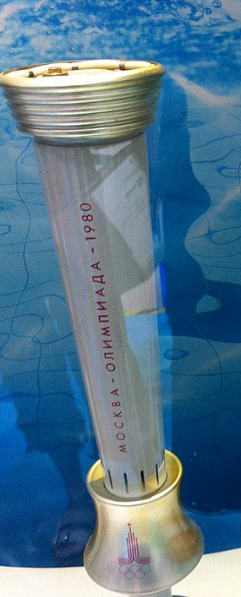

Dubbed “the most absurd Olympic Games in history,” the 1980 Moscow Olympics marked the first and only time the Soviet Union ever hosted the Olympic Games. Just eleven years after the event concluded, the Soviet Union officially dissolved.

The 22nd Summer Olympic Games were held in Moscow, USSR, from July 19 to August 3, 1980. The main venue for the Games was the Central Lenin Stadium in Moscow.

It is worth noting that only two cities bid to host this edition of the Olympics: Moscow and Los Angeles. While Los Angeles did not win the right to host the 1980 Games, it eventually hosted the 1984 Summer Olympics. During that era of heightened political tension, the United States and the Soviet Union competed in every possible arena. Since the USSR hosted the Olympics in 1980, it was almost inevitable that the next Games would take place in the United States. In the final vote to decide the host city for the 1980 Olympics, Moscow defeated Los Angeles by a vote of 39 to 20.

If not for a pivotal event in 1979 that altered the fate of the Soviet Union, the 1980 Moscow Olympics might never have faced such widespread international boycott. So, what exactly happened?

In late December 1979, the Soviet Union launched an unprovoked invasion of Afghanistan—an event later known as the “Soviet–Afghan War.” Despite the vast disparity in military strength, the war dragged on for nine long years due to complex geopolitical and environmental factors. This invasion is widely regarded as one of the Soviet Union’s greatest foreign policy blunders and a major reason for its eventual decline and collapse. But today, we’re not discussing war—we’re focusing on the Olympic Games.

On March 21, 1980, in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, U.S. President Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would boycott the Moscow Olympics. This call was echoed by over 50 countries around the world, including China, Japan, Canada, and West Germany. Some countries chose not to send official delegations, while others marched under the Olympic flag instead of their national banners during the opening ceremony and medal ceremonies.

Among the more than 50 boycotting nations was China. In 1979, China had regained its legitimate seat in the International Olympic Committee through the “Nagoya Resolution,” and the 1980 Olympics could have marked China’s return to the global Olympic stage. However, China ultimately chose to stand on the side of justice, joining over 80 countries and regions in boycotting the Moscow Games.

These 80 participating entities fell into five categories:

-

64 countries and regions, including China, the United States, and West Germany, announced a complete boycott and did not send any athletes.

-

Seven countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, San Marino, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, sent athletes but did not participate in the opening ceremony.

-

Two countries, the United Kingdom and Ireland, allowed athletes to enter the opening ceremony as individuals without official national delegation.

-

Four countries, Australia, Denmark, Andorra, and Puerto Rico (a U.S. territory), competed under the Olympic flag in both the opening ceremony and the competition.

-

Three countries, Spain, Portugal, and New Zealand, used their National Olympic Committee flags instead of national flags.

There was also a significant aftereffect: in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, the Soviet Union led a counter-boycott. Citing security concerns, the USSR withdrew from the Games, along with 15 allied socialist countries. In total, 18 nations joined the boycott. Notably, Iran and Albania were the only two countries to boycott both the 1980 and 1984 Olympics.

Ironically, the 1984 Olympics marked China’s first official return to the Games since regaining its legitimate Olympic status. That year, Chinese athletes delivered a strong and memorable performance on the global stage.

Meanwhile, the issue of doping at the Olympics has always been highly sensitive and deeply damaging. Since 1968, nearly every Olympic Games has witnessed doping-related scandals, with most revoked medals tied to the use of banned substances.

However, what makes the 1980 Moscow Olympics particularly absurd is that, despite the fact that since 1968 the sports world had widely acknowledged the necessity of drug testing to ensure fair competition, the Moscow Games stood out as a bizarre exception. Under the overwhelming control of the Soviet Union, the 1980 Olympics became the only Olympic Games since 1968 that conducted no drug testing whatsoever.

As a result, the athletic achievements of the 1980 Games are, by nature, difficult to verify as legitimate. The lack of any anti-doping measures cast a long shadow over the credibility of the results, leaving this edition of the Games permanently stained by doubt.

This Olympic Games, in essence, was boycotted by nearly half of the countries around the world. Did the Soviet Union not realize this? Of course they did. But for those working in the field of sports, there was little they could do to reverse the fact that a controversial invasion war had already taken place.

And so, during the closing ceremony of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, a particularly poignant moment occurred — the famous scene known as “Misha’s Tears.”

The bear is a beloved and widely recognized animal in Russia, often seen as a national symbol and featured in countless Russian fairy tales. For this reason, the Soviet Union designed Misha the Bear as the official mascot of the Games — a brown bear wearing a belt decorated with the Olympic rings.

The emotional impact of Misha the Bear’s tears during the closing ceremony, paired with the theme song “Farewell, Moscow”, resonated deeply with the audience. The performance was a subtle but powerful expression of regret from the sporting community — a lament for the global boycott that overshadowed the Games.

The roots of this sorrow trace back to the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which drew widespread international condemnation and led to the mass boycott.

To this day, Misha’s tears are remembered not just as a moment of Olympic emotion, but as a symbol of a lost opportunity. The song “Farewell, Moscow” echoed through the stadium as the bear floated away, waving goodbye — a goodbye that turned out to be final.

The Soviet Union never had the chance to host another Summer Olympics. Just eleven years later, the USSR collapsed, making Misha’s farewell an eternal one.

In the end, a total of 204 gold medals were awarded during the event, and the host nation, the Soviet Union, claimed an astounding 80 gold medals, ranking first. In addition, the Soviet team also earned 69 silver medals and 46 bronze medals — a dominance that could only be described as invincible.

Coming in second was East Germany, also known as the German Democratic Republic — a close Soviet ally and the birthplace of many early performance-enhancing drug programs — which secured 47 gold medals. Bulgaria and Cuba followed with 8 gold medals each, placing third and fourth respectively. Interestingly, Italy, which had its athletes compete under the Olympic flag instead of its national flag, also won 8 gold medals, but due to having fewer silver and bronze medals, it ranked fifth.

It must be said that this was an Olympic Games difficult to interpret through a normal lens. The event concluded with the Soviet Union and East Germany together sweeping over 62% of the total gold medals, turning the competition into something of a one-sided performance.

But behind this overwhelming show of strength lay a deeper geopolitical upheaval. While the Soviet Union may have appeared to achieve total victory on the surface, it would, just eleven years later, fade from the world stage with the collapse of the USSR.

This entire episode far surpassed the scope of competitive sports. It was not merely an athletic spectacle — it was a historical turning point, a symbolic performance staged in the twilight of an empire.