In October 1978, the State Oceanic Administration submitted a report to the State Council entitled “Request to Initiate Antarctic Research.” Fang Yi, then Vice Premier, approved with the instruction: “Tentatively agree, make active preparations. But do not set things in stone; wait and see when the time comes.”

Yan Qide, who at the time worked at the State Oceanic Administration and later became deputy director of the Polar Research Institute of China, recalled to China Newsweek that the international situation then was pressing and left no time to lose.

In 1959, twelve nations including the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and Japan, all of which had already established research stations in Antarctica, signed the Antarctic Treaty in Washington. The treaty prohibited military activities and resource exploitation in Antarctica, while encouraging scientific research and international cooperation. Most importantly, the treaty froze territorial sovereignty in Antarctica: any national claims to Antarctic territory were neither recognized nor denied during the treaty’s validity. The treaty was set to expire in 1991, and whether it would be renewed or replaced with a new agreement, or whether resource exploitation would be opened, remained unpredictable.By the late 1970s, 18 nations had already established more than 40 permanent research stations and over 100 summer stations across Antarctica. Not only developed countries, but many developing countries had planted their flags on the Antarctic continent. In the Argentine and Chilean stations, several children had even been born, seemingly as a deliberate preparation for future territorial claims.

In May 1981, with the approval of the State Council, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Science and Technology Commission, and the State Oceanic Administration jointly established China’s first specialized body for Antarctic research: the National Antarctic Expedition Committee.

Guo Kun, who had been working in the Comprehensive Planning Division of the Department of Science and Technology of the State Oceanic Administration, was transferred to serve as director of the Committee Office. A graduate of the meteorology department of Harbin Military Engineering Institute, he had been engaged in military science and technology for many years.For Guo, this was an entirely new field with no prior experience. He did not even know what specific projects should be researched, and could only refer to reports in newspapers about what other countries were doing.

Yan Qide, then working at the State Oceanic Administration, was seconded to the Antarctic Office, where he drafted the detailed plan for China’s first Antarctic expedition. Guo Kun carefully revised the text, scrutinizing even punctuation marks. Yan recalled that Guo’s coordination and writing skills were outstanding, his considerations meticulous, and his vision forward-looking.Liu Xiaohan later remarked that Wu Heng and Guo Kun played pivotal roles in promoting the Antarctic program: “To put it bluntly, they were constantly running around, lobbying everywhere. The scientists emphasized scientific significance, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stressed diplomatic and political significance, while Guo and Wu gathered these arguments and presented them to the top leadership. By framing it strategically, they persuaded the central leaders to commit. In that sense, Guo was truly a strategist.”

In September 1983, Guo Kun and two other Chinese delegates traveled to Canberra, Australia, to attend the 12th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.

Under the treaty, there were Consultative Parties and Non-Consultative Parties. The Consultative Parties included the original twelve signatories as well as four countries that had subsequently established stations in Antarctica. China, which had not yet built a station, was one of the nine Non-Consultative Parties invited to participate, but it had no voting rights. Among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, China was the only one without a vote in Antarctic affairs.The conference agenda contained more than 30 items. Once substantial topics were raised, the gavel would strike, and all non-Consultative Party representatives were asked to leave the room to “have coffee.” Afterward, no one informed them of the progress or outcome. At 48 years old, Guo Kun realized that whether China established a station in Antarctica “was a matter of national honor and dignity.”

In February 1984, at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Zhu Kezhen Field Science Award ceremony, 32 scientists including Wang Fubao and Sun Honglie co-signed a letter to the Central Committee and the State Council under the title “March to Antarctica,” urging China to establish a research station on the continent.

Hu Qili, then Secretary of the Secretariat of the Central Committee, gave instructions: “Thirty-two scholars have jointly written to the Party Central Committee, suggesting that China should independently form an Antarctic expedition team. This matter is by no means simple.”

