At 9:32 a.m. on July 16, 1969, the Apollo 11 spacecraft lifted off. By 10:56 p.m. on July 21, it had achieved the first manned moon landing in human history, marking what is still considered one of the greatest milestones in space exploration.However, with the steady cancellation of the originally scheduled 2018–2024 U.S. lunar return timeline, it now seems that China’s 2030 lunar landing mission may be a more realistic path toward returning humanity to the Moon. In less than one traditional Chinese cycle (60 years), China’s aerospace achievements have been nothing short of astonishing. Looking back at the nation’s modest beginnings, we can find valuable lessons behind its current progress.

In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world’s first artificial Earth satellite.

By May 1958, Chairman Mao solemnly declared during the Second Session of the Eighth National Congress of the Communist Party of China:”We too will develop our own artificial satellite.”

This marked the beginning of China’s satellite development journey. Shortly thereafter, the Fifth Academy of the Ministry of National Defense and the Chinese Academy of Sciences began collaboration on satellite research. The “581 Group” was soon established under the Academy, with Qian Xuesen as the group leader and Zhao Jiuzhang and Wei Yiqing as deputy leaders.

In October 1965, entrusted by the Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, the Chinese Academy of Sciences held a landmark conference at Beijing Friendship Hotel to evaluate the overall plan for China’s first artificial Earth satellite. This meeting, known as the “651 Conference,” gathered over 120 experts and lasted 42 days.The participants held extensive discussions on the objectives and tasks of the satellite’s development and launch, ultimately producing four major documents:the overall system plan,the satellite platform design,the launch vehicle proposal, andthe ground support system plan.

In addition, the conference led to the compilation of 27 specialized research papers, totaling around 150,000 Chinese characters. The “651 Conference” remains a pivotal event in the history of China’s modern science and technology development.Space exploration has always been a long march. While countries like the Soviet Union and Japan once sprinted ahead—regardless of cost or by borrowing external resources—they ultimately failed to maintain their lead. This proves that a realistic and pragmatic scientific spirit is crucial for ensuring long-term, steady progress in China’s space program.

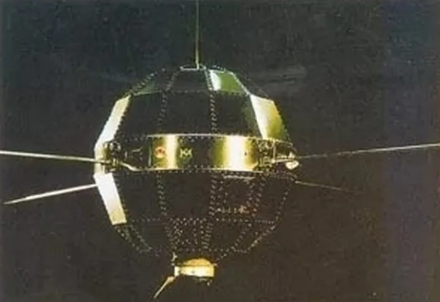

At the time, the design requirements for the Dongfanghong-1 satellite were clear and straightforward: once launched, it must be “trackable,” “audible,” and “visible.”The most challenging aspect was making it “trackable.” China adopted a Doppler tracking system, setting up multiple ground-based telemetry and control stations to receive signals transmitted by the satellite.

To ensure it was “audible,” engineers developed a solution that allowed a single transmitter to alternately broadcast both the “Dongfanghong” musical melody and telemetry data. The satellite carried a pre-recorded electronic version of the melody, played using aluminum plate chimes. The sound system was encased in epoxy resin to protect it from vibrations caused during launch and the satellite’s rotation in orbit.

To make the satellite “visible,” a great deal of effort was invested. Although the satellite body had already been designed with special materials and shapes to enhance reflectivity, the brightness from its own reflection was equivalent to that of a 7th-magnitude star, which is generally invisible to the naked eye, as humans can typically only see up to 6th-magnitude stars under perfect weather and lighting conditions.

To solve this, the research team developed a “visibility skirt”—a metallic film-coated structure installed on the third-stage rocket casing. After the satellite entered orbit and separated from the rocket, the skirt unfolded to a diameter of 4 meters. Under sunlight, the reflective skirt reached a brightness comparable to a 2nd-magnitude star, making it as bright as Polaris. On a clear night sky, this shining dot could indeed be seen from Earth.

