In the bustling neighborhoods of 1970s and 1980s Shanghai, amid the clatter of bicycles and the occasional honk of a city bus, there rumbled a curious contraption that became an unforgettable symbol of the era: the “Wugui Che” , or “Tortoise Tricycle.” Though its speed was modest and its appearance unassuming, it carried on its back not just passengers and goods, but also the aspirations, struggles, and daily rhythms of a changing city.

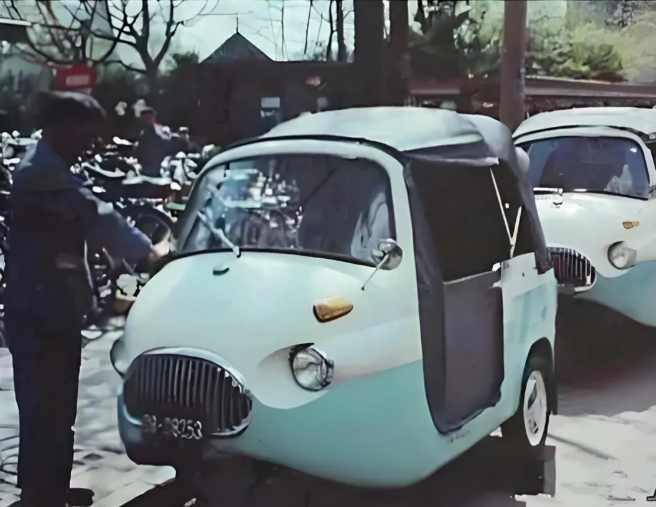

The Tortoise Tricycle was officially a simple three-wheeled motor vehicle, developed and produced by the Shanghai Bicycle Factory starting in the early 1970s. Powered by a small-displacement gasoline engine, typically around 125cc, and manually kick-started, it represented one of the earliest efforts in China to provide mechanized urban transport on a mass scale. Unlike the open-frame cargo tricycles of earlier decades, the Wugui Che had a fully enclosed metal shell. Its round, bulbous design—both protective and quaint—evoked the shape of a turtle, thus earning its nickname.

Functionally, the vehicle was built for maximum utility. It had a pair of front wheels and a single driven rear wheel, giving it stability while maintaining maneuverability on Shanghai’s narrow and uneven streets. The interior featured a small bench that could seat two or three people, and a cargo compartment large enough to carry everything from produce to spare parts. The presence of a windshield, complete with a working wiper, marked a rare touch of sophistication for working-class transport in those days. More importantly, it offered protection against the city’s capricious weather—a crucial advantage during Shanghai’s infamous rainy season.

But beyond the hardware, the Tortoise Tricycle earned its place in local memory through its sheer reliability. In a time when personal cars were virtually nonexistent and public transport was overcrowded and unpredictable, this three-wheeled underdog stepped in as a multipurpose workhorse. It was used by small-scale merchants, traveling doctors, rural peddlers, and urban families alike. It ferried children to school, brought brides to weddings, and served as mobile storefronts for vendors of tofu, noodles, or textiles. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was indispensable.

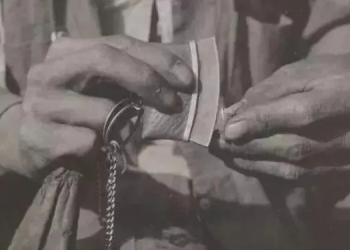

The affection that Shanghai residents still hold for the Wugui Che is rooted in the emotional landscape of that era. It was a time when every household had to stretch its resources, when self-repair and improvisation were daily habits. The vehicle’s design was straightforward enough that many owners became their own mechanics. A flat tire didn’t mean a visit to the shop—it meant pulling out a hand pump and a tire patch kit. Fuel scarcity meant creativity: many learned to adjust carburetors, clean spark plugs, or even fabricate parts. These qualities fostered a kind of mechanical intimacy, a sense that the machine was not just a tool, but a member of the household.

And yet, despite its popularity, the Tortoise Tricycle never enjoyed official prestige. It was never featured in advertisements or glorified in propaganda posters. It was the quiet engine of the everyday, performing humble miracles in alleys and intersections far from the eyes of policy makers. In this way, it paralleled the lives of the people it served—modest, resilient, and unheralded.

As Shanghai entered the 1990s and China’s economic reforms accelerated, the landscape began to change. The rise of scooters, compact cars, and public infrastructure gradually pushed the Wugui Che off the roads. Environmental regulations, rising fuel costs, and modernization campaigns rendered these vehicles obsolete. By the early 2000s, they had virtually disappeared from circulation.

But not from memory. A new generation of collectors and urban historians has begun to recognize the cultural and mechanical significance of the Tortoise Tricycle. Restored models occasionally appear at vintage fairs or local museums. Online forums host passionate discussions about engine models, restoration techniques, and regional variants. In art and photography, the image of the Wugui Che rolling past red-brick shikumen or parked in a misty alleyway now symbolizes a vanished world—one where life moved slower but with deeper texture.

At 7090.top, where we chronicle the overlooked innovations and daily artifacts of 20th-century China, the Wugui Che stands out as a case study in working-class ingenuity and adaptive urban design. It wasn’t made for luxury or prestige. It wasn’t sleek or stylish. But it met the needs of its time with honesty and grit. It was Shanghai’s turtle—slow, steady, and unforgettable.

In the end, the Tortoise Tricycle reminds us that not all revolutions come with noise. Some roll in quietly, three wheels at a time, leaving behind not skid marks but the warmth of lived stories.