From 1974 to 1994, I worked for 20 years in the Cosmic Ray Research Laboratory at the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP). During this time, I had the privilege of participating in some early developments in cosmic ray research. IHEP marked the beginning and an important phase of my scientific career, with many unforgettable experiences. I participated in the automation and trigger selection transformation project at the Yunnan High Mountain Station’s large cloud chamber group, and radiation flux monitoring inside China’s first return satellite capsule.

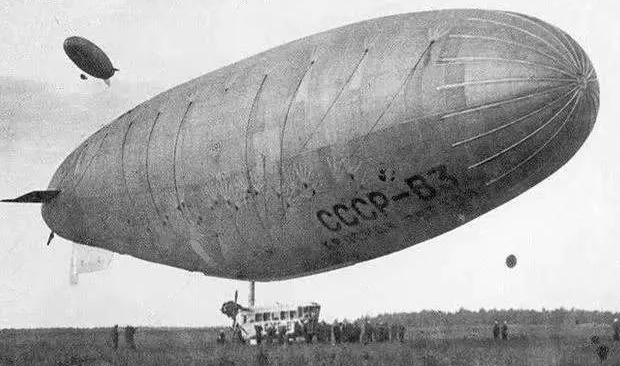

After the Cultural Revolution ended, a spring-like warmth filled the air, while the urgency to bridge the gap as the country’s gates opened was palpable in the scientific community. Faced with the growing energy of international accelerators, there were many discussions about the future development of cosmic ray research, which had long been an important tool in particle physics research. In June 1977, after much preparation, the Institute held a cosmic ray planning meeting where Li Tibei presented a report on “An Introduction to Cosmic Ray Astronomy.” The discussion was lively. The meeting decided that while continuing to advance ultra-high-energy cosmic ray research, a new astrophysics group would be formed, shifting part of the focus to high-energy astrophysics. It was essential to avoid the Earth’s atmosphere to observe cosmic high-energy electromagnetic radiation and primordial cosmic rays. At the time, satellite observations were not yet feasible, but balloons flying at the upper layers of the atmosphere became the key method for initial development. The meeting outlined a plan to “master high-altitude balloon technology within eight years and begin cosmic ray astrophysics observations, followed by the goal of satellite launches.” This meant that we would have to start from scratch, creating the necessary conditions to develop high-energy astrophysics research. Following this decision, I was appointed to lead the balloon project, and without hesitation, I accepted.

Together with my colleagues, I carried out further research and planning and wrote the proposal on “The Development of High-Altitude Scientific Balloons in China,” which we formally presented at the National Natural Science Discipline Planning Conference in September and October 1977. It was there that we learned that space agencies in the U.S., France, and Japan had already developed advanced systems for scientific balloons, including large balloons, deployment facilities, telemetry, tracking and control, capsule attitude control, and recovery systems. China was starting essentially from zero, and it was clear that we needed breakthroughs in balloon materials, design and manufacturing, and deployment technology, and we would need to mobilize forces from across the country to build a complete system.

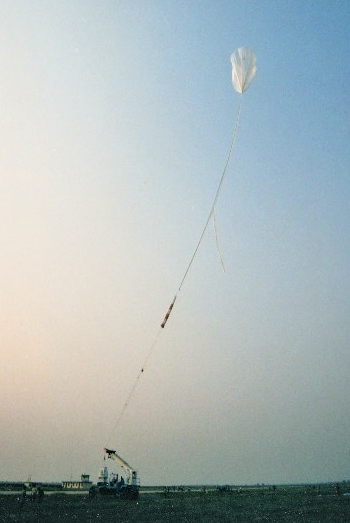

To gain the necessary experience, we began developing balloon membrane materials that same year. We tested 70, 100, and 300 cubic meter balloons at the Atmospheric Institute’s Xianghe Observatory, followed by tests with 500 and 1000 cubic meter balloons in 1978. We used weather radar and sounding instruments to test flight performance (Figure 1). At the same time, I started to make up for the lack of knowledge across different fields, reaching out to various research institutions, universities, and industries such as electronics, aerospace, chemicals, and textiles for consultations and cooperation.

In the summer of 1978, IHEP held its first high-altitude balloon meeting to discuss the organization and development of the balloon project. Mr. He Zehui and others strongly urged us to push forward the development of scientific balloons. A balloon science conference was also held that year, where Zhou Xiuji, Li Tibei, and Lü Daren presented reports on multi-disciplinary balloon observation studies. At the time, IHEP’s accelerator research was fully underway, and the Academy of Sciences was working on its “two satellites and one station” mission (astronomical satellite, remote sensing satellite, and ground station). The high-altitude balloon project was not a priority. However, in the relatively open and democratic environment, with strong support from senior scientists, the project was put on the agenda.

In September 1978, the Academy’s Secretariat approved the first phase of the Institute’s high-altitude scientific balloon project. The leadership team consisted of Vice President Ye Duzheng, with Zhao Beike, Wang Zunji, He Zehui, Zhou Xiuji, and others as members. The participating units and their responsibilities were as follows: IHEP was responsible for balloon development, deployment facilities, and recovery systems; the Atmospheric Institute for telemetry channels, tracking, and deployment fields; the Space Center for telemetry and data transmission; the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory for capsule attitude control technology; and the Guangzhou Institute of Electronics for the recovery beacon and direction-finding equipment. A technical group was formed, with Li Yi, deputy director of IHEP, as the group leader, and I served as the executive deputy group leader. The first phase of the project officially began in 1979.

I suspended my participation in the institute’s English oral training courses to fully dedicate myself to this project. Due to the intensity of the work, I was also unable to attend my beloved grandmother’s funeral, only able to send her my final thoughts in my heart.

In the summer of 1978, we began comprehensive preparations for the main balloