He was a man who only studied up to the fourth grade in primary school, once an apprentice in a fabric store and later a small lock factory owner. Amid the flames of the War of Resistance Against Japan, he led seven workers and ten machines from the Shanghai-based Liyong Hardware Factory on a journey spanning thousands of miles to reach Yan’an. In Yan’an, he made outstanding contributions to the border region and the anti-Japanese war effort, earning the praise of Mao Zedong and Lin Boqu, who called him the “Father of Border Region Industry.”

In 1958, as a delegate to the Eighth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, he wrote to Chairman Mao, volunteering a bold proposal—to build China’s first 10,000-ton hydraulic press in Shanghai using a method he called “ants gnawing at bones.”

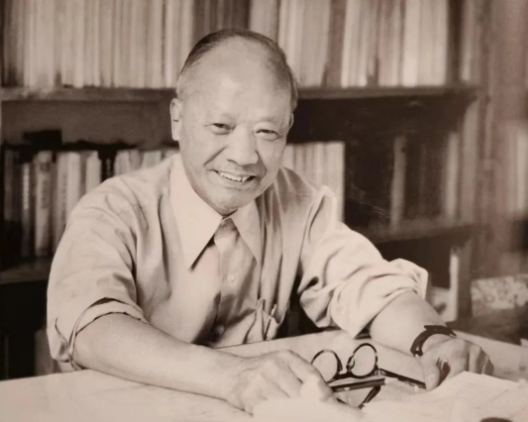

One after another, his breakthroughs in independent innovation and scientific research led this man—Shen Hong—to become a nationally renowned master craftsman. Ultimately, he was selected as one of the first academicians of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

On May 19, 1906, Shen Hong was born into a small workshop-owning family in Xianshi Town, Haining County, Zhejiang Province. At the age of seven, his father died of illness, leaving him and his mother to struggle in poverty. In 1917, just as he was finishing the fourth grade of primary school, Shen had to drop out due to illness but persisted in teaching himself.

In 1919, he went alone to Shanghai’s Hongkou District and became an apprentice at the Xietai New Fabric Shop under Wu Yuecheng, beginning a life of self-reliance.

Diligent and curious by nature, Shen got up every day at five or six in the morning to do chores and learn the skills of selling fabric. Near the fabric shop were several small machine factories. Whenever he had spare time, Shen would visit these factories to watch the workers at their machines, often becoming entranced by a particular device.

On one occasion, he spent more than one yuan to buy a pocket watch, determined to figure out how its hour and minute hands moved in such perfect coordination. For days, he disassembled and reassembled the watch repeatedly. Later, Shen would often say that his journey as an engineer began with repairing clocks and watches.

After the May Fourth Movement, the Sixth Commercial Federation in Hongkou opened a night school, and Shen eagerly enrolled. In the autumn of 1924, he saw that the Commercial Press was selling a book titled The World’s Ten Most Successful People, and he bought a copy, reading it over and over. The stories of scientists and inventors like Edison, Faraday, and Watt—who studied hard and dared to innovate—deeply inspired and motivated him.

Through years of self-study and hands-on practice, Shen developed a keen interest in pin tumbler locks. He purchased one, quickly took it apart, and studied its structure. But disassembly was easy—reassembly was the challenge. After several failed attempts to put the lock back together, he went to a locksmith for guidance. After watching the master reassemble it, Shen returned to the fabric shop, took it apart again, and reassembled it by himself. Repeating this process many times, he finally mastered the lock’s internal structure and assembly techniques.

In 1931, Shen Hong politely declined repeated requests from his mentor Wu Yuecheng to stay and left the Xietai New Fabric Shop after working there for 12 years. Together with colleagues Zhang Nianchun, Cai Landa, and others, he pooled 5,000 yuan in capital and spent 3,500 yuan to purchase a full set of equipment for lock manufacturing. He also personally designed and built several small, specialized tools. In December 1931, the “Liyong Hardware Factory” officially opened in Hongkou, marking Shen Hong’s transformation into a small entrepreneur in Shanghai dedicated to the vision of saving the nation through industry.

To craft his very first pin tumbler lock, Shen scoured the local markets for various types of locks, disassembled them one by one, and repeatedly compared and analyzed their mechanisms to identify their strengths and weaknesses. He then created his own design, optimized the structure, and conducted trial after trial. At last, he successfully produced his first high-quality pin tumbler lock, which soon went into mass production.

