“There are only three treasures in Bao’an: flies, mosquitoes, and oysters from Shajing. Nine out of ten houses are empty—only the old and the young remain.”

This was a popular folk rhyme circulating in Bao’an County, Guangdong Province before China’s Reform and Opening-Up.

Behind this rhyme lies a staggering set of numbers: since the emergence of the “Escape to Hong Kong” phenomenon in 1955, Bao’an witnessed four major waves of mass migration, occurring in 1957, 1962, 1972, and 1979. In total, there were approximately 560,000 border-crossing attempts. These participants came not only from Guangdong, but also from provinces like Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi, and others—spanning 62 cities across 12 provinces in China.In 1977, China stood on the eve of a sweeping transformation.On February 26, 1978, the Government Work Report delivered at the First Session of the Fifth National People’s Congress declared: “The entire national economy was on the verge of collapse.” According to official statistics, at least 200 million rural residents still struggled to meet basic subsistence needs, and many lived in extreme poverty. While urban residents had access to state-provided welfare, wages for workers had remained stagnant for two decades. Essential consumer goods were rationed with coupons, housing shortages were severe, and tens of millions of educated youth, demoted cadres, intellectuals, and other displaced urban residents were eager to return to the cities. Over 20 million people in urban areas were waiting for jobs.

In November 1977, shortly after his political comeback, Deng Xiaoping chose Guangdong as his first stop on a national inspection tour. At the time, the massive cross-border exodus to Hong Kong was viewed as a politically destabilizing crisis. Provincial officials, when briefing Deng on the situation, could not avoid discussing the escalating wave of escapees. Upon hearing the severity of the “Escape to Hong Kong” issue, Deng remarked: “This is not something the military can manage. This is a policy issue.”

When poverty reaches its peak, change becomes inevitable.

How could Guangdong curb the ongoing migration crisis? On April 5, 1978, Xi Zhongxun was appointed to head south and take charge. The very next afternoon, on April 6, at the First Plenary Session of the 4th Guangdong Provincial Party Committee, Xi Zhongxun was elected Second Secretary. Shortly thereafter, First Secretary Wei Guoqing returned to Beijing, and the responsibilities for governing Guangdong fell to Xi

Ju Liming, former Deputy Secretary-General of the Guangdong Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China, once recalled that when Xi Zhongxun first arrived in Guangdong, he stayed in Building No. 4 of the Zhudao Hotel. Just outside the transportation office, there was a small stall selling fish and meat. At that time, both items required ration coupons and long queues. Some elderly residents would line up as early as three or four in the morning, placing small bricks or stools to reserve their spots.

Xi Zhongxun himself would sometimes join the queue around 5 a.m., standing alongside the common people to personally experience their daily hardships. Later, at a provincial committee meeting, he remarked:

“Guangdong is blessed with a spring-like climate year-round—it is known as a land of fish and rice. But in this so-called ‘land of fish and rice,’ people can’t even buy fish. Fish like ribbonfish, which used to be tossed away as fertilizer, are now considered a luxury. This is unacceptable. We must free our minds. Building socialism does not mean staying poor—we must improve people’s living standards as quickly as possible.”At that time, the number of people fleeing Guangdong to Hong Kong illegally peaked at 20,000 to 30,000 per month. In early July 1978, on his first field inspection after taking office, Xi Zhongxun chose to visit Bao’an County, the area most affected by the “Escape to Hong Kong” crisis.

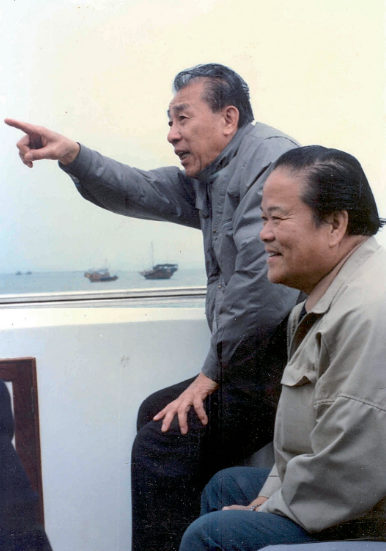

At Shatoujiao’s Sino-British Street, he observed the stark contrast: on the Hong Kong side, the streets bustled with traffic and prosperity; on the Bao’an side, the atmosphere was bleak and desolate. Although separated by only a narrow river, the standard of living between the two places was worlds apart.

