I was born after the 1980s, so I have no direct memories of China’s family planning policy. It was something my parents and older relatives often talked about when I was younger, but as the years passed, they rarely brought it up again.

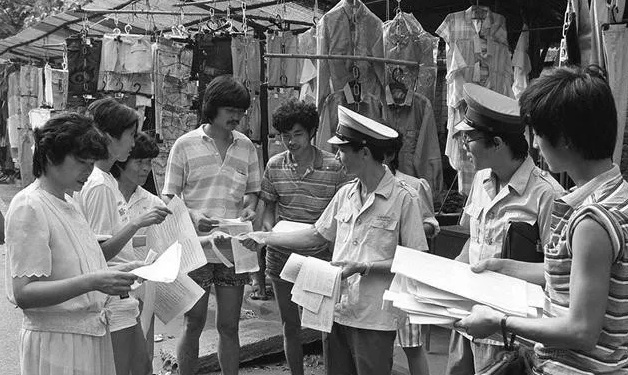

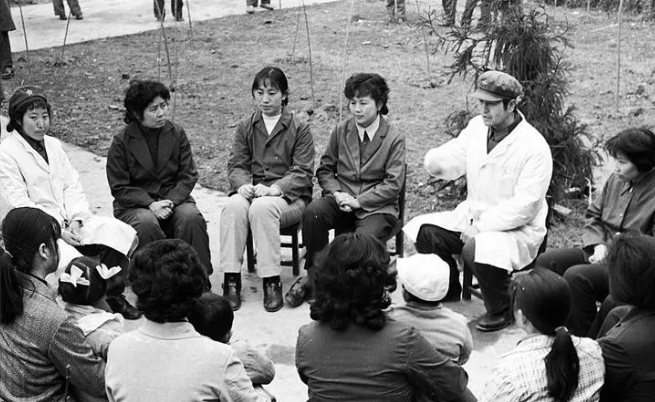

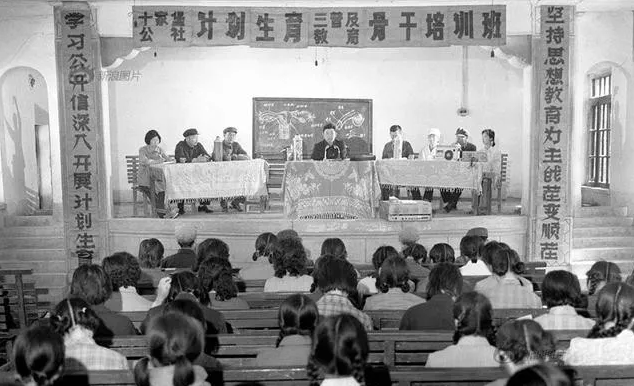

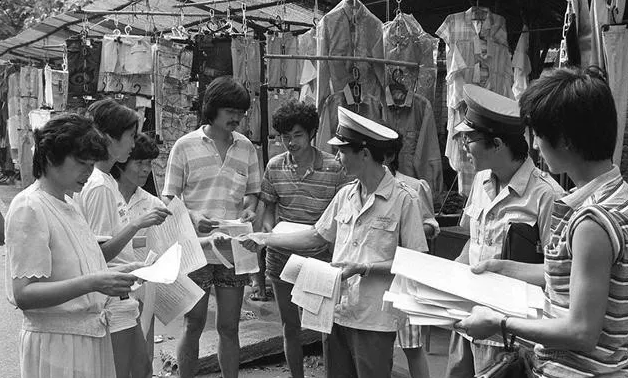

Back then, family planning was not just a policy—it was one of the most important national strategies, enforced with particular intensity in the countryside. Propaganda slogans were everywhere: painted on walls, hung on utility poles, printed on banners and posters, or shouted out during village meetings. Reports and lectures were given in public halls. Some of the most familiar phrases included:“It is good to have only one child.”“From every corner of the land, family planning is a national policy, applied equally to all.”“Having a boy or a girl is the same.”

As my elders recalled, whenever there was word that family planning officials were coming to check, the entire village would be thrown into an atmosphere of panic. The moment someone shouted, “The people from above are here to check family planning!” it was as if a siren had gone off.

People would rush around frantically, dropping everything, with one priority only: to hide. Families suspected of having more children than allowed would mobilize at once. If a woman was pregnant with a second child and intended to keep the baby, she would be hurried away to a relative’s home.

There, she would live quietly and secretly for months, waiting until the baby was safely born and the inspections had eased before daring to return. Some of my aunts and older female relatives have mentioned this more than once—saying things like, “She had to come back quickly to give birth, or else, where else could she go?”

Others recalled how little choice there was: as long as someone was willing to shelter a pregnant woman, she would stay there—sometimes for months. She would spend that time in hiding, going through pregnancy, childbirth, and even the confinement period after birth before returning home.

As a child, whenever I heard these stories, I treated them like legends. I would listen nervously, unable to imagine such a tense atmosphere. In my mind, it always felt like the scenes from Tunnel Warfare—villagers hiding from danger, living in fear of discovery.

For those unlucky enough to be caught before they could hide, the consequences were severe. According to what my elders told me, sometimes pregnant women were taken by tractor to the township health clinic, where they were forced to undergo procedures in line with the family planning policy.

In my own family, there were many such stories. Several of my relatives were fined for having a second child. In those years, when economic conditions were already difficult, a fine was a crushing financial burden. Families often had to save every penny, live frugally, or even sell their most valuable possessions to pay the penalty.

And yet, despite the risks and hardships, some families still chose to have more children. Perhaps it was due to the deeply rooted traditional belief in “more children, more blessings.” Or perhaps it was simply the irresistible pull of a parent’s love—the refusal to let go of the chance to bring a new life into the world.

In those days, family planning slogans were everywhere: painted in large characters on the sides of village homes, printed on posters pasted to utility poles, even hand-painted in bold strokes on public walls.

Village cadres would go door-to-door, tirelessly explaining the policy, pleading with families to comply. Enforcement was strict, and the process was often filled with bitterness and helplessness. Yet, looking back with the perspective of history, one cannot deny that the family planning policy did play a role in curbing population growth and easing the strain on resources at that time.

Today, the world has changed dramatically. The policy itself has shifted and relaxed over time. The fear, anxiety, and helplessness that once weighed so heavily on families have slowly receded into the past.

And yet, for those who lived through it, those memories remain like etched scars of history—a reminder of the sacrifices, the secrecy, the fear, and the resilience of ordinary people.

For me, family planning is not something to judge harshly or praise lightly. Every era has its background and its necessities. What I want to emphasize is the love and sacrifice of parents. No matter the circumstances, they always endured hardships to protect their children and provide them with a future. Truly, as the old saying goes: “The heart of a parent is the most selfless in the world.”

The years were heavy, but they were carried away by the tides of history. I only hope that in whatever era we live—past, present, or future—every family can live with happiness, peace, and health.

Family planning was once a national story written on the walls of villages, painted in bright red characters, remembered in the whispers of women hiding in relatives’ homes. Now, it has become part of collective memory—a mixture of fear, resilience, and unspoken love.

And as we look back, we do not merely revisit an old policy; we see the shadows of our parents and grandparents—their sacrifices, their resilience, their silent devotion.