Yet there was also significant controversy. Cost estimates suggested 110 million yuan would be needed over ten years. Two months later, Hu Qili again commented: “If we neglect many underdeveloped regions at home but spend money to go all the way to Antarctica, people will certainly have differing opinions.” He urged that the matter be considered carefully.Li Peng, then Vice Premier, suggested that the State Oceanic Administration draw up a plan for building a station: “Secure a foothold, and keep costs under 20 million.” A senior State Council leader later added: “There was already a report two years ago, which I withheld approval of. But if it really requires only 20 million, then building an unmanned station is acceptable. Still, the calculations must be exact.”

Following these instructions, in May 1984 the National Antarctic Expedition Committee and the State Oceanic Administration began preparing a comprehensive plan for Antarctic research and station construction. Subsequently, Guo Kun accompanied Luo Yurou, then director of the State Oceanic Administration, three times to Li Peng’s office to report on preparations.

On June 25, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council officially approved the report on building China’s Great Wall Station in Antarctica. Li Peng wrote on the report confirming the departure time: “Anticipate greater difficulties, make thorough preparations, prioritize safety, secure a foothold, survive the winter, accumulate experience, and lay a solid foundation for the long-term Antarctic mission.”Guo Kun immediately began preparations to lead the team landing in Antarctica. He and the Committee members searched through libraries in Beijing but could not even find a complete map of Antarctica. Finally, they discovered a 1927 English edition of Annals of the Polar Regions at a used bookstall—this became their most important reference.

At that time, major Antarctic nations already owned several professional icebreakers, but China had none. After repeated discussions, it was decided to use China’s first domestically designed and built 10,000-ton oceanographic research vessel, Xiangyanghong 10, as a substitute. Though lacking icebreaking capability, it could withstand gale-force winds up to level 12.

With an average annual Antarctic temperature of minus 25°C and extreme lows near minus 90°C, the Chinese expedition members could not procure adequate polar gear on the market and had to design their own. The Shanghai Textile Science Research Institute developed new down-jacket fabric after numerous trials, and the Shanghai Down Garment Factory rushed to produce over a thousand down jackets and summer outfits. Tianjin’s Sports Shoe Factory, Greater China Rubber Factory, and Long March Shoe Factory developed summer footwear and cold-resistant boots. After more than four months of preparation, over 500 tons of supplies and scientific equipment—over a thousand types in total—were shipped to Shanghai.

In October 1984, the expedition team underwent training at Beijing Sports University. The program covered construction, rescue and survival, firefighting, learning the Antarctic Treaty, and physical conditioning.

Liu Xiaohan, who had just returned from studying in France and been assigned to the Institute of Geology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was asked by his supervisor whether he would like to join the Antarctic expedition. He immediately agreed and entered the training.There, he first met Guo Kun. He observed that Guo was sometimes very strict, yet at times quite amiable. When team members worked hard, Guo welcomed them with a smile; but if anyone shirked hardship or slacked off, he gave no face at all.

On October 13, 1984, Wan Li and Hu Qili met with members of China’s first Antarctic expedition team in the Great Hall of the People. Wan Li said: “This trip is an excellent beginning. We have no ambitions beyond gaining knowledge in this field.” Hu Qili emphasized ensuring safety and guaranteeing that the entire team would return victorious and unharmed. “In addition, you should be authorized: if any frontline member demonstrates exceptional performance and meets the requirements of Party membership, they may be admitted into the Communist Party.”

At 10:00 a.m. on November 20, 1984, China’s first Antarctic expeditionary fleet—consisting of 592 members (one disembarked mid-voyage)—set sail from the banks of the Huangpu River. Wearing sky-blue down jackets and caps emblazoned with the word “China,” they departed aboard the oceanographic research vessel Xiangyanghong 10 and the salvage vessel J121, heading to Antarctica in semi-military formation.

The overall expedition was commanded by Navy Rear Admiral Chen Dehong. It was divided into four units: the Antarctic land expedition team, the Southern Ocean expedition team, Xiangyanghong 10, and J121. Among these, the Antarctic land expedition team bore the most critical mission—constructing Great Wall Station on King George Island. Guo Kun served as team leader.Onboard the Xiangyanghong 10, Liu Xiaohan and other members had all signed “life and death pledges.” Large plastic bags were carried as body bags, in case of fatalities, with the intention of placing bodies in the ship’s cold storage.