In 1978, the average annual income of villagers in Luofang Village, Shenzhen, was just 134 yuan, while across the river in Hong Kong, villagers earned more than 13,000 Hong Kong dollars per year—and at that time, the Hong Kong dollar was significantly stronger than the yuan. The gap was staggering.Through firsthand investigation, Xi Zhongxun formed a clear understanding of the root cause: the fundamental solution to mass border escapes was to develop the economy and improve people’s livelihoods. After hearing the Bao’an County officials’ report on attracting foreign investment, promoting light industry, and encouraging small-scale trade, he immediately responded:

“If you want to do it, then just do it—don’t wait.”

As long as production could be increased and the people’s lives could be improved, they had his full support.Under Xi Zhongxun’s leadership, Guangdong became the first province in China to loosen economic controls, significantly reducing the number of goods under mandatory state purchase and resale policies—from over 100 items down to just over 20, and eventually to only 8. As a result, the availability of goods surged, and people’s living standards improved dramatically.

One of the most profound influences on China’s understanding of the outside world—and a powerful driving force behind the Reform and Opening-Up policy—was the wave of overseas fact-finding delegations. In 1978 alone, at least four major delegations were dispatched directly by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC):

From March 10 to 31, the CPC Delegation of Party Cadres, led by Li Yimang with Yu Guangyuan and Qiao Shi as deputy heads, visited Yugoslavia and Romania.rom March 28 to April 22, an economic delegation from Shanghai, led by Lin Hujia, Secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Committee, traveled to Japan.From April 10 to May 6, the Hong Kong and Macau Economic and Trade Delegation, headed by Duan Yun, Vice Chairman of the State Planning Commission, conducted a visit.From May 2 to June 6, Vice Premier Gu Mu led a high-level delegation on a mission to five Western European countries: France, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, and West Germany.Meanwhile, Deng Xiaoping himself carried out a series of pivotal foreign visits to promote diplomatic ties and gather insights into global development models. In October 1978, he visited Japan, marking a historic step in Sino-Japanese relations. From November 5 to 14, he toured Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore, further strengthening China’s engagement with its Asian neighbors.

These visits not only opened a window for China to observe international advancements in science, technology, and governance, but also played a critical role in shaping the vision and direction of China’s economic reforms.

In early April 1978, the State Planning Commission and the Ministry of Foreign Trade organized an economic and trade delegation to Hong Kong and Macau, led by Vice Chairman Duan Yun of the State Planning Commission. During their visit, the delegation witnessed firsthand the rapid economic development of Hong Kong and Macau. What struck them most was that Hong Kong, despite having no arable land or natural resources, had managed to achieve remarkable growth by importing advanced foreign technologies, equipment, and capital. This experience had a profound impact on the members of the delegation, challenging their previous assumptions and broadening their perspectives.On May 6, after the inspection tour, the delegation held a joint meeting in Guangdong with provincial leaders Xi Zhongxun and Liu Tianfu. They collectively proposed to the central government that Bao’an County and Zhuhai County, due to their proximity to Hong Kong and Macau, be designated as export-oriented industrial bases—a suggestion that was soon approved by central authorities.

On May 31, 1978, the delegation submitted the “Hong Kong and Macau Economic Inspection Report (Outline for Briefing)” to the central government. The report pointed out that Bao’an and Zhuhai, adjacent to Hong Kong and Macau, had unique geographic advantages for developing export-oriented industries—advantages that few other regions could match. Earlier that March, teams from the State Planning Commission, Ministry of Foreign Trade, and Guangdong Province had already visited the two counties and, in coordination with the Hong Kong and Macau Work Committee, drafted a plan. The plan envisioned transforming Bao’an and Zhuhai over three to five years into:Integrated industrial and agricultural production basesExport processing hubsTourist destinations to attract visitors from Hong Kong and MacauModernized border cities with economic and strategic importanceThe report made several bold and innovative recommendations, including:Granting special administrative measures for Bao’an and ZhuhaiUpgrading them to provincial-level cities (equivalent to prefecture-level) with stronger leadership teamsStreamlining import and export processes: allowing local products and required materials to be handled directly by trade offices in Hong Kong and Macau, without the need for repetitive central approvalsEstablishing duty-free shops to serve incoming travelers, with supply chains managed as though for exportVigorously expanding export-oriented processing businesses by leveraging resources from Hong Kong and Macau

