Yaodong — the cave dwellings born from the loess soil — represent one of the world’s oldest and most distinctive forms of vernacular architecture. Unique to China, these earthen homes embody the “roots” of the nation’s architectural civilization and stand as living witnesses to the origin of China’s “dwelling culture.”

Scattered across the cradle of Chinese civilization — the vast Loess Plateau — yaodongs have evolved over millions of years. They are not merely shelters carved into earth; they are the crystallization of ancient Chinese philosophy and environmental wisdom. Within their curved arches and warm walls lie the essence of tian ren he yi — the traditional belief in the unity of man and nature. These dwellings integrate ancient feng shui concepts, local customs, and the labor and intelligence of generations of working people. Over time, they have formed an architectural landscape rich in cultural meaning — a humanistic expression deeply rooted in the spirit of the Chinese nation, and now recognized as a precious intangible heritage of humankind.

When one speaks of homes that stay warm in winter and cool in summer, the yaodongs of the Loess Plateau immediately come to mind. The plateau’s rugged terrain is characterized by gullies, ridges, and cliffs, making it both challenging and inspiring for human habitation. Sparse vegetation limited the availability of timber for building or heating, yet the people of the region found wisdom in their soil. The loess earth here is thick, compact, and highly cohesive, with excellent insulation and load-bearing qualities. So, instead of building on the land, people chose to build into it — carving out their homes directly from the yellow earth.

Because the local climate is dry and rainfall scarce, the loess soil — slightly sticky and firm — rarely collapses. Combined with the earth’s natural insulation and the yaodong’s enclosed design, these cave homes offered exceptional comfort: warm in winter, cool in summer. This was more than adaptation — it was architectural genius born from necessity. The land provided the material; the people provided the wisdom. Together, they built a way of life perfectly attuned to their environment.

According to the old Gazetteer of Huan County, the ancestors of the region “made pottery-bellied and earthen cave dwellings for their homes,” referring precisely to the traditional ground-pit and cliff yaodongs that have been passed down for countless generations. To this day, yaodongs remain the preferred choice of many local families — not merely because they are economical to build, but because they embody a harmony between cost, comfort, and culture. As an old folk poem goes:

“Traveler from afar, laugh not at our humble caves —

Though not celestial abodes, they are warm in winter and cool in summer.”

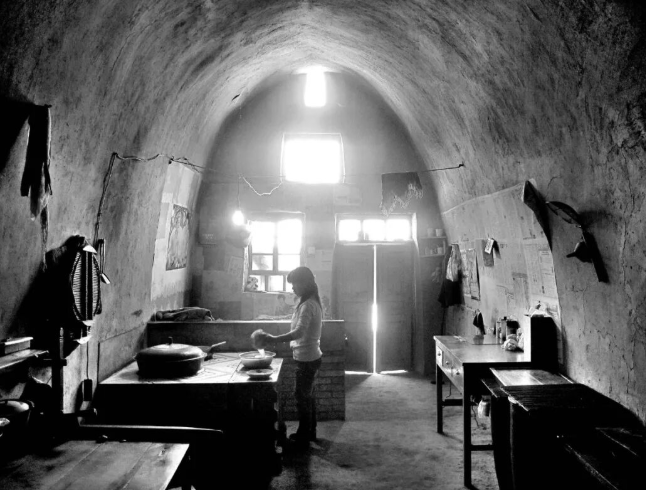

Depending on the soil type and cliff size, yaodongs vary greatly in scale. The smaller ones may have an interior space of just a dozen square meters, while the largest can stretch tens of meters wide and nearly a hundred meters deep — grand enough to resemble a spacious hall. Some even feature yao within yao — small inner chambers known locally as “turning caves,” carved into the main wall for storing vegetables, grains, or valuables.

Inside, most yaodongs are furnished with kang — traditional earthen heated beds used for rest and sleep. During winter, residents burn crop stalks, firewood, or dried livestock dung beneath the kang to warm the entire space, filling it with gentle heat and the comforting scent of earth. In summer, no matter how fierce the sun outside, the interior remains cool and calm, like a natural refuge from the heat.

Many yaodongs adopt an arched, barrel-vault design that is both beautiful and practical. The shape distributes structural pressure evenly, greatly reducing the risk of collapse, while also allowing sunlight to penetrate deeply into the room. To shield against wind and sand, a second doorway is often added outside the main entrance. Eaves made of stone slabs or bricks, topped with tiles, protect against rain erosion.

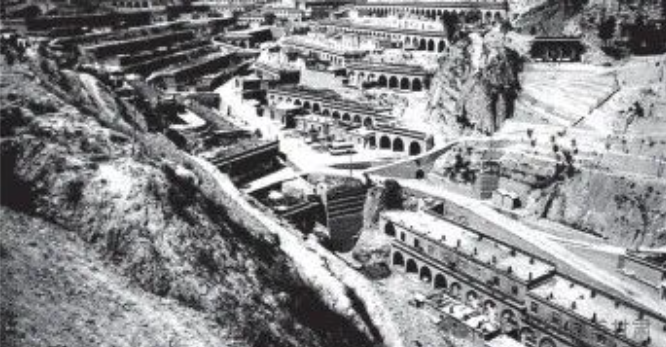

Today, yaodongs can still be found across several provinces — Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, and parts of Inner Mongolia — in forms ranging from simple earthen caves to more elaborate brick or stone versions. Depending on the landscape, they may take several forms: independent yaodongs covered by soil, semi-open slope yaodongs built into hillsides, and sunken courtyard yaodongs dug directly underground.

The sunken courtyard type — known locally as di keng yuan, tian jing yuan, or dong zi yuan — is common in southern Shanxi, western Henan, and northern Shaanxi. These courtyards resemble open-air underground dwellings, with caves excavated beneath a flat layer of earth at least three meters thick. Such sites must be dry and rarely affected by rainfall. Around the edges of the courtyards, low walls of adobe or brick are built to prevent people from falling in and to block runoff water. An inclined tunnel connects the courtyard to the surface, while a seepage well ensures proper drainage.

Besides their excellent thermal stability, sunken yaodongs save valuable surface space. The land above them is typically used for drying grains but not for planting, to preserve the stability of the loess structure. Villages composed entirely of such subterranean homes form an extraordinary landscape — where “you can hear voices but see no houses.”

No matter the type, every yaodong represents the same principle: living in harmony with the earth. These dwellings are not merely architecture; they are a dialogue between humankind and nature. Built from the soil, shaped by hand, and sustained by wisdom, yaodongs record the rhythms of survival and the persistence of culture. They are more than homes — they are the memory of a civilization carved into the land itself, a living testament to humanity’s capacity to adapt, create, and endure.