Thirty-six years ago, a name unknown to the public suddenly made headlines across nearly every major media outlet in China.

On July 29, 1986, Deng Jiaxian passed away in Beijing at the age of 62.

Before this, both his name and the work he dedicated his life to were classified as top-level state secrets.

He was the chief theoretical architect behind China’s first atomic bomb and first hydrogen bomb — hailed as the “Father of Two Bombs.”

A hero we must never forget.The overwhelming majority of people had never heard his name until just one month before his death. But how many truly understand the greatness of his 62-year life? How monumental his journey was?

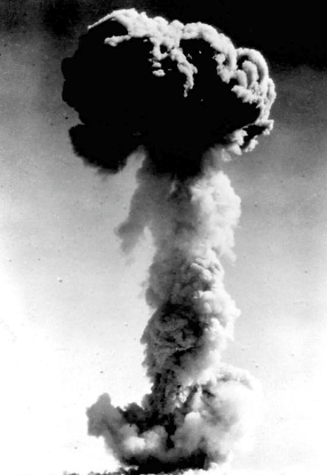

On October 16, 1964, China successfully tested its first atomic bomb.

On June 17, 1967, the first hydrogen bomb detonated in the skies above Lop Nur.

From the first atomic explosion to the hydrogen bomb, it took the United States over 7 years, France more than 8 years, and the Soviet Union a little over 4 years.

China achieved it in just two years and eight months.In May 1986, when Yang Zhenning (Chen-Ning Yang) specially visited Deng Jiaxian, he asked,“How much were you awarded after successfully developing the atomic bomb?”Deng replied,

“Ten yuan for the atomic bomb, ten yuan for the hydrogen bomb.”Upon hearing this, Yang Zhenning was overwhelmed with emotion and broke into tears.

In their final photo together, Deng Jiaxian — who never liked taking pictures — suddenly requested a photo.

Perhaps he already sensed something…

On September 13, 1979, during a live hydrogen bomb air-drop test, an unexpected incident occurred.

The parachute failed to deploy.

The hydrogen bomb plunged directly from the sky to the ground.

The command center immediately dispatched over a hundred chemical defense troops to search for the device.

Without an exact location, they scoured the vast Gobi Desert for hours, but came up empty-handed.

A nuclear weapon lying somewhere in China’s wilderness—any accident could result in catastrophic consequences.

In the midst of the emergency, Deng Jiaxian was burning with anxiety.

He insisted on joining the search.The base leadership tried to stop him, shouting:

“Old Deng, you can’t go! You must not go!”Deng replied,

“Then no one else should go either. I’ll go.”“You wouldn’t find it anyway, and you’d only be exposed to radiation for nothing.”Deng eventually tracked down the impact site.

With his own bare hands, he retrieved the broken bomb from the crater.

Upon returning, he said just one thing:

“It’s safe.”

In 1979, after recovering the unexploded nuclear warhead, Deng Jiaxian took a photo with Zhao Jingpu on the Gobi Desert at the Xinjiang nuclear test base.

From that incident, Deng suffered fatal radiation exposure.

Before leaving the site, despite never having taken work photos before, he pulled his colleague aside and took a commemorative photo.

After the photo, Deng muttered to himself in the returning car:“Do you know which part of the body plutonium is most easily absorbed by?”

He answered himself:“The bone marrow.”Then he said again,

“Do you know what the half-life is after it enters the human body?”“Two hundred years.”

From then on, Deng aged rapidly.Most of his hair turned white, and even routine tasks exhausted him.

On June 25, 1924, Deng Jiaxian was born into a well-known scholarly family in Huaining County, Anhui Province.

Just eight months after his birth, he followed his mother to Beijing, where his father was teaching at the time.

During his middle school years, Deng developed a growing passion for mathematics and physics. But just as he was immersed in his thirst for knowledge, the peaceful life of study was shattered by the iron hoofs of the Japanese invasion.

On July 29, 1937, Beiping (now Beijing) fell to Japanese forces. With every city they occupied, the Japanese would force civilians to participate in parades celebrating what they called their “victories.”

In October 1938, after the fall of Hankou in Hubei, the Japanese forced the citizens and students in Beiping to take to the streets, holding up Japanese flags in so-called celebratory parades.

That day, Deng Jiaxian, just 14 years old, could no longer tolerate the humiliation he felt. He tore a Japanese flag to shreds in public, threw it to the ground, and stomped on it furiously.

His teacher, witnessing the scene, feared for Deng’s safety—acts like this could easily lead to death under Japanese occupation. The teacher rushed to his father and pleaded,

“You must let the child leave Beiping as soon as possible!”

