultivation faced a major rupture—it wasn’t until 1977, under Deng Xiaoping’s resolute decision, that the exam was reinstated, injecting fresh vitality into national development. This significant historical turning point not only transformed countless lives but profoundly influenced China’s societal trajectory.

After the founding of the new nation, a unified college entrance exam system was established in 1952, but was soon abolished with the onset of the Cultural Revolution. Higher institutions ceased recruitment, educated youth were sent to rural areas, university professors were relocated to “May Seventh Cadre Schools” for manual labor, and higher education was completely paralyzed.

In 1970, a handful of universities such as Peking University and Tsinghua University began enrolling worker-peasant-soldier students. By 1971, colleges and universities nationwide resumed admissions—but operated under the principle of “voluntary application, mass recommendation, leadership approval, and institutional review,” without entrance exams. Instead, they mostly admitted junior high school graduates who had undergone two or more years of labor as workers, peasants, or soldiers.

To improve college education quality, Premier Zhou Enlai proposed allowing secondary school graduates to directly enter universities. However, his suggestion was criticized as part of a “revisionist educational trend” and was suppressed by the “Gang of Four.”

In 1975, when Deng Xiaoping oversaw a nationwide rectification, he attempted some pilot programs to select outstanding students directly via exams after high school—but his efforts were again interrupted by his political purging. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, the nation was acutely concerned: Who would lead higher education? What would universities do? How would talent be cultivated?

Deng realized that compared to developed countries, “our science, technology, and education are lagging by 20 years,” and more urgently, the nation faced “a severe shortage of successors in education, from primary school through university.” Anxious to correct this gap, he resolved that “talk alone won’t achieve modernization—it requires knowledge and talent.” He promised: “We must invest great effort to make up for lost time.” Upon returning to power, Deng volunteered to take charge of education and science policy, and formulated comprehensive plans to rectify the educational system, including college entrance exams.

On July 23, 1977—just days after his reinstatement at the Third Plenum of the 10th CPC Central Committee—Deng declared in a meeting with Changsha Institute of Technology leaders: “No matter how many university students we enroll this year, there must be exams. If they fail, don’t accept them.”

On July 29, during briefings by Fang Yi and Liu Xiyao, he emphasized again: “We must adhere to examinations, especially in key schools. Those who fail must repeat. We must take a firm stance.” At that time, the national admissions scheme drafted earlier in summer still followed “voluntary sign-up, mass recommendation, leadership approval, institutional review.”

Although Deng was anxious, he acknowledged the education system was devastated by the Cultural Revolution. His approach was phased: “Allow one year for preparation, then next year implement a dual-path system: half through exams, half through other routes… this year we transition, next year full implementation.” Deng agreed to proceed under existing methods for 1977 while preparing the exam restoration.

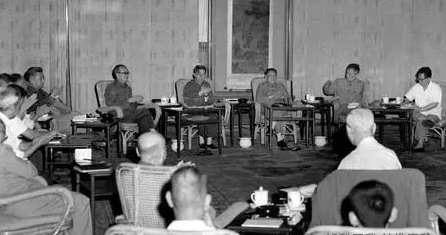

On August 4, the Ministry of Education submitted the transfer report titled “Opinions on the 1977 Admissions Work of Higher Education Institutions” to the State Council. That same day, Deng hosted and chaired the five-day Science and Education Work Symposium. He demanded, “We must research and finalize the exam system this year: testing, grading, teacher training, admissions, assessment—all to prepare for implementation next year in key universities and then expand.”

On August 6, during the symposium, Associate Professor Zha Quanxing of Wuhan University bluntly stated that the main issue was the admissions system, and that exams must be reinstated immediately. His remarks resonated with other experts like Wu Wenjun and Wang Daheng, who advocated postponing enrollment by two months to save quality.

Deng personally asked Minister Liu Xiyao: “Is it still feasible this year?” Liu replied, “Yes, we can delay admissions.” Deng immediately approved the change, instructing him to retrieve the earlier admissions report and rewrite it accordingly: “We need a method that selects excellence without causing turmoil.”

He approved dropping the phrase “unit approval” from the process, noting, “If a student applies but his unit disagrees, he would be stuck. That must go.” On August 8, he confirmed: “This year we firmly restore admission by direct exam of high school graduates, abandoning recommendation.”

Following the symposium, the Ministry drafted a revised report on delaying admissions and new student enrollment. It stated: “Admissions were originally planned for August with term start in mid-November; now we propose delaying to the fourth quarter, with freshmen entering by late February next year—a three-month delay including winter break.” On August 18, Deng endorsed it: “This ensures quality students in key universities.” Other top leaders including Hua Guofeng, Ye Jianying, and Li Xiannian reviewed and agreed.

Thus, the decision to restore exams was set.

Implementation was not easy. Without Deng’s continued leadership, even with top-level consensus, test restoration wouldn’t happen. On August 13, the Ministry convened a nationwide admissions conference. Disagreement over abolishing recommendation and restoring exams delayed the meeting until mid-autumn.

An inside joke emerged: “The admissions meeting convened twice, too many opinions, no agreement. Though the east wind is strong, the gate is still closed.” The root issue: the persistent “two whatevers” (policy constraints treating the Cultural Revolution as correct) still bound decision-making. Reforming the system involved liability risk. Deng sharply rebuked officials: “The Ministry must not obstruct. You either support central policy—then act—or don’t—then change jobs.”

Under his decisive leadership, the conference concluded in days, and draft opinions were finalized. Then Deng personally pushed for swift approvals: On October 3 he submitted key draft reports to Hua Guofeng and others saying, “This is urgent—please have Politburo discuss soon.” On October 5, the Politburo approved the plan. Over the following days, Deng, Hua, Ye, Li and others reviewed and approved the document, which was formally issued by the State Council on October 12.

The policy established reforms to restore unified testing and merit-based admission. In winter 1977, after a decade’s suspension, the national college entrance exam finally took place. 5.7 million passionate youth rushed into exam halls; 273,000 were admitted. The group included workers, peasants, soldiers, sent-down youth, recent high-school graduates, and public-sector staff.

In summer 1978, 6.1 million candidates took exams; 402,000 were admitted. The timely restoration of exams overcame the severe talent shortfall after the Cultural Revolution, supplying essential manpower for reform, modernization, and modernization efforts. This pivotal reform also marked the ideological shift toward “liberating the mind and seeking truth from facts” at the Third Plenum—a fundamental cornerstone for China’s reform and opening-up.

Over 40 years later, the annual college entrance exam remains a key focal point of national attention. It carries the dreams of students and families, embodying the hopes of the nation. The exam’s resumption has become a powerful historical symbol, and Deng Xiaoping’s strategic vision, political courage, and decisive leadership remain etched in our collective memory.