1982 was a pivotal year in China’s reform and opening-up.

At the 12th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Deng Xiaoping proposed embarking on the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics. In general terms, this moment is regarded as the starting point of that road. At the same congress, then-General Secretary Hu Yaobang introduced the “Fourfold Increase” target—doubling the gross output value of industry and agriculture by the end of the 20th century. This was a highly significant goal in China’s reform process.

Around this development objective, Shanghai’s growth strategy began to shift. Starting in 1978, the city launched an industrial renovation and revitalization study project. The original intent of this project was not to alter the city’s development trajectory, but rather to explore ways to further expand industrial

production. With the Party’s national focus redirected toward economic development, Shanghai—China’s largest industrial base—sought to make greater contributions to the nation by producing more industrial goods to meet public needs. The investigation, which lasted three years, eventually moved beyond its initial purpose, becoming instead a reflection on and reconsideration of Shanghai’s long-term development strategy.

The study reached a fundamental conclusion: under the Party’s “Fourfold Increase” target, Shanghai would face enormous difficulties. To double its industrial and agricultural output by century’s end, two basic conditions had to be met: first, raw material supplies from across the country needed to double, since Shanghai’s production inputs were strictly allocated by national planning; second, the scale of Shanghai’s industrial enterprises needed to double as well. In reality, neither condition was feasible. National allocations of raw materials to Shanghai had already declined from 100% to about 40%, and the city’s industrial capacity—concentrated within 150 square kilometers of the central district—had already been stretched to its limits.

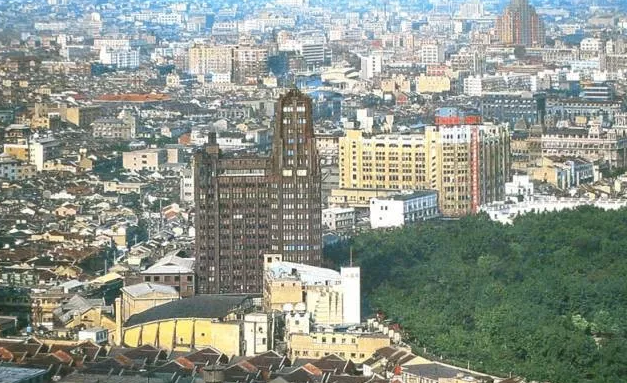

At the time, two phrases captured the dilemma: “high-rise factories” and “street-side warehouses.” Many office towers in central Shanghai, including former financial buildings along the Bund, had been converted into factories; meanwhile, because storage space was insufficient, raw materials and products were often piled directly on the streets.

Thus, by the early 1980s, Shanghai’s industrial expansion had reached a ceiling. Its once-competitive products were losing their edge. A vivid metaphor described the situation: “Shanghai was using 1930s equipment and 1960s technology to produce 1980s goods.” In 1983, a telling event occurred: plastic sandals from Guangzhou were showcased at Shanghai’s iconic No.1 Department Store, where they proved more popular in both style and price than local products. This “northward flow of Guangzhou goods” delivered a strong shock to Shanghai’s consumer market.

Consequently, following the traditional path of development, Shanghai could not possibly achieve the “Fourfold Increase.” This realization sparked the famous debate: “Where should Shanghai go?”

The answer pointed toward a dramatic shift: Shanghai needed to develop the “tertiary sector” to strengthen its role as an economic hub, while phasing out industries and products with poor efficiency and little potential. Significantly, this was the first time the concept of the “tertiary industry” entered mainland China’s policy discourse. Traditionally, only industry and agriculture were considered contributors to total output, while services were dismissed as non-productive. Shanghai policymakers, however, argued that a true multifunctional metropolitan center required strong emphasis on services and trade; otherwise, the city’s central role could not be realized. As a result, Shanghai became the first city in China to introduce official statistics on the tertiary sector.

In 1980, Shanghai began drafting its own urban plan. In 1986, two strategic workshops produced four proposals: northward expansion, southward expansion, westward expansion, and eastward expansion. Later that year, the State Council approved a general development framework, highlighting the need to

strengthen the northern Baoshan (with Baosteel) and southern Jinshan (with petrochemicals) industrial zones, while also accelerating new district construction. Importantly, the State Council explicitly mentioned Pudong, urging planned development of infrastructure such as bridges and tunnels across the Huangpu River, and calling for Pudong to grow into a modern district with finance, trade, technology, culture, education, commerce, and residential facilities.

China’s reform was characterized by gradual, step-by-step progress. Although the 1980s are often remembered as a period when Shanghai lagged behind the southern Special Economic Zones, in reality, the city undertook wide-ranging reforms that laid crucial groundwork for the breakthroughs of the 1990s.

First, breaking through the planned economy. Though Pudong’s official opening began in 1992, many of Shanghai’s experiments in the 1980s paved the way. Reforms advanced across enterprises, markets, government functions, and social security—establishing a foundation for the city’s rapid growth in the next decade. From 1982, over 2,000 state-owned enterprises underwent restructuring, adopting new responsibility systems; in 1984, factory director responsibility systems were introduced; in 1986, administrative corporations were reformed and labor contract systems introduced; by 1987, comprehensive contracting systems were in place.

Second, land reform. In August 1988, Shanghai auctioned Lot 26 in the Hongqiao Economic and Technological Development Zone through international bidding. Covering 1.29 hectares, it was successfully leased to a Japanese company for $28.05 million, with a 50-year land-use right. Though modest in scale, the event had groundbreaking significance—it marked China’s first land-leasing transaction conducted to international standards, signaling determination to deepen reform. This experience directly influenced later land policies, including those of Pudong.

Third, expanding openness. In 1981, Shanghai Trust and Investment Company was founded; in 1986, it issued ¥25 billion Samurai bonds in Japan. Throughout the decade, new economic and technological zones were established—Minhang (1983), Hongqiao (1984), Caohejing (1988)—each with distinctive orientations such as foreign trade, export-driven growth, or high technology. In 1986, the State Council approved a $3.2 billion foreign investment program for Shanghai. These initiatives positioned the city as an important testing ground for China’s opening.

The official launch of Pudong development in April 1990 was a watershed moment. Its political significance was immense, symbolizing a new stage in China’s reform:Great achievements. Pudong was not just a local project but a national strategy, envisioned by Deng Xiaoping as a shortcut to revitalizing Shanghai and driving the Yangtze River Delta as well as the broader Yangtze Basin.High starting point. Pudong was conceived not as a simple replica of coastal Special Economic Zones, but as a new district with comprehensive openness—covering markets, finance, enterprise systems, and modern infrastructure.Short timeframe. Its rapid implementation marked the speed and ambition of China’s reform in the new era.

Based on this judgment, we can draw a basic conclusion that the success of Pudong’s development and opening up is not the product of “policy airdrop”, nor is it driven by policies and projects. Instead, it is driven by institutional breakthroughs and innovations, and is the inevitable result of my country’s deepening reform and opening up.