This report marked the first official proposal to establish special economic zones (SEZs) in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. It was groundbreaking in its call for special policies to accelerate China’s opening to the outside world, urging that this be treated as a priority national development strategy.In retrospect, this initiative was China’s first substantive step toward the creation of Special Economic Zones—a policy that would later transform China’s economic landscape and open a new chapter in its modernization journey.

Similarly, in Guangdong Province, which was geographically close to Hong Kong and Macau and thus more attuned to external influences, the provincial leadership made efforts to broaden the horizons of local officials. The Guangdong Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China organized an inspection delegation composed of Party secretaries from all prefectures, led by Yang Yingbin, a member of the Standing Committee and Secretary-General of the provincial committee, to visit Hong Kong and Macau.

Ju Liming, former Deputy Secretary-General of the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee, recalled this initiative vividly:

“Xi Zhongxun personally contacted the Party secretaries of all eight prefectures across the province, including Lin Ruo, Party Secretary of Zhanjiang, and Ma Yipin, Party Secretary of Shaoguan. At that time, it was unheard of for farmers to go abroad on official study tours. However, the Party Branch Secretary of Yongda Production Brigade in Xiaolan Town, Zhongshan County, led a team of farmers to conduct an overseas inspection. After the Guangdong provincial government approved their application, it was escalated to the State Council and officially sanctioned. This marked the first-ever case in China of farmers being allowed to travel abroad for research purposes.”This inspection trip played a significant role in Guangdong’s ideological liberation and reform movement. As Ju Liming put it:

“It was precisely because Xi Zhongxun embraced open thinking that the flame of ideological emancipation in Guangdong was ignited so quickly.”Near an intersection close to Shekou Port in Shenzhen, a brown-red signboard stands on a patch of green. Written in large golden Chinese characters are the words:

“Time is money, efficiency is life.”This slogan, which has since resonated throughout China, was created by Yuan Geng, a visionary leader hailed as:

the former Executive Vice Chairman of China Merchants Group, the founder of the Shekou Industrial Zone, China Merchants Bank, and Ping An Insurance, as well as a key architect of the second rise of the century-old China Merchants Group, and a major pioneer in China’s Reform and Opening-Up movement.

The central government’s decision to develop an “export base” near Hong Kong came at a crucial time—and offered a turning point for the struggling China Merchants Group in Hong Kong. At the time, Yuan Geng, Executive Vice Chairman of the China Merchants Group Board in Hong Kong under the Ministry of Transport, spent two months conducting in-depth research. Based on his findings, he drafted a proposal titled:“A Request to the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Fully Utilizing the China Merchants Group in Hong Kong.”

In the report, Yuan proposed a bold strategy of “breaking constraints and going all out.” The proposal was submitted on October 9, 1978, and just three days later, on October 12, all five top leaders of the central government endorsed it. They gave clear instructions to adopt the following guiding principle:“Root in Hong Kong and Macau, rely on the mainland, face overseas markets, operate with diverse methods, combine industry and commerce, integrate buying and selling.”

However, due to the high land prices in Hong Kong, implementation proved difficult. Yuan Geng then turned his attention across the border—to Bao’an County. His idea quickly received full support from the Guangdong Provincial Committee.On January 6, 1979, the Guangdong Provincial Government and the Ministry of Transport jointly submitted a report to the State Council titled:“Regarding the China Merchants Group in Hong Kong Establishing an Industrial Zone in Bao’an County, Guangdong.”