Conditions on Xiangyanghong 10 were harsh. Several people squeezed into a small cabin; toilets were communal, dirty, and messy. Each person was allocated only one mug of fresh water per day, to be used for washing their face, brushing teeth, and wiping down their body.

On December 12, the two ships entered the “Roaring Forties,” also called the storm belt, an area perpetually battered by gale-force winds and waves over ten meters high. More than 60% of the team members became seasick. Some could not eat at all; others vomited whatever they managed to swallow. Crew members often fell from their bunks, and waves constantly crashed over the deck.

At night, the cold seeped through. The cabins were not insulated, and snow would drift in through the cracks. When they awoke the next morning, their sleeping bags were often covered with a layer of snow, and beneath their air mattresses lay puddles of melted water.

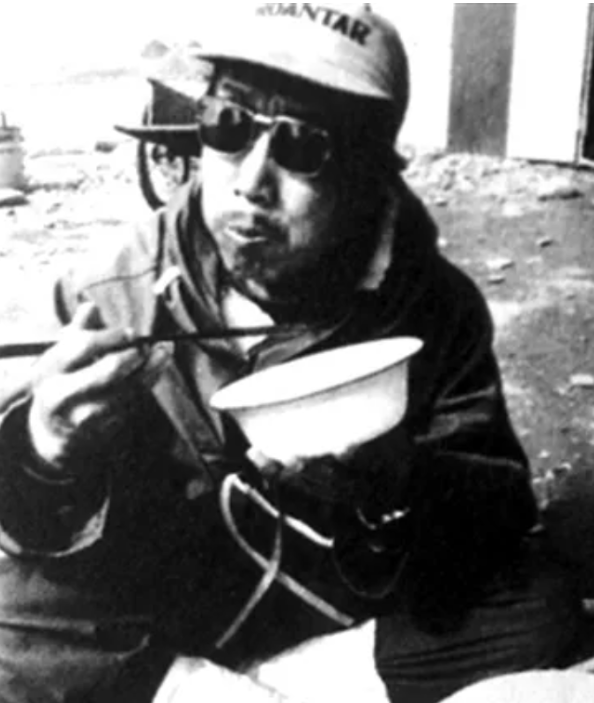

On January 7, 1985, Guo Kun and his team crossed the northern beach, climbed over rocky hills, and reached the Marsh Base in Chile to negotiate boundary issues. After negotiations, the matter was resolved peacefully. Team members recalled that during those days, “territory-grabbing” incidents occurred one after another.The permafrost in Antarctica was extremely hard; a pickaxe could only loosen a small amount of soil with each strike. To keep up with progress, team members slept only four hours a day. Every morning, Guo Kun would walk from tent to tent, unzip each sleeping bag, forcibly pull the person out, and shout, “Time to work!”

Without a dining hall, the team had to eat outside the tents; meals would freeze into ice before they were even finished. Washing and cleaning were done entirely in icy streams, or by rubbing with snow. Many people’s faces and ears were swollen from the cold.

The meteorological team reported the weather daily, and as soon as conditions improved even slightly, Guo Kun would immediately call everyone to work. Liu Xiaohan said that Guo Kun was a general of iron and blood, decisive and strict. If the foundation pits couldn’t be dug, they had to be completed within the set time. “Even if we were exhausted to the point of death, one look from him meant we had no choice but to push ourselves to the limit.”

Liu Xiaohan did not expect that most of the time in Antarctica would be spent constructing buildings. “Back then, there was no clear distinction between leaders and scientists; everyone was a construction worker, all on the front line, including Team Leader Guo Kun himself. We would jump into the freezing sea to repair the dock. After a whole day’s effort, we finally finished it, only to find the next day that sea ice had pushed it away, and we had to start over.”

Yan Qide said that Guo Kun meticulously organized and arranged every detail. During meetings, he would let everyone voice their opinions first and then fill in any gaps himself.