Left with no choice, Deng’s father arranged for his eldest daughter to accompany him southward to Kunming. Before he departed, his father gave him a simple but powerful instruction:

“Jia’er, in the future, you must study science… Science is useful for the country.”When Deng Jiaxian bid farewell to his younger brother, he said:“Right now, I have no tears—only hatred.”

After a long and arduous journey, they finally reached Kunming. His sister immediately enrolled him in the final year of high school at a school in Jiangjin, Sichuan.

One day, while walking along a mountain road by the Yangtze River, Japanese bombers appeared overhead. One bomb after another fell on nearby homes, flames and thick smoke rising into the air. Deng watched helplessly as the enemy ravaged Chinese soil, yet not a single bullet or cannon responded from the ground.

At that moment, he came to a chilling realization:

In a weak and humiliated nation, even in the remote rear, there is no true peace.

In the autumn of 1941, Deng Jiaxian was admitted to the Physics Department of the National Southwestern Associated University (commonly known as Xinan Lianda).

This university was a merger of three of China’s most prestigious institutions—Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Nankai University—relocated to Kunming during wartime. It was, at the time, the pinnacle of higher education in China.

The Physics Department at Xinan Lianda gathered many of China’s most distinguished physicists and professors, including Wu Youxun, Zhou Peiyuan, and Zhao Zhongyao. It also educated future giants like Yang Zhenning (Chen-Ning Yang), Li Zhengdao (Tsung-Dao Lee), and Zhu Guangya.

Yang Zhenning would later recall:“The physics I learned in Kunming was already at the highest level in the world at that time.”

The student dormitories at Xinan Lianda were rudimentary, to say the least. The rooms were drafty, meals were often mixed with sand, and Japanese bombers regularly launched air raids on the school.

Deng Jiaxian, once a carefree and handsome youth, became reserved and determined. He bottled up his frustrations and channeled all his energy into studying as if possessed by a fire from within.

In the summer of 1946, after graduating from the National Southwestern Associated University, Deng Jiaxian returned to Beiping (now Beijing), a city he had been away from for six long years. He took up a position as a teaching assistant at Peking University.

During this period, he met two people who would go on to play significant roles in his life. One was Xu Luxi, the woman who would later become his wife. The other was Yu Min, then a student in the physics department, who would later be hailed as “the father of China’s hydrogen bomb.”

Twenty years later, without ever having studied abroad, Yu Min would work alongside Deng Jiaxian and make monumental contributions to China’s hydrogen bomb project.

While teaching at Peking University, Deng was also preparing for his postgraduate studies in the United States. In 1947, he was accepted into the physics program at Purdue University. By the fall of 1948, he boarded a ship bound for the other side of the Pacific.

Before his departure, a close friend told him, “The dawn is about to break over China. Please stay and help rebuild the nation.”

Deng smiled and replied with conviction, “When the country needs me for its development, I will return.”

In 1949, Deng Jiaxian took a commemorative photo in Chicago with Yang Zhenning and Yang Zhenping.

During his studies in the United States, Deng pushed both his talent and diligence to the extreme. A Ph.D. program that typically took three years, he completed in just one year and eleven months, finishing all required credits.

Due to his outstanding performance, his professors recommended that he continue his studies in the United Kingdom. They believed he had a promising future and even hoped he might win a Nobel Prize one day.

But whether to continue conducting his beloved research in an already developed nation, or to return to a poor and newly established China and live a hard life—Deng never hesitated or made such a comparison.

On August 20, 1950, at age 26, Deng Jiaxian officially received his doctoral degree. The U.S. government tried to entice him to stay, offering superior research and living conditions. His professors and classmates also urged him to remain.

But Deng rejected them all.

His heart longed only to return to his motherland on the other side of the ocean.

On August 29, 1950, just nine days after receiving his doctorate, Deng boarded the SS President Wilson and set sail home without delay.

Deng Jiaxian and nearly a hundred other Chinese students who had completed their studies in the United States gathered for a group photo on the deck of the ship as they returned to their homeland.

That day, it had only been nine days since Deng received his doctoral degree.

Just nine days—and he fulfilled the promise he made two years earlier when he left China:

“When I finish my studies, I will return.”

After returning to China, someone asked him what he had brought back.

He replied, “A few pairs of nylon socks for my father—since they’re not produced in China yet.

And a head full of knowledge about nuclear physics: atomic nuclei, neutrons, protons, fission, fusion, deuterium, and heavy water.”

At the time, few people could have foreseen how critical that “head full of nuclear knowledge” would become—just eight years later—in launching China’s own atomic and hydrogen bomb programs.

