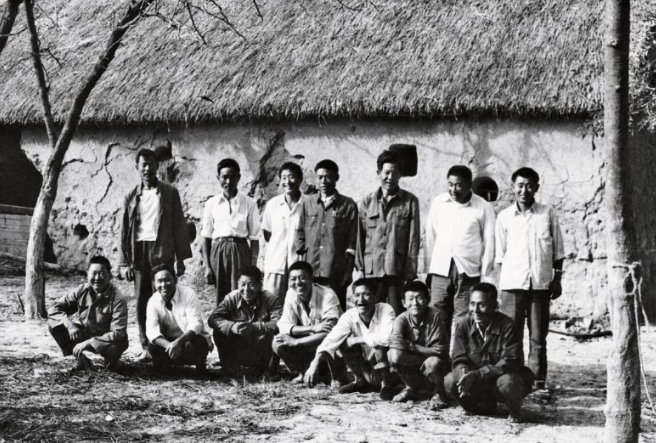

In November 1978, 18 villagers from Xiaogang Village, despite not receiving any formal policy endorsement, created an astonishing agricultural turnaround within just one year. By 1979, Xiaogang Village experienced a bumper harvest! The total grain yield skyrocketed from the previous 30,000 jin to over 130,000 jin, which was more than the combined total yield of the previous five years. Oilseed production increased to 35,000 jin, surpassing the total yield of the past two decades. This “big contract” model helped the villagers not only solve their basic food needs but also tore down the long-standing barriers, creating a miraculous reversal!

In the Shan Nan Commune of Feixi County, Anhui Province, in a drought-prone and barren land, the Xiaojingzhuang team was able to sow 70 acres of wheat and 32 acres of oilseed in just one week. The next year, their total grain production increased from 30,000 kilograms to 45,000 kilograms. This small-scale “household responsibility system” blossomed in the sweltering heat and harsh cold, achieving remarkable results that inspired widespread hope and success.

Since the groundbreaking U.S. visit by Nixon in 1972, major Western leaders from countries like the U.S., the UK, Japan, and others had visited China, but China had not reciprocated these high-level visits for various reasons. Thus, after the Cultural Revolution, China’s leadership became more conscious of the need to conduct return visits. In 1978, 12 vice premiers and national leaders, including the Vice Chairmen of the National People’s Congress, made 20 visits to 51 countries. That year also marked a peak in Deng Xiaoping’s diplomatic engagements, as he made visits to Myanmar and Nepal in early 1978, to North Korea in September, to Japan in late October, and to Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore in November.

The personal observations from these visits, along with reports from other study groups, strengthened his sense of urgency and helped him refine his reform agenda. In 1977, the issue of preparing a modernization long-term plan was put on the agenda. Foreign imports were seen as a critical way to achieve this and secure necessary resources. The most significant mission of 1978 was the tour of five Western European countries led by Vice Premier Gu Mu. The delegation, which included Minister of Water Resources Qian Zhengying, Deputy Minister of Agriculture Zhang Gensheng, Vice Governor of Guangdong Wang Quanguo, and other senior officials, visited France, West Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Denmark. During their visit, they observed 25 cities and over 80 institutions.

Upon their return, the delegation submitted a report titled “Report on the Situation of Visiting Five European Countries”, and the meeting described at the beginning of this article followed. Before the delegation left, Deng Xiaoping had a private discussion with Gu Mu and then asked for another meeting to inquire in detail about the visit. During this conversation, Deng emphasized three points: first, the necessity of introducing foreign technology, second, the need to borrow foreign capital for construction, and third, the urgency of seizing time to develop.

Hua Guofeng, in particular, was both enthusiastic and highly supportive of the information brought back from this tour. According to Hu Yaobang’s report to the Central Party School, on July 6, Hua Guofeng held a long discussion with him, lasting from 3:00 p.m. until after 1:00 a.m. He repeatedly asked, “Yaobang, do you think we can take even larger steps to make our country rich and powerful? Use my words: ‘flourishing and prosperous.'” Hua proposed continued international visits, saying, “Not only ministers, vice chairmen, and vice premiers, but even some factory directors should go abroad. I myself will also go abroad later this year.” He also emphasized the need for senior officials to learn the economic laws of the socialist period.