Shen branded his factory’s locks under the trademark “Dog” , symbolizing a guard dog protecting the door.

The “Dog” brand locks were comparable in quality to imported Western locks but sold at significantly lower prices. They quickly gained a foothold in the Shanghai market and were even exported to Hong Kong, Macau, and several Southeast Asian countries. Naturally, this sparked both surprise and resentment among foreign competitors. The American Yale Company first attempted to buy out Liyong Hardware Factory with a generous offer, but Shen firmly refused. The company then launched a price-cutting campaign in an effort to drive Liyong out of business.

But Shen refused to back down. He firmly believed that with diligence and technical mastery, Chinese people were fully capable of manufacturing the same high-end products that foreigners monopolized. And as long as the quality was good, Chinese consumers would choose domestic brands.

The success of the “Dog” brand pin tumbler lock opened up the market, allowing the Liyong Factory to accumulate both capital and technical expertise. Shen Hong gradually expanded production, moved into manufacturing small machine tools, and even began venturing into the field of automobile manufacturing. Just as he was full of ambition and ready to make a greater impact, the full-scale outbreak of the War of Resistance Against Japan in 1937 brought devastation to Shanghai as Japanese imperialist forces ignited the flames of war in the city.

At a time of national crisis, the National Resources Commission of the Kuomintang government convened to discuss how to preserve Shanghai’s many factories and industrial equipment—this vital industrial hub had to be protected. They ultimately decided to relocate factories to safer areas.

On the evening of August 25, 1937, Shen Hong rented two civilian boats and, together with his factory workers, set sail from the Suzhou River with ten heavy machines weighing more than ten tons. They were among the first batch of factories to relocate. After enduring countless hardships, they arrived in Wuhan in late September and temporarily established the “Liyong Wuchang Factory.”

On December 13, as Nanjing fell to the invading Japanese forces and Wuhan faced imminent danger, the government ordered further relocation inland. By chance, Shen Hong attended a lecture by journalist Fan Changjiang from Ta Kung Pao, where he learned about the situation in Yan’an. The idea of heading to Yan’an began to take shape in his mind.

Shortly thereafter, he ran into an old night school classmate from Shanghai, Chen Zhenxia, who shared news of the Eighth Route Army’s great victory at the Battle of Pingxingguan. This deeply inspired Shen and reinforced his belief that the Communist Party was the true hope for winning the war against Japan, further strengthening his determination to go to Yan’an.

Shen Hong then wrote a letter to the Eighth Route Army’s office in Wuhan. Soon after, a representative from the office visited him in person and warmly welcomed his decision to go to Yan’an. On December 27, Shen held a meeting with Qian Zhiguang, the head of the liaison office, to discuss joining the resistance in Yan’an. They agreed that the machines would be loaned to the Communist Party free of charge and would be returned after the war. If the original equipment could not be returned, compensation of equal value in currency would be provided. All expenses related to transporting the machines and personnel would be covered by the liaison office.

On December 28, Shen wrote to the board of directors of Liyong Factory in Shanghai, reporting on the agreement. In his letter, he expressed his unwavering commitment to the country, saying, “The nation has reached the brink of danger. As long as we live, we must not stand idly by.” He emphasized that the Eighth Route Army was “willing to transport the equipment to Shaanxi unconditionally, as long as the machines are put to good use, contributing a little more strength to the country.” He sought the shareholders’ opinions on the matter. The board quickly responded via telegram, stating that “national interest comes first,” and gave full approval for relocating both personnel and equipment to Shaanxi, authorizing Shen to act with full discretion.

At the end of 1937, Shen Hong, along with his apprentice and six other volunteers, set off for Shaanxi with ten pieces of machinery. They split into two groups—one group, led by his senior apprentice Chen Xiaoliang, escorted the equipment by truck, while Shen led the other group by train. At that time, all supplies entering the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia border region were subject to strict inspection by the Kuomintang, and transportation schedules were uncertain, requiring patience.

