“We have won!” “Long live China!”

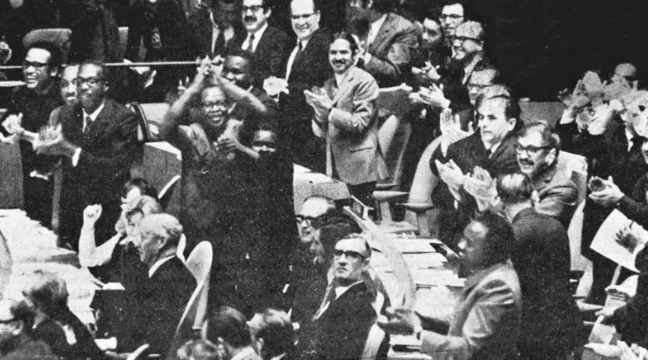

On the evening of October 25, 1971, the United Nations General Assembly hall erupted in thunderous applause. Delegates from numerous countries stood up to cheer, shake hands, embrace one another—some even broke into jubilant dances. The waves of celebration and shouts of joy seemed to go on endlessly.

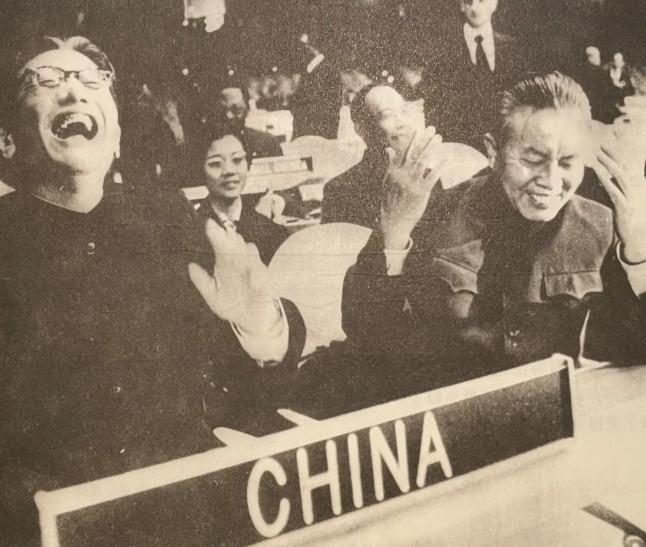

At that historic moment, Qiao Guanhua, head of the Chinese delegation and then Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, burst into unrestrained laughter as he looked up toward the sky. His face radiant with elation, this image was captured by photographers and became an enduring symbol of China’s diplomatic triumph in the 1970s.

That single frame immortalized not just the joy of one man, but the collective pride of a nation reclaiming its rightful place in the international community after decades of absence. The moment marked the passing of Resolution 2758, restoring the People’s Republic of China to its lawful seat at the United Nations and expelling the representatives of the former Kuomintang regime from Taiwan.

That night, delegates in the UN General Assembly hall—many of them—erupted in applause, handshakes, hugs, some even dancing. Their cheers of “We have triumphed!” and “Long live China!” echoed without cease.

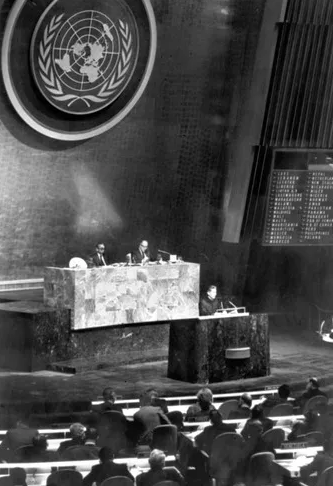

This was not just any vote. On October 25, 1971, at the 1976th session of the United Nations General Assembly, a sweeping resolution passed—76 votes in favor, 35 against, and 17 abstentions—adopted a proposal put forward by twenty-three nations, including Albania and Algeria, to “restore all the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations.” After two decades of exclusion, the PRC’s seats at the UN and the UN Security Council were reinstated, and representatives of the Kuomintang regime on Taiwan were immediately expelled from all UN bodies.

This was not only a victory for China’s diplomacy—it was a triumph for justice, for all peoples of the world, and for every nation that upheld righteousness.

Memories leave indelible marks. Despite now being nearly ninety years old, Ye Zhixiong, a Xinhua News Agency correspondent, still vividly recalls each moment when, as a member of the Chinese delegation, he attended the UN General Assembly for the first time 55 years ago. “Many scenes are like watching a movie from yesterday,” he said.

Today, this veteran journalist remains vigorous and full of drive. He said, “The United Nations reflects the world’s development. China’s restoration to its lawful UN seat was, in that year, the paramount event for China, the world, and the UN.”

On the evening of October 25, 1971 (Eastern US time), the 26th UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2758, restoring the People’s Republic of China’s legitimate seat at the UN. On the 26th, then UN Secretary-General U Thant sent a telegram inviting the Chinese government to dispatch a delegation to the General Assembly. And on the 29th, the Chinese government officially announced: We will attend!

At that time, Ye Zhixiong had been scheduled to go to Africa as a permanent correspondent, but his plans were abruptly changed. Not long after, his new mission was revealed—he, photographer Qian Sijie, and communications officer Zhu Xingquan were assigned to accompany the Chinese delegation to the UN. Ye was the only press correspondent in the delegation.