From introducing advanced foreign technologies and equipment to introducing foreign capital, this transition in policy was one of the most significant breakthroughs around 1978. According to data from the International Monetary Fund, by the end of 1978, China’s foreign exchange reserves stood at a mere $1.557 billion. How could China fund its development? Two solutions were considered: one was to raise domestic savings rates, and the other was to borrow foreign funds. Domestic savings had already reached their peak, with an accumulation rate exceeding 30%. This left the only viable option: to borrow money from abroad for development. This shift in thinking—borrowing funds for construction—was key to the restructuring of China’s economy.

The discussions about reforming China’s urban economic system initially focused on expanding corporate autonomy. In late October to early December 1978, the National Economic Commission sent another delegation to Japan to conduct studies. The delegation members, including Yuan Baohua, Deng Lijun, Ma Hong, Sun Shangqing, and Wu Jiajun, all asserted that China needed to develop a commodity economy. They also emphasized that this development could only be achieved if enterprises were allowed to produce according to market demand. In their report submitted to the State Council, the delegation proposed the issue of developing a commodity economy and corporate reforms in China. Li Xiannian, one of the leaders supporting this idea, stated, “To improve the economy, we must first improve the enterprises. We must expand corporate autonomy.”

In August 1978, the First Secretary of the Sichuan Provincial Party Committee, during his visit to Yugoslavia with Hua Guofeng, suggested that Sichuan should be allowed to take the lead in reform. His proposal included granting farmers, particularly those in the surrounding mountainous areas, the autonomy to decide their own production and allowing state-owned enterprises to reform their distribution systems to stimulate economic vitality. Hua Guofeng agreed to let Sichuan lead the reforms. The National Economic Commission supported pilot projects in various areas, and after research, the “Ten Measures for Expanding Rights” were formulated. However, the Ministry of Finance expressed concern that expanding rights would impact national fiscal revenues, leading to disagreements with the National Economic Commission. In the July 1979 National Industrial and Commercial Meeting, a representative from Yunnan Province used data to demonstrate that expanding rights did not reduce fiscal income; instead, it increased revenue. This ultimately convinced the Ministry of Finance and led to a consensus on reform.

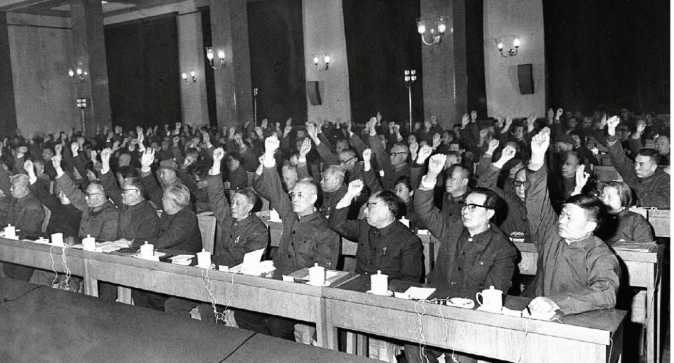

On the evening of December 18, the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee opened. As the meeting concluded, a new historical chapter for China’s reform and opening-up officially began.

This marked the dawn of a new era for China, signaling the country’s shift from rigid central planning to a more flexible and open economic system. The Third Plenary Session introduced reforms that would gradually transform the national economy, opening doors to both domestic and international markets, as well as accelerating technological and industrial modernization.

The agricultural reforms, represented by the household responsibility system, and the economic restructuring, which gave more autonomy to enterprises, were crucial turning points. These reforms would eventually set the stage for China’s rapid economic growth in the following decades. The seeds of today’s Chinese economic power were planted during this pivotal moment, leading to a China that would not only be a major global player but also a leader in technological and industrial innovation.