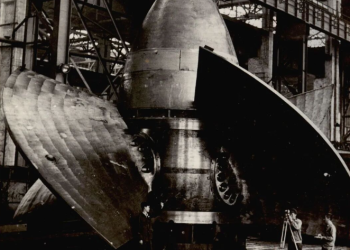

The report stated:“The China Merchants Group in Hong Kong requests to establish a series of industrial enterprises related to transportation and shipping in the coastal areas of Bao’an County, Guangdong, adjacent to Hong Kong. After joint research, we unanimously agree to allow the China Merchants Group to establish an industrial zone in this region. This will not only take advantage of the mainland’s cheaper land and labor, but also leverage foreign capital, advanced technology, and raw materials, fully integrating the strengths of both sides. It will greatly promote the modernization of our transportation industry, boost industrial development in the border city of Bao’an, and contribute to the overall construction efforts in Guangdong Province.”

This report drew serious attention from Li Xiannian, then Vice Chairman of the CPC Central Committee. Not long afterward, he summoned Yuan Geng for a meeting. Yuan brought a map, and Li used a pencil to draw a circle over the Nantou Peninsula, generously offering him the entire peninsula. Yet Yuan Geng, constrained by limited vision at the time, only requested 2.14 square kilometers in Shekou. Years later, he deeply regretted this decision, admitting that he had not been “liberated enough in thought.”

Thus, the China Merchants Shekou Industrial Zone in Hong Kong was officially established in early 1979, even before the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was founded.According to Chen Yusheng, former publicity director of Shenzhen’s Nanshan District, the iconic slogan“Time is money, efficiency is life”originated from Yuan Geng’s early experiencesworking in Hong Kong.

At the time, Yuan was negotiating a deal with a Hong Kong businessman to purchase a building worth tens of millions of Hong Kong dollars. They signed the contract at 2 p.m. on a Friday and planned to dine together afterward. However, the Hong Kong businessman declined the dinner invitation, explaining that he needed to immediately deposit the funds into the bank. Since banks were closed on weekends, even an hour’s delay in deposit would lose thousands of dollars in interest at the then floating rate of 14%.

This moment left a lasting impression on Yuan Geng, who considered it his first real lesson from Hong Kong.In March 1981, during a staff meeting at the industrial zone, Yuan Geng publicly introduced the now-famous slogan for the first time. At the time, it was part of a six-part motto:“Time is money, efficiency is life. The customer isGod. Safety is law. Everyone has something tomanage, and everything has someone responsible.”

Later, Xu Zhiming, Deputy Party Secretary of the Shekou Industrial Zone, was entrusted by Yuan Geng to oversee the implementation of the slogan. He commissioned the creation of a signboard painted in red, emblazoned with the words:“Time is money, efficiency is life.”This iconic sign was erected in front of several buildings belonging to the zone’s command center.Around the same time, another powerful slogan emerged:“Heroes are judged not by their origins, but by their talent and character.”In Shekou, issues like household registration (hukou) and personnel files were no longer barriers. The question most frequently asked during job interviews in Shekou became:“What can you do?”Thanks to this open and pragmatic attitude, talent from all walks of life flooded into Shekou—and into Shenzhen. These early pioneers, builders of the special economic zone, brought unprecedented vitality to this once-sleepy coastal town.

The reform of the Shekou Industrial Zone was grounded in one core principle: improving work efficiency, economic performance, and social benefits. It embraced market-oriented reforms, moved boldly, and implemented supporting policies simultaneously. Despite skepticism and resistance, Shekou proved itself: with only 2% of Shenzhen’s population, it generated 16% of the city’s total profit.

From abolishing the “iron rice bowl” system to attracting foreign investment, from the commercialization of housing to national-level talent recruitment, Shekou achieved 24 national firsts between 1979 and 1984.The remarkable success of Shekou’s experiment was soon hailed by the media as the “Shekou Model,” positioning it as the vanguard of China’s economic zones.Meanwhile, as Shekou’s transformation was taking shape, a major turning point unfolded in Beijing. In December 1978, the Third Plenary Session of the 11th CPC Central Committee marked the official beginning of China’s era of Reform and Opening-Up.

Shortly after, in January 1979, the Guangdong Provincial Committee convened an enlarged Standing Committee meeting and reached a consensus: to leverage Guangdong’s proximity to Hong Kong and Macau, attract foreign capital, introduce advanced technology and equipment, develop compensation trade, and pursue assembly processing and cooperative operations.On January 16, 1979, Wu Nansheng and Ding Lisong were dispatched to Shantou to promote the spirit of the Third Plenary Session. Shantou was Wu Nansheng’s hometown.

