On September 28, 1958, Xinhua News Agency released a major announcement to the world:

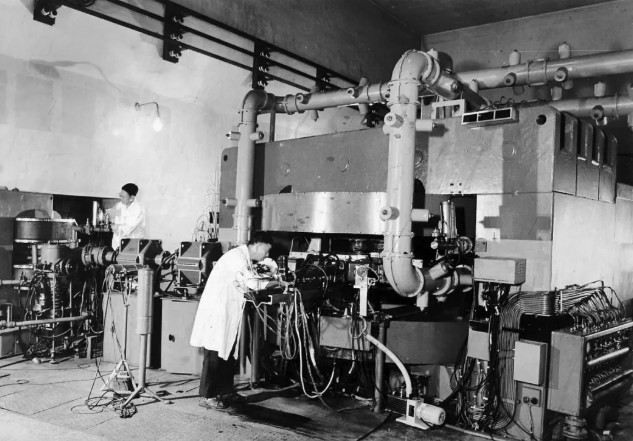

“Constructed in the outskirts of Beijing, China’s first experimental atomic reactor and cyclotron have been officially transferred to production on the eve of the ninth anniversary of National Day. The first batch of domestically produced radioactive isotopes has already come from this reactor. The neutrons and two types of radiation emitted from the channels inside the reactor core, as well as the particles accelerated to 34,000 kilometers per second by the cyclotron, are now being used in nuclear physics research. This marks a decisive stage in China’s development of nuclear science and the peaceful use of atomic energy.”

This announcement came one day after a historic event.

On September 27, 1958, the Institute of Atomic Energy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences—located in Tuoli, Fangshan County, Beijing—revealed itself to the world for the first time. Today the facility is known as the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE), one of the foundational institutions of China’s nuclear science.

At dawn, traffic control was imposed at the entrance of Tuoli village.

Cars—rare in the countryside at the time—arrived one after another.

The normally quiet compound suddenly became vibrant.

Director Qian Sanqiang, widely regarded as the father of China’s nuclear science, busily greeted arriving guests. Everyone wore broad smiles. The joyful laughter of Vice Premier Chen Yi when he met Qian Sanqiang was especially hearty, echoing across the courtyard.

At 10:00 a.m., the transfer-to-production ceremony for the “one reactor and one accelerator” began. Nearly a thousand distinguished guests attended the event.Chen Yi, Vice Premier of the State Council, cut the ribbon.Nie Rongzhen, Vice Premier and key leader of China’s defense science, signed the acceptance papers.Guo Moruo, President of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, delivered a keynote speech.Zhang Jingfu, Vice President of CAS, presided over the ceremony.The Soviet delegation, led by Yefremov, attended and addressed the gathering.

It was an unprecedented celebration.

Chinese and foreign guests, along with nearly two thousand staff members, gathered in a festive atmosphere to witness the birth of China’s nuclear era.

That evening, Qian Sanqiang personally invited his longtime friend—the legendary Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang—to perform for the staff and their families in the institute’s residential square.

The entire plaza blazed with lights. Crowds surged.

Besides institute employees, villagers from the surrounding areas were led by militia to watch the performance.

For many, it was the only time in their lives they ever saw Mei Lanfang perform in person.

Rewind the clock three months.

Physicists and engineers at the institute could never forget 4:40 p.m. on June 13, 1958—a moment engraved in the history of China’s science and technology.

At that exact time, China’s first heavy-water reactor achieved criticality, triggering a sustained chain reaction.

Power levels were gradually increased. By the time of national inspection, the reactor had already produced 33 types of radioactive isotopes, soon applied in:agriculture、medicine、machinery、new materials、petroleum exploration

What delighted Qian Sanqiang most was not the technical success itself, but the spirit behind it.

These isotopes were produced under extremely harsh and rudimentary conditions, reminiscent of Marie and Pierre Curie purifying radium in a drafty shed.

Chinese scientists, refusing to wait for ideal conditions, worked with makeshift tools in crude wooden shacks—but they succeeded.

Qian Sanqiang called this “the spirit of dedication.”

He later said:“Scientific work requires a willingness to sacrifice—and sometimes even the courage to risk one’s life. Bruno was burned at the stake for defending truth; Gao Shiqi became permanently disabled researching bacteria; early pioneers of nuclear science suffered radiation damage. Many workers in China’s nuclear industry have long toiled in extremely difficult environments, remaining anonymous heroes. This spirit of sacrifice deserves our admiration and respect.”

The other key piece of equipment—the cyclotron—entered tuning in early March.

By June, particle beams were successfully extracted from the vacuum chamber, enabling formal scientific research.

On July 1, the People’s Daily ran a front-page headline with photographs of the reactor and the accelerator.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Physics, directed by Qian Sanqiang, was renamed the Institute of Atomic Energy, placed under dual leadership of the Second Ministry of Machine Building and CAS, with the ministry holding primary oversight.

People’s Daily praised the milestone:

“The completion of the reactor and the accelerator signifies that China has entered the atomic age.”

From this point on, China’s development of nuclear science embarked on a new journey, one that would deeply influence the nation’s technological, industrial, and strategic future.

The other key piece of equipment—the cyclotron—entered tuning in early March.

By June, particle beams were successfully extracted from the vacuum chamber, enabling formal scientific research.

On July 1, the People’s Daily ran a front-page headline with photographs of the reactor and the accelerator.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Physics, directed by Qian Sanqiang, was renamed the Institute of Atomic Energy, placed under dual leadership of the Second Ministry of Machine Building and CAS, with the ministry holding primary oversight.

People’s Daily praised the milestone:

“The completion of the reactor and the accelerator signifies that China has entered the atomic age.”

From this point on, China’s development of nuclear science embarked on a new journey, one that would deeply influence the nation’s technological, industrial, and strategic future.