At that time, the newly founded People’s Republic of China had just shaken off a century of humiliation, yet the shadow of nuclear threat loomed constantly overhead.

In fact, global opinion held that after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, no other nation faced a nuclear threat as directly and persistently as China.

After returning to China, Deng Jiaxian joined the Institute of Modern Physics under the Chinese Academy of Sciences as an assistant researcher.

From 1951 to 1958, over the course of eight years, he published multiple theoretical papers on nuclear physics, filling in gaps in China’s scientific understanding of the field.

He laid the groundwork for the theoretical development of nuclear physics in China, opening an entirely new chapter in this discipline.

Under the looming shadow of global nuclear deterrence, China was forced to make a strategic decision—to develop its own nuclear weapons.

On February 11, 1958, the Second Ministry of Machinery Industry (known as the “Second Ministry”) was officially established to oversee the nation’s nuclear industry and nuclear weapons development.

Qian Sanqiang was appointed as Deputy Minister.

But where could China find scientists capable of leading such a monumental undertaking?

Just as Qian Sanqiang was struggling with this question, Deng Jiaxian entered his field of vision…

He used only abacuses and slide rules to design an atomic bomb.

In August 1958, Qian Sanqiang called 34-year-old Deng Jiaxian into his office for a confidential conversation.

With a touch of humor, he said:“The country wants to light a big firecracker. Would you be willing to work on this project?”

Deng was stunned. It was clear: China was going to build an atomic bomb.Soon after, the Second Ministry established the Nuclear Weapons Research Institute (Code Name: Ninth Institute) in Beijing.

Two research departments were formed—Deng was appointed head of the Theoretical Physics Department.

He led a team of freshly graduated university students and began China’s nuclear weapons theoretical research from scratch.

Deng Jiaxian treated the young university graduates like younger siblings.

He often shared his ration tickets with them so they could have a little more food.

At first, the students respectfully called him “Director Deng,” but he insisted repeatedly:“Just call me Old Deng!”

Colleagues who worked closely with Deng at the time recalled:“It was a common occurrence to rummage through his pockets for cigarettes or search his drawers for sweets and snacks.”

Behind this approachable and humble exterior lay an immense sense of responsibility and crushing pressure.

How to build an atomic bomb?

No one knew.

And due to strict confidentiality rules, all the stress, frustration, and anxiety had to be digested alone, in silence.

On the night he made the decision to take on this secret mission, Deng turned to his wife, Xu Luxi, and said:“I’m changing jobs. From now on, the household will rely on you. My life will be entirely devoted to this new work.”

Xu Luxi recalled:“He said it with firm conviction. He said, ‘If I succeed in this mission, then my life will have been worthwhile. Even if I die for it, it will be worth it.’”

From that moment, Deng Jiaxian was appointed Chief Theoretical Designer of China’s Atomic Bomb Project.He essentially vanished from public life.He never traveled abroad again.He never published another academic paper.He never gave a public lecture.Outside of the classified system, no oneknew where he worked or what exactly he was doing.By day, he disappeared from sight; by night, he would return home quietly—like a phantom.

In the early phase of China’s atomic bomb research, Deng Jiaxian’s team received assistance from Soviet experts.

However, just a few months later, Sino-Soviet relations broke down.

The Soviet Union withdrew all their experts, cutting off all technical support.The Soviets even declared:“The Chinese people won’t be able to build an atomic bomb in 20 years.”The CIA echoed that sentiment:“It’s impossible for the Chinese to develop nuclear weapons on their own.”

In a poor and underdeveloped China that had nothing—no infrastructure, no resources, no equipment—how could one talk about developing an atomic bomb?In the U.S., the team that developed the first atomic bomb included at least 14 Nobel Prize winners.

Meanwhile, Deng Jiaxian’s team consisted of a group of freshly graduated students.At that time, China’s nuclear project relied on abacuses, slipsticks (manual calculators), and the occasional hand-cranked computing device.

Sometimes they had to rely on just pen and paper to process massive amounts of data.

What they calculated were enormous figures, stacked high in bundles of paper stuffed into burlap sacks, filling entire rooms.

Every single figure had to be checked over and over again to ensure complete accuracy.

Calculating a single model required tens of thousands of data points.

If there was even one error, the entire model would collapse.

Deng Jiaxian’s theoretical group recalculated everything nine times, discarding the Soviet-provided nuclear parameters and determining their own correct values.

They solved the core problem that would determine the success or failure of China’s first atomic bomb test.

Later, mathematician Hua Luogeng described Deng’s solution as:“A synthesis of the world’s toughest mathematical problems.