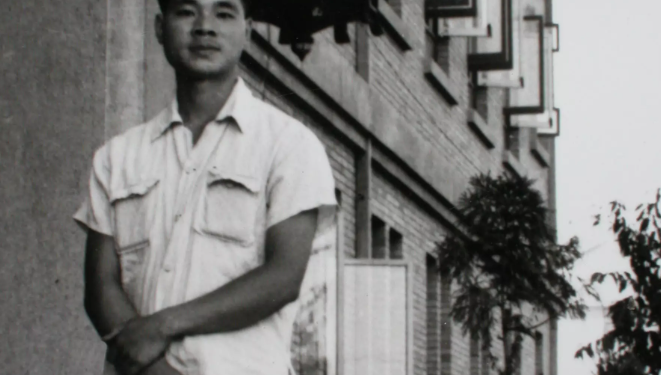

In the heart of Xiangxiang’s old town lies Nanzheng Street—an ancient road steeped in a thousand years of cultural heritage. It was from here that one remarkable individual emerged, whose life would be etched forever into the annals of the People’s Republic of China. His name—Luo Jianfu —shines as a symbol of selfless dedication, and his story has been recorded in the official Brief History of the Communist Party of China.

More than 30 years ago, while attending Xiangxiang No.3 High School, I happened to be taught by Luo Jianfu’s younger brother, who served as our geography teacher. Between classes, in the white chalk dust drifting across the blackboard, bits and pieces of Luo Jianfu’s life would occasionally surface in conversation. Slowly, a clear image began to form—a man of unmatched integrity and relentless scientific spirit. And now, as my fingers brush once more across the yellowed pages of history, his story, refined by time, burns brightly like stars against the night sky of a new era.

Today, when we stand in awe of Longcheng—the millennia-old city that nurtured countless heroes—we remember Luo Jianfu not merely as a symbol of honor but as a spiritual beacon that transcends time. His unwavering loyalty to the nation mirrors the pulse of the land nourished by the Lianshui River, where the heart of a patriot always resonates with the destiny of his country.

Luo Jianfu was a scientist of the 20th century, whose greatest achievement was the development of China’s first graphic generator—an automatic computer-controlled image-setter, once indispensable to the nation’s aerospace and electronics industries.

At that time, China had no such technology, and foreign nations had tightly controlled the export of such equipment. The graphic generator was considered a “strategic banned item” under Western export restrictions. Luo Jianfu had never even seen a prototype. Yet, when called upon by the nation to bridge this critical technological gap, he accepted without hesitation.

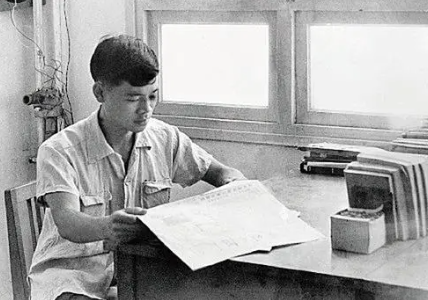

To accelerate development, Luo Jianfu spent his days and nights locked inside his lab. When hunger struck, he gnawed on plain steamed buns. When exhaustion overwhelmed him, he would nap on the cold floor. These were not temporary sacrifices but a lifestyle rooted in purpose.

This was during the Cultural Revolution, a period when academic and scientific pursuits were heavily disrupted. Originally trained in nuclear physics, Luo Jianfu tenaciously self-studied subjects critical to his new mission: automatic control systems, applied mathematics, and integrated circuits. It was then that he forged an unbreakable bond with science and technology.

In 1965, Luo shifted his focus to microelectronics, pioneering the field of graphic generator development in China. Faced with severe international technological blockades, he took it upon himself to master interdisciplinary knowledge: from electronic circuitry to precision mechanics. He even taught himself to read complex German technical documents, often studying through the night. His unyielding will shattered the boundaries of conventional learning.

In 1972, Luo Jianfu successfully developed China’s first-ever graphic generator, effectively ending the country’s dependence on foreign image-setting technology in aerospace.

Three years later, in 1975, he completed the more advanced “Type II Graphic Generator,” which greatly enhanced the nation’s aerospace capabilities. His work earned a National Science Conference Award. Yet, when submitting the project for recognition, Luo humbly listed his colleagues as co-creators and placed his own name last.

He twice passed up the opportunity to apply for senior professional titles—in both 1980 and 1981—explaining simply, “I still have room to grow.” His philosophy in life was one of humility and simplicity: he often subsisted on steamed buns, slept on bare floors, and spent his research stipends entirely on books and instruments.

Just as he was sprinting toward the completion of the “Type III Graphic Generator,” Luo was diagnosed with a highly aggressive form of cancer—poorly differentiated malignant lymphoma, one of the most difficult cancers to treat.

Despite this, Luo refused expensive medications and remained at his desk, revising technical drawings until the very end. As he lay on his deathbed, he made one final request to his doctors: “Please dissect my body—it might contribute something to medical research.”

Luo Jianfu passed away at the age of 47. The final pages of his blueprints, soaked with sweat and effort, still retained traces of body heat. Though his life ended in the laboratory, the legacy he left behind has long outlived him.

In 2019, Luo was posthumously awarded the title of “Most Beautiful Striver”. His contributions are officially documented in the Brief History of the Communist Party of China. On page 252, the record reads:

“Luo Jianfu of the 771st Research Institute under the Ministry of Aerospace Industry, remained indifferent to fame and fortune, dared to take on scientific challenges, and made tremendous contributions to China’s aerospace industry. He is widely known as ‘China’s Pavel Korchagin’.”

This reference likens Luo to the heroic Soviet character Pavel Korchagin, famed for his tenacity, sacrifice, and revolutionary ideals.

Luo Jianfu’s story is not just one of scientific achievement. It is the story of a man who, through resilience and quiet heroism, defined what it means to live for something greater than oneself.

In an era when China was isolated technologically and politically, he became the tip of the spear, challenging the impossible. His commitment to national development, to public service, and to ethical humility, remains a model for all generations of scientists and citizens alike.

From the red-brick alleys of Nanzheng Street to the high-tech labs of national defense, Luo’s journey tells us that greatness lies not in the applause of others, but in silent, unrelenting pursuit of excellence.

He did not live to see the future he helped build—but the future remembers him.