Historically, Shantou was considered the gateway to eastern Guangdong and a strategic hub of southern China. Over a century ago, Friedrich Engels once described it as “the only city in the Far East with a commercial essence.” In the 1930s, it was even nicknamed “Little Shanghai.”

But Wu was deeply shocked by what he saw upon returning home. The buildings he once knew were now dilapidated and crumbling. The streets were lined with makeshift bamboo shacks, crudely assembled and chaotic—a stark contrast to the city’s former glory.

On March 3, at a meeting of the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee Standing Committee, Wu Nansheng stated:“I propose that Guangdong take the lead. Let’s designate a specific area in Shantou as a pilot zone, using preferential policies to attract foreign investment and bring in advanced technologies and practices from abroad.

On March 3, at a meeting of the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee Standing Committee, Wu Nansheng stated:“I propose that Guangdong take the lead. Let’s designate a specific area in Shantou as a pilot zone, using preferential policies to attract foreign investment and bring in advanced technologies and practices from abroad.

There are three reasons:

First, aside from Guangzhou, Shantou handles the most foreign trade in the province, generating around $100 million in foreign exchange annually. It has substantial experience in international economic activity.

Second, the Chaozhou-Shantou region is home to the largest number of overseas Chinese worldwide, accounting for about one-third of all overseas Chinese from China. Many of them are influential figures abroad, and we can mobilize them to invest back home.

Third, Shantou is located in eastern Guangdong, somewhat remote; even if the pilot fails, the overall impact would be minimal.”

At the time, the Guangdong Provincial Committee had also received a proposal from Bao’an County suggesting the development of Shenzhen into an export base. During the internal discussions, the committee unanimously supported the concept, and even expanded upon it.“Guangdong should not only establish an export processing zone in Shantou, but also in Shenzhen and Zhuhai,” they agreed.

Xi Zhongxun, present at the meeting, voiced his full support:“If we’re doing this, then let’s do it across the entire province! Draft a proposal—I’ll take it to Beijing during the April Central Working Conference.”

On April 1st and 2nd, under the chairmanship of Yang Shangkun, the Guangdong Provincial Standing Committee formally approved the idea of requesting central authorization to “let Guangdong take the lead.” With a clear consensus on setting up export industrial zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shantou, the next hurdle became: what should we call them? Naming the initiative sparked considerable debate.

Before heading to Beijing for the Central Working Conference, Xi Zhongxun and Wu Nansheng first reported Guangdong’s plan to Marshal Ye Jianying, who was then in Guangzhou. Marshal Ye was delighted and urged them:“You must report this to Comrade Xiaoping as soon as possible.”

On April 17, 1979, the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee convened a briefing session for the conveners of various groups attending the Central Working Conference. Xi Zhongxun presented Guangdong’s situation in detail, and solemnly proposed:“Given Guangdong’s geographical proximity to Hong Kong and Macau, it should fully leverage this advantage to pioneer opening-up policies.”

He suggested setting up special zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and the overseas Chinese hub of Shantou, modeled after foreign export processing zones. These areas would be separately managed, designated as investment hubs for overseas Chinese, Hong Kong and Macau compatriots, and foreign businesses. Production would be organized based on international market demand.At the time, the proposed name for these areas was:“Trade Cooperation Zones.”

While listening to Xi Zhongxun’s report, Deng Xiaoping interjected with a telling remark:“Singapore attracts foreign investment to set up factories and can retain 50% of the profits. It also generates income through labor and taxation. Guangdong and Fujian have similar conditions. We can build special provinces by leveraging overseas Chinese capital and technology, including setting up factories. As long as we don’t violate major principles, we can make substantial progress within a few years.”

He expressed strong support for Guangdong’s bold proposal to decentralize certain powers and experiment with “Trade Cooperation Zones,” which he considered innovative and pragmatic.

In fact, back in June 1978, Deng had already mentioned, during a briefing by Gu Mu, the concept of foreign countries attracting investment through “Processing Zones,” “Free Trade Zones,” and “Free Ports.” At the time, over 80 countries and regions around the world had already established more than 500 export processing zones and free trade areas, showcasing their effectiveness in stimulating economic development.