On the evening of November 5, Premier Zhou Enlai received members of the UN delegation at Zhongnanhai. Though tired, he still looked radiant and alert. He reviewed each of the 52 delegation members, speaking with them one by one. When his turn came, Premier Zhou asked Ye about where he had been stationed and whether he was confident in the assignment. Ye replied: “Absolutely confident—I will do my job well!” When Zhou asked if anyone had been left out, someone quietly mentioned that a Xinhua reporter hadn’t been asked. Zhou responded immediately: “He was just asked.”

Soon, November 9 arrived—the day the delegation departed. Ye remembered that over 4,000 people from all walks of life in Beijing, along with more than 60 foreign diplomats stationed in China, turned out to send them off at the airport. The delegation first flew from Beijing to Shanghai, then connected via Air France through Yangon, Karachi, Athens, Cairo, and Paris, before finally arriving at UN Headquarters in New York at midday local time on November 11.

The trip to New York became historic. Ye’s strongest impression? The “China fever.” When their plane landed, awaiting them at the airport were representatives from friendly countries, UN staff, Chinese diaspora, and journalists—hundreds formed a welcoming crowd. On the way to the Roosevelt Hotel, well-wishers crowded the streets, waving and offering friendly greetings. Many flashed V-signs for “victory.”

Once settled in New York, visitors frequently approached Ye to chat with this reporter representing New China. A memorable moment came when UNGA President Malik invited several prominent international media figures to lunch, and Ye was honored as a guest of distinction. These were veteran correspondents at the UN—some with white hair. This warm “Chinese wind” swept across New York City: a Hunan restaurant near the UN saw long queues; Macy’s ran ads for Zhongshan suits (Mao jackets); other stores set up “China counters”; schools hosted “China Day” or “China Week”; students competing in Model UN bristled with pride at representing China.

On November 15, 1971, at 10:15 a.m. Eastern US time, members of the Chinese delegation walked into the UN Assembly Hall amid thunderous applause—taking their first seats labeled “CHINA.”

Ye recalled that while a few representatives were asked to give welcome speeches on behalf of world regions, many other delegates spontaneously spoke to express their welcome, turning that session into a warm celebration of China’s return.

That same day, at the 26th UN General Assembly, Sami Baholli, Albania’s Permanent Representative, delivered a welcome speech to the Chinese delegation. Ye was particularly struck when the Hungarian delegate even spoke a few sentences in Chinese, while the Chilean delegate passionately recited a poem by Mao Zedong: “Mountains rise overhead; red flags blow past the Great Pass.”

To Ye, these words weren’t merely expressions of friendship—they reflected global attitudes toward China and perspectives on world affairs in that moment.

During the Assembly that day, Qiao Guanhua, head of the Chinese delegation, delivered a powerful speech on behalf of the Government of the People’s Republic of China. The highlight was his comprehensive articulation of China’s principled positions on major international issues. He emphasized: “We assert that issues in any country must be handled by its own people; global affairs by all nations; UN affairs by all UN members, not dominated or monopolized by great powers.”

Ye recalled: “He spoke neither submissively nor arrogantly—his reasoning was firm, eloquent, and gracefully delivered.” After the speech concluded, delegates from more than thirty countries lined up to shake his hand and offer congratulations.

Ye’s records show the session continued well beyond the scheduled time; it finally concluded at 6:40 p.m..

He reflected that accompanying the delegation to the UN was akin to a “mortal firefight.” Reporting such historic events was his first—he had to relay the real-time situation to China and the world, while simultaneously transmitting highlights of speeches back home. He felt the weight of responsibility acutely: “As a journalist for New China, I had to fight this battle well!”

Thanks to his five-year tenure in London, Ye had developed a “single-reporter combat ability.” He told the press later that his stay at the UN had two keys to success: “struggle” and “making friends.”

For over 50 days, Ye slept just three to four hours a night, reporting across UNGA, Security Council, and six UNGA committees—sometimes simultaneously in eight session rooms! He watched, asked, and quickly discerned the UN’s rhythms. Through friendly relations with Secretariat staff, he could cover multiple meetings alone.

In breaking news, he began writing before sessions ended; he took advantage of daily lunchtime press briefings for story leads; he “picked up” speeches and materials from the Secretariat’s translation, Chinese, and document divisions; and he collaborated with UN Newspaper correspondents for research.

Over three years as a UN correspondent, Ye covered three sessions of the General Assembly, producing many English-language reports—voicing China’s presence on the world stage.

After 1972, Xinhua steadily expanded its UN bureau. From a tiny office barely housing three desks, they moved to a larger room overlooking the East River. By 2023, 55 years since China regained its UN seat, the nation’s rejuvenation and global recognition have soared, and the UN’s role has strengthened significantly. “Upholding the UN-centered international system and Charter-based international relations remains vital in resisting hegemony, defending multilateralism, and advancing global peace and development.” Ye reflected.

Looking back on that era, Ye said with quiet pride: “I am deeply honored to have lived through that chapter—and more proud of my motherland.”