1984 — forty-one years have passed since that fateful year.

It was a year rich in metaphor and meaning.

Back in 1948, British writer George Orwell published Nineteen Eighty-Four, a prophetic novel that envisioned a totalitarian world where the pursuit of power had no limit — a society where the individual was crushed under the weight of control and surveillance. Orwell warned that all forms of authoritarianism, regardless of their banner, would inevitably lead to national tragedy and human suffering.

Yet when the real 1984 arrived, the world did not mirror Orwell’s dystopia. Instead, the invisible hand of the market began to rise, while the visible hand of the state started to retreat. The era of Reaganomics and Thatcherism reshaped global capitalism — their shared belief was to redefine the boundary between government and market: restrain the “visible hand,” and unleash the “invisible” one.

Across the world, 1984 became a year of economic realignment.

Some of the old industrial giants in the West were collapsing or splitting apart, while entirely new sectors — information technology, electronics, and communications — began to sprout. New heroes of enterprise were about to step onto the stage.

Apple captured this spirit perfectly in its now-legendary commercial:

“On January 24th, 1984, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

As Stefan Zweig once wrote in The Star Moments of Humanity:“Before a truly historic moment arrives — a moment that shines for all of humanity — countless years may pass meaninglessly. But when it comes, time itself seems to contract, and everything converges into that one decisive instant that alters the destiny of a person, a nation, or even mankind.”

For China, 1984 was such a defining moment.

For China, 1984 was such a defining moment.

At the start of that year, Deng Xiaoping made his first “Southern Tour,” signaling the dawn of deeper reforms. By year’s end, the Third Plenary Session of the 12th CPC Central Committee adopted the Decision on the Reform of the Economic System, clarifying the urgency of accelerating market-oriented transformation — especially in urban industries.

It emphasized granting greater autonomy to enterprises, separating government functions from enterprise operations, and invigorating the economy through competition.

From that moment onward, Chinese enterprises began to obtain the basic rights of independent market entities — the ability to allocate resources, appoint personnel, manage internally, distribute bonuses, and decide profit arrangements.

These may seem like small freedoms today, but in 1984, they were nothing short of revolutionary.

They were the golden keys that unlocked the door to the market.

1984 is now widely regarded as the birth year of modern Chinese companies.

It was a restless, fervent, and transformative year.

That year, countless people cast aside the so-called iron rice bowl — the lifelong guarantee of a government job — and plunged into the uncharted waters of entrepreneurship.

According to the China 1978–2008 Economic Review, the number of individual businesses reached 5.9 million in 1984, a staggering 126% increase from the previous year. Employment in private enterprises rose by 133.4%, and total retail sales of consumer goods, long hovering around 10%, suddenly surged to 19.4%, and 31.1% the following year.

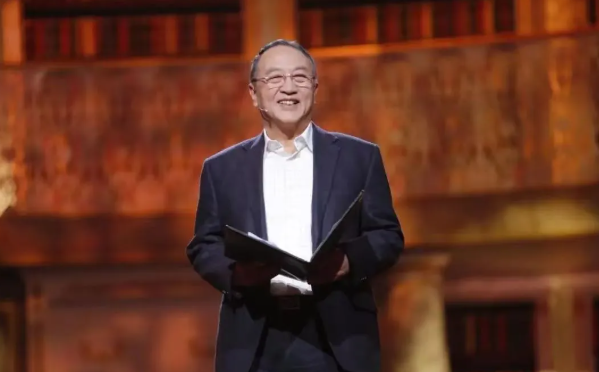

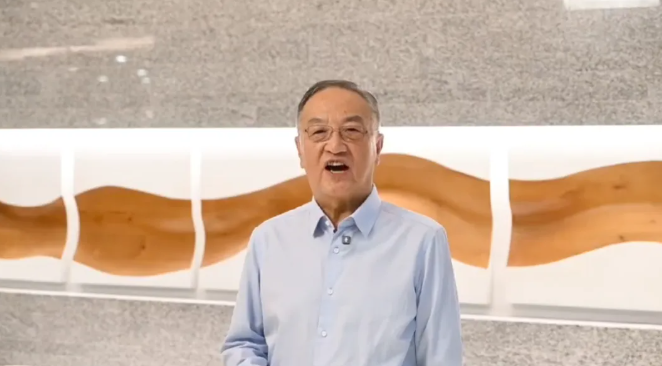

Across the nation, a wave of “unknown enterprises” emerged from the ground. Many of their founders would later become legendary figures — Liu Chuanzhi, Wang Shi, Zhang Ruimin, Li Dongsheng, Li Jingwei, Liu Yonghao, Nan Cunhui, Zheng Yuanzhong, Ma Shengli, Pan Ning, and many more.