Forty-five days later, on February 14, China’s Antarctic Great Wall Station completed its final operation. The copper nameplate of the “Great Wall Station” was embedded directly above the door of the first building, symbolizing “the Great Wall extending to Antarctica.”

The main structure of the Great Wall Station consisted of six orange-red buildings, including a power station, communication station, meteorological station, surveying office, food storage, research building, medical and cultural building, dock, helicopter airfield, post office, and more than 20 other facilities.In front of the main building, the team erected a milestone sign—17,501.949 kilometers—the distance from the Great Wall Station to Beijing.

After the construction of the station was completed, Guo Kun allowed the team three days for field scientific research. This was also the first time China conducted independent scientific research relying solely on its own station.

On February 20, the first day of the Lunar New Year, the team held the inauguration ceremony of the Great Wall Station. Wu Heng, Director of the National Antarctic Research Committee, specially came from Beijing to preside over the opening. After the ceremony, a celebratory banquet was held in the dining hall. Guo Kun, moved with emotion, said, “Finally, we have not failed our mission,” and he began to cry as he spoke. All the men embraced each other and wept together.With the establishment of an independent Antarctic research station, on October 7 of the same year, at the 13th Consultative Party Meeting of the Antarctic Treaty held in Brussels, China officially became a Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty. From that point on, China gained the right to speak, vote, and exercise veto power in Antarctic international meetings.

Due to technical limitations, the Great Wall Station was built on King George Island. In terms of location, it was not within the Antarctic Circle, serving only as a foothold. Its remote location made travel inconvenient, whether coming from China or heading to the Antarctic interior. Moreover, the Antarctic Treaty was set to expire in 1991, and future developments were uncertain.

Four years after the completion of the Great Wall Station, Guo Kun, now appointed as the leader of the Antarctic research team, set out again to establish the Zhongshan Station in the Antarctic interior.

In November 1988, the vessel Polar Star set sail toward the Antarctic continent. On the night of January 14, 1989, it encountered a massive ice collapse. The fallen glacier was only two to three meters away from the ship. The entire crew entered an emergency state, and some even wrote farewell letters. Gordon Yi, the head of the meteorology group, told China Newsweek that this was the most dangerous situation during the station construction process.After the ice collapse passed, the Polar Star was surrounded by floating ice. The Soviet station chief referred to previous precedents, believing that the vessel might not be able to leave within that year. The expedition leaders reported the situation via encrypted telegram to the State Council, and State Councilor Song Jian instructed: “Ensure the safety of personnel.”

The team party committee decided on evacuation, standby, and beaching. Elderly and weak members were sent ashore, while core and young, strong members stayed on the ship. If the situation worsened, the Polar Star would have to take the risk of deliberately grounding on the shore to avoid sinking. After Guo Kun announced the decision, the atmosphere became even tenser.

On January 21, the floating ice that had trapped the Polar Star for seven days finally split open a 30-meter-wide channel. Based on reconnaissance reports, the fleet decisively set sail, breaking through the ice collapse area and reaching Zhongshan Harbor to unload cargo. Just two hours later, the ice closed again and did not reopen until the return voyage.

After 32 days, 116 expedition members successfully established China’s second Antarctic research station—the Zhongshan Station—within the Antarctic Circle. Yan Qide and Liu Xiaohan said that China’s polar expeditions emerged alongside the nation’s development following the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee. It reflected the country’s scientific level and comprehensive national strength. Over 35 years, from nothing to something, from small to large, China’s Antarctic endeavors have now entered the world’s forefront. Chinese scientists’ publications in international journals rank second only to the United States.

In April 2017, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the former State Oceanic Administration honored China’s polar research advanced collectives and individuals, awarding Guo Kun and 59 others the title of “Advanced Individuals in China’s Polar Research.” That same month, 82-year-old Guo Kun appeared in the CCTV program The Reader in a wheelchair. After years of working in extreme cold, he suffered from chronic injuries and could no longer walk. He said, “This concerns national honor and dignity. I will give my all, even at the cost of my life, to accomplish this mission.”