In the early morning hours of January 31, 1938—Lunar New Year’s Eve—amid heavy snowfall and in total darkness, five trucks sent from Yan’an quietly left Xi’an, carrying Shen and his team along with the machines. After five grueling days, they finally arrived in Yan’an on February 4, the fifth day of the Lunar New Year. Liyong Hardware Factory became the only factory from Shanghai to be relocated to the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia border region at that time.

At the time, Yan’an was suffering from severe shortages of food and clothing, and its machinery manufacturing industry was virtually nonexistent. The equipment Shen Hong brought with him to Yan’an included more than ten machine tools such as lathes, drill presses, milling machines, and planers. In addition, he brought nine sets of equipment including electric motors and engines, 194 pieces of tools covering 47 types such as micrometers, 131 drill bits, other assorted instruments, as well as 18 technical books, including the Encyclopedia of Chemical Industry.

Though these machines and tools may have seemed ordinary elsewhere, they were extremely valuable to the besieged Yan’an because they included the “mother machines” necessary to manufacture other machinery—a critical foundation for developing an industrial base.

On February 6, 1938, just three days after Shen Hong arrived in Yan’an, the Central Military Commission reorganized the Military Industry Bureau, appointing Teng Daiyuan as its director. Soon after, the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border Region Machinery Factory was established, with Shen Hong serving as the factory’s chief engineer.

In March 1949, Shen Hong joined the newly liberated city of Beiping (now Beijing) with the Industrial Department of the North China People’s Government. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, he held key positions as Vice Minister in several ministries, including the Ministry of Electrical Machinery Manufacturing, the Ministry of Coal Industry, the Ministry of Agricultural Machinery, and the First Ministry of Machine-Building Industry.

The implementation of the First Five-Year Plan laid the industrial foundation of the new China. As economic construction accelerated, both civilian and defense industries urgently needed large-scale forgings. However, the few small and medium-sized hydraulic presses available domestically at the time were far from capable of producing large forgings, forcing China to rely heavily on imports to meet its development needs.

On May 22, 1958, as a delegate to the Eighth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Shen Hong wrote a letter to Chairman Mao Zedong, volunteering with determination: “China should have several 10,000-ton hydraulic presses distributed across major industrial zones… If Shanghai is willing to take on the task, I am ready to participate.”

After receiving the letter, Mao Zedong immediately forwarded it to Deng Xiaoping with the instruction: “Comrade Xiaoping: Please print and distribute this document to all comrades at the congress.” Mao also personally asked the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee leaders: “Can Shanghai do it? Is it willing to do it?” Upon receiving their affirmative response, the Central Economic Group swiftly convened a meeting and decided to form a design team for the 10,000-ton hydraulic press, appointing Shen Hong as the chief designer to lead the design and manufacturing efforts in Shanghai.

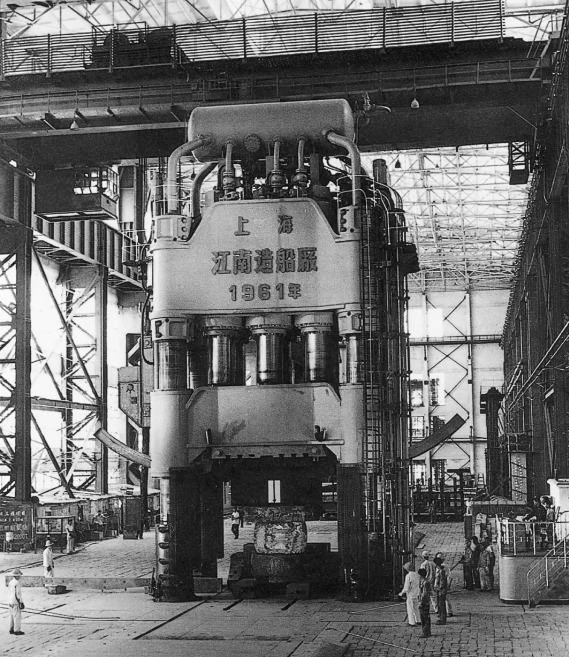

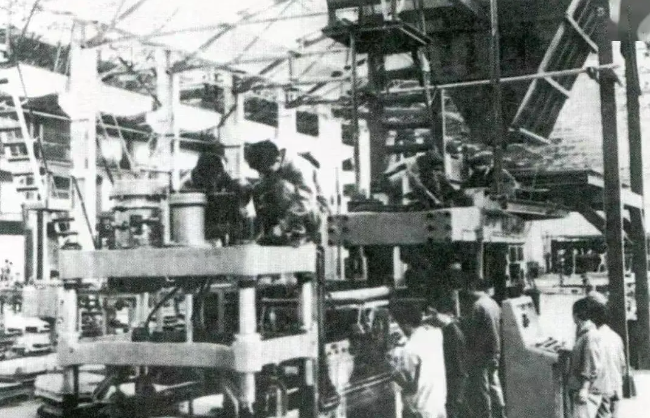

Shen Hong led a team of young designers to Jiangnan Shipyard, relying closely on the expertise and ingenuity of skilled workers to overcome one technical challenge after another. They began by designing and building a 120-ton simulation hydraulic press, and adopted a welded steel “bamboo-joint” structure to resolve the welding difficulties of assembling large cast and forged components. Innovative methods such as “ants gnawing bones,” “ants lifting Mount Tai,” and “silver threads crossing Kunlun” were invented to tackle the challenges of cutting, lifting, and flipping massive crossbeams.

On December 8, 1961, all 46,000 components of the 10,000-ton hydraulic press were completed, and the team spent two more months on installation. On June 22, 1962, China’s first 10,000-ton hydraulic press—designed and manufactured entirely domestically—was successfully installed. It became the world’s lightest and shortest 10,000-ton press by self-weight and height. Its success not only filled a major gap in China’s heavy machinery industry but also achieved a remarkable “three-in-one” functionality: capable of open-die forging, die forging, and punching—all in one machine, a feat unmatched by any other 10,000-ton press in the world at the time.

In the 1960s, China’s national economy faced severe difficulties. The complete withdrawal of Soviet technical experts further disrupted many ongoing construction projects. To revitalize the economy—especially the national defense industry—the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China decided to pursue independent development and launched a plan to design and produce nine sets of large-scale integrated equipment. These nine sets involved over 1,400 individual units across 840 types, with a total weight of 45,000 tons, and were manufactured by hundreds of units across the country.

At the time, Shen Hong, who was overseeing the installation of the 10,000-ton hydraulic press in Shanghai as Vice Minister of the Ministry of Agricultural Machinery, was reassigned as a member of the Party Leadership Group and Vice Minister of the First Ministry of Machinery Industry. He was tasked with leading the development of the nine major equipment systems. After years of effort, these massive machines were gradually put into operation, laying a solid foundation for China’s heavy machinery manufacturing industry and making significant contributions to its development.

Around the same time, the construction of the Sanmenxia Hydropower Station encountered major technical hurdles. Shen Hong was assigned to tackle the challenge. He developed solutions, organized resources, and overcame key obstacles in the welding of the large turbine rotor, ensuring successful installation and power generation. In addition, he participated in establishing the Ma’anshan train wheel rim factory to solve the problem of replacing worn wheel rims for locomotives. He was also involved in the “Third Front” construction campaign, leading the complete equipment design for the Panzhihua Iron and Steel Base and pioneering the “comprehensive balance” approach to large-scale industrial projects. During the construction of the 1,700mm hot strip rolling mill at Benxi Iron and Steel, he demonstrated a strong emphasis on independent innovation.

In 1981, during the commissioning of the Gezhouba hydropower units, repeated bearing overheating and wear incidents occurred. Some members of the acceptance committee believed that the units would never start. Minister of Water Resources Qian Zhengying turned to Shen Hong for help. Under Shen’s guidance and after more than a month of repeated testing and technical modifications, the units finally succeeded on the 16th startup attempt.

Qian Zhengying later wrote in her memoir: “In the end, Gezhouba was completed with two 170 MW units and nineteen 125 MW units, making it the world’s largest low-head hydropower station with a total installed capacity of 2,715 MW, as well as home to the world’s largest Kaplan turbine units. These units have now been operating safely for over 25 years. The credit for this independent innovation should first and foremost go to Comrade Shen Hong.”

Shen Hong led his team to achieve one major scientific and technological breakthrough after another and was honored as a true “Master Craftsman of a Great Nation.” In 1980, he was elected as a founding member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences—remarkably, the only academician in the Academy without a formal academic degree.