On January 9, 1983, China achieved a historic milestone: the successful reproduction of the grand bronze chime bells unearthed from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, a vassal ruler during the early Warring States period.

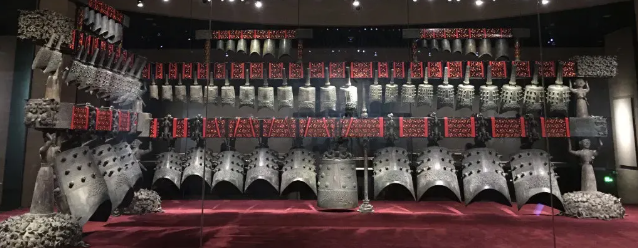

These extraordinary instruments, known as the Zenghou Yi Bianzhong, date back more than 2,400 years. The full set consists of 65 bronze bells of varying sizes, with a total weight of over 2,500 kilograms. They were originally arranged on an elaborate wooden frame, forming a court orchestra capable of performing complex ritual and ceremonial music. The reproduction of such a massive and intricate instrument was not only a cultural project but also a technological challenge, requiring the integration of acoustics, materials science, precision casting, archaeology, and engineering.

The technological breakthroughs of the reproduction project can be summarized across several critical areas:

The Zenghou Yi bells embody one of the most astonishing achievements in the history of world music: each bell can produce two distinct pitches. When struck at the central “drum” section or the side “drum” section, the bell generates two stable and independent tones.

This principle, sometimes referred to as the “dual-tone phenomenon,” reflects an advanced understanding of vibration modes and resonance by ancient Chinese artisans. For modern scientists, reproducing this acoustic principle meant decoding the physical “password” of sound that had remained hidden for more than two millennia. The success demonstrated not only fidelity to the original but also the ability of contemporary acoustics to verify and explain ancient craft knowledge.

Scientific analysis revealed that the bells were cast from a copper–tin–lead ternary alloy:Copper: 75%–85%Tin: 12%–18%Lead: 1%–5%

To uncover this composition, researchers used advanced methods such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to study fragments of the original bells and copper slag. With this data, metallurgists were able to reproduce the alloy using vacuum smelting and inert gas protection, ensuring purity and reducing oxidation.

This step was crucial, because the specific alloy composition determined not only the durability of the bells but also their tonal quality. Ancient craftsmen, without access to modern tools, had relied on generational experience to fine-tune these ratios. The 1983 project, by reverse-engineering this formula, effectively bridged the gap between empirical tradition and modern science.

The bells were reproduced using the piece-mold casting method , an ancient Chinese technique that allowed complex shapes and fine inscriptions to be cast with remarkable accuracy.

In reproducing the bells, scientists had to balance “process restoration” with “precision control.” The goal was to stay true to the techniques of antiquity while minimizing deformation in the castings through modern quality control. This required a delicate equilibrium: respecting the craft logic of the past while applying the rigorous standards of modern industrial science.

The bells are not only musical instruments but also sophisticated mechanical systems. To ensure they could be played like the originals, researchers conducted mechanical simulations, vibration analysis, and structural optimization. Every detail — from the suspension of the bells on their wooden frame to the alignment of the striking mallets — had to be carefully calibrated.

This step symbolized the fusion of archaeology and technology: the bells were reconstructed not as static relics but as living, functional instruments capable of producing the same resonant sound that once echoed through the courts of ancient Zeng.

At the heart of this project was the question: should we merely restore, or should we also surpass?

The reproduction of the Zenghou Yi bells was not simply an exercise in duplication. It was an attempt to decode the “black box logic” of ancient craftsmanship. Modern science had to simulate, measure, and verify what ancient artisans had achieved through empirical skill.

This process required both humility and innovation. On one hand, researchers needed to faithfully reproduce the intentions of ancient craftsmen. On the other, they had to translate those intentions into a modern scientific language, ensuring that the reproduction was not just a copy, but also a demonstration of understanding.

The success of the reproduction project carried profound implications:For archaeology, it offered a unique opportunity to study an ancient instrument in its functional state rather than as a static artifact. Scholars could now analyze the tonal behavior of the bells under performance conditions.For materials science, it provided empirical evidence of the sophistication of ancient metallurgy, validating that ancient Chinese bronze workers had mastered alloy ratios that remain relevant today.For cultural history, it reaffirmed the continuity of Chinese civilization. The bells are not only musical relics but also symbols of power, ritual, and knowledge from a period of intense cultural transformation.

In many ways, the reproduction echoed the original purpose of the bells: to resonate both literally and metaphorically. Just as the bells once embodied the authority and cultural refinement of a Warring States ruler, their reproduction demonstrated the resilience and creativity of modern China.

The 1983 reproduction of the Zenghou Yi chime bells was a landmark achievement at the intersection of science, culture, and history. It was about more than metal and sound; it was about re-establishing a dialogue with the past.

Through the lens of acoustics, metallurgy, precision casting, and engineering design, modern researchers brought back to life an artifact that had been silent for millennia. In doing so, they proved that ancient wisdom can be decoded, preserved, and even surpassed through the tools of modern science.

Each strike of the replicated bells is not just a musical note — it is a resonance across centuries, a voice from 2,400 years ago speaking once again in the present. It tells us that tradition and technology are not opposites but partners, each giving the other new life.

The Zenghou Yi Bianzhong thus remains more than an archaeological treasure; it is a living testament to the timeless pursuit of harmony between history, science, and human ingenuity.