When Deng Xiaoping heard that there was still disagreement over the name “Trade Cooperation Zone”, and a final decision had not been reached, he immediately responded:“Let’s just call them Special Zones. That’s what we called them back in the days of Shaan-Gan-Ning!”Here, Deng was referencing the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border Region—an early Communist revolutionary base area that also bore the term “special zone.” His choice of words was both historically grounded and forward-looking, signaling that economic reform could and should be

On April 28, 1979, following the conclusion of the Central Work Conference, Xi Zhongxun rushed back to Guangdong and immediately conveyed the conference spirit to the Provincial Party Standing Committee. During the transmission, he emphasized that Guangdong must take the lead—not just for Guangdong’s sake, but for the entire country. This was a national issue that required a strategic, forward-looking approach. Xi stated firmly:“If Guangdong doesn’t propose it today, it’ll be proposed tomorrow. If not tomorrow, then the day after. China’s development has come to a point where change is inevitable. If we don’t raise it, the Central Government will. Even if it costs us everything, we must do it.”

Following this, from May to June 1979, the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee held an expanded Standing Committee meeting and a three-tier cadre conference, to convey the central decision to allow Guangdong to take the lead and to mobilize the entire province to act on it. During this period, Marshal Ye Jianying, then in Guangzhou, met with provincial, municipal, and county-level officials. He offered earnest encouragement:“Work hard. Let Guangdong take the lead in reforming the economic management system.”

On July 15, 1979, the Central Committee issued a historically significant document:“Directive No. [1979]50” – The Approval by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council of the Reports from the Guangdong and Fujian Provincial Committees on Implementing Special Policies and Flexible Measures for Foreign Economic Activities.”

The directive stated:“The Central Government has decided to grant Guangdong and Fujian provinces special policies and greater autonomy in their foreign economic activities, enabling them to fully leverage their geographic advantages and seize the current favorable international climate. The goal is to take the lead in economic development. This decision is of strategic importance for accelerating China’s modernization.”

It continued:“The proposed economic management approach—a large-scale contracting system under unified central leadership—has been approved in principle for trial implementation.”“Regarding Export Special Zones, the trial will first be conducted in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. Once experience is gained, the potential for establishing similar zones in Shantou and Xiamen will be considered.”

On December 17, 1979, the first official meeting on establishing Special Zones was held in Beijing’s western suburbs. Known as the “Jingxi Meeting,” it was chaired by Gu Mu, with Wu Nansheng delivering the key report. Attendees included senior Guangdong officials Wang Quanguo, Fan Xixian, Qin Wenjun, Fujian’s Guo Chao, and officials from various central departments.Wu Nansheng’s briefing, titled:“Outline Report on Several Issues Regarding the Establishment of Economic Special Zones in Guangdong,”

marked the first formal proposal of the term “Economic Special Zone.”

Then, on March 24, 1980, the Central Government held another meeting with representatives from Guangdong and Fujian. It was during this meeting that the originally proposed term “Export Special Zone” was officially renamed:“Economic Special Zone”

After the approval of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), Wu Nansheng’s first priority was to draft and formulate the “Guangdong Provincial Regulations on Special Economic Zones.” Though the regulation contained just over 2,000 characters, it took more than a year to complete, undergoing 13 rounds of revisions from initial drafting to final release.

During the drafting process, the team referred to foreign legal frameworks but avoided direct copying. For example, the internationally common term “land rent” was originally considered. However, due to its association with the concept of “concessions” from pre-liberation China, it was carefully replaced with the more neutral phrase “land use fee.”

On August 26, 1980, Chairman Ye Jianying presided over the 15th Session of the Fifth National People’s Congress. At the meeting, Jiang Zemin, then Deputy Director of the State Import and Export Commission, presented an official explanation on behalf of the State Council regarding the establishment of SEZs and the enactment of the Special Economic Zone Regulations. The proposal was subsequently approved.

Later, on November 26, 1981, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress officially authorized Guangdong and Fujian provinces to formulate specific economic legislation for their respective Special Economic Zones.