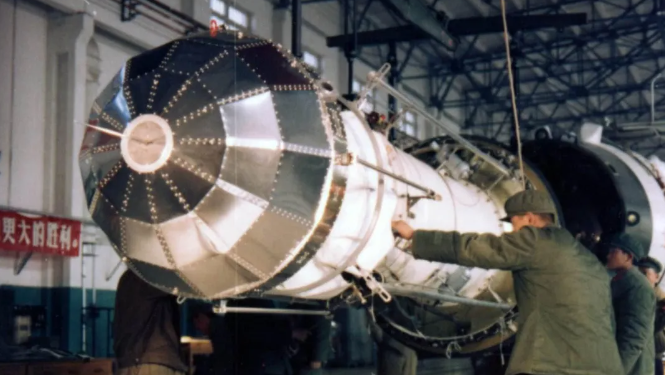

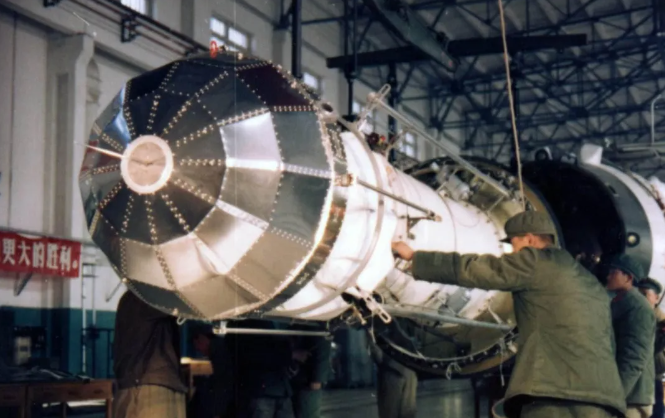

To ensure the satellite’s quality, it underwent meticulous assembly and was subjected to multiple comprehensive ground-based tests after final integration.

To ensure the satellite’s quality, it underwent meticulous assembly and was subjected to multiple comprehensive ground-based tests after final integration.

At 21:35 on April 24, 1970, China successfully launched the Dongfanghong-1 satellite from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province. With this historic achievement, China became the fifth country in the world—after the Soviet Union, the United States, France, and Japan—to independently develop and launch an artificial Earth satellite. This milestone significantly enhanced China’s international standing and ushered in a new era in the nation’s space exploration history. It marked a monumental leap from “having no satellite” to “having one of our own,” laying the foundation for the development of China’s space industry.

The Dongfanghong-1 satellite weighed 173 kilograms, surpassing the combined weight of the first artificial satellites launched by the Soviet Union, the United States, France, and Japan. It operated in an elliptical orbit with a perigee of 439 kilometers, an apogee of 2,384 kilometers, and an inclination of 68.5 degrees, with an orbital period of 114 minutes. Thanks to its high orbital inclination and robust launch capabilities, the satellite remains in orbit to this day.

To commemorate this historic achievement and carry forward the spirit of aerospace innovation, in 2016, with approval from the Central Government and the State Council, April 24 was officially designated as “China Space Day”, to be observed annually starting that year.

The Dongfanghong-1 satellite was designed as a near-spherical 72-faced polyhedron, with a diameter of approximately 1 meter and a mass of 173 kilograms. Its surface was made of thermally controlled aluminum alloy, specially treated for temperature regulation in space. The satellite was also equipped with four 2-meter-long whip antennas to support communication functions.

The primary mission of the Dongfanghong-1 satellite was to test key technologies such as the satellite platform, orbital control, and thermal regulation. It broadcasted the song “The East Is Red” at a frequency of 20.009 MHz, while also serving to monitor the ionosphere and measure atmospheric density.

Powered by silver-zinc storage batteries, the satellite was designed for a 20-day mission lifespan, but it operated for 28 days, far exceeding expectations.

During development, engineers overcame numerous technical challenges, including satellite attitude control (achieving spin stabilization at 120 rotations per minute), thermal vacuum simulation, and the creation of an infrared horizon sensor. The mission also pioneered the development of a Doppler velocity-based orbit determination system—a first in China’s space technology history.

The thermal control coating and spin stabilization technology used in Dongfanghong-1 provided valuable references for the development of subsequent recoverable satellites and meteorological satellites.

As of 2025, Dongfanghong-1 has remained in orbit for 55 years, and its high reliability and long-lifespan design philosophy continue to serve as an inspiration for modern satellite engineering