Indeed, 1984 was a year of turbulence and passion, a year when a generation of dreamers began reshaping the economic destiny of China.

In 1984, Liu Chuanzhi was forty years old and felt like a man without achievements. He had been “promoted” from an engineer to deputy director of personnel, but the institute he worked for — the Institute of Computing Technology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences — was struggling.

Funding was dwindling fast. Desperate, the institute’s director, Zeng Maochao, sought help from superiors, only to be told:

“The money is already in the customer’s pocket. If you have the ability, go and earn it.”

At that time, other research units around Zhongguancun — such as Jinghai, Kehai, and Sitong — were already thriving with their spin-off ventures. Inspired, the Institute of Computing submitted a proposal to form its own company.

Zeng approached Liu and said quietly:

“Let’s send out a hidden team. If it fails, I’ll bring you back. But if it succeeds, at least we’ll have a way to survive.”

Liu, together with Wang Shuhe and Zhang Zuxiang, formed the founding trio. They soon gathered 11 people — a small group of discontented engineers with big dreams but few resources.

On October 17, 1984, the new company was officially founded.

There was no ribbon-cutting, no government ceremony — just a 20-square-meter room, once a guardhouse near the west gate of the institute.

“It was a gray brick room divided into two,” Liu later recalled. “Concrete floor, lime walls, no desks, no computers. A few old benches lined the wall — furniture people had thrown away.”

That humble space would later be compared to HP’s famous garage in Silicon Valley.

Despite its prestigious parent institute, Liu’s new company had no viable projects at first. He spent days bicycling through Beijing, searching for opportunities.

To keep the small team fed, he sold electronic watches and roller skates by the gate, later trying wholesaling sports shorts and refrigerators.

Once, he heard of a woman in Jiangxi selling color TVs — each could earn 1,000 yuan in resale profit. He wired the money immediately — and was scammed.

Of the 200,000 yuan seed funding, 140,000 yuan vanished overnight.

At the time, a senior professor earned less than 200 yuan a month. Liu himself earned just 105.

Their first real income came in early 1985 when the Chinese Academy of Sciences bought 500 IBM computers and outsourced the testing, maintenance, and training to Liu’s team. The deal brought in 700,000 yuan, and more importantly — a relationship.

Through this project, Liu connected with IBM’s newly formed China office, becoming one of its earliest authorized agents.

Selling IBM computers would become Lenovo’s most profitable business line for years — and two decades later, in poetic symmetry, Lenovo would acquire IBM’s PC division for $1.6 billion.

By 1984, China already had 110,000 personal computers.

An imported PC/XT — technologically inferior to the 286 — cost 20,000 yuan at the port, and 40,000 yuan in Zhongguancun.

But all these machines ran only in English, making the development of a Chinese-character system both an urgent need and a lucrative business.

Among many researchers tackling this challenge was Ni Guangnan, a brilliant engineer who devised a breakthrough solution — the “Lenovo Function.”

Ni’s system leveraged the structure of Chinese words and the frequency of homophones to drastically reduce repetition rates in two-character and three-character phrases, doubling the input speed compared to existing systems.

By early 1985, Ni had completed his “Lenovo Chinese Character System.”

Liu, eager to commercialize it, approached Ni with a simple promise:

“I guarantee that everything you’ve invented will become a product.”

For a Chinese scientist with a deep sense of national mission, that was irresistible.

The Lenovo I-Type Input Card soon became a sensation, generating 3 million yuan in sales in its first year.

Within six months, it sold over 100 units and earned 400,000 yuan in profit.

The product’s success redefined the company — and “Lenovo” became its permanent name.

Over the next four decades, Lenovo would face countless crises — market downturns, leadership transitions, global competition.

Yet today, Lenovo stands as a global technology leader, generating over 400 billion yuan in annual revenue, employing nearly 70,000 people worldwide, and holding 23% of the global PC market share — the No. 1 PC maker in the world.

But back in 1984, no one could have believed this was possible.

When Liu Chuanzhi first met with CAS Vice President Zhou Guangzhao, Zhou asked him what he envisioned for the company. Liu replied with youthful conviction:

“One day, we will become a company with 2 million yuan in annual output.”

History, as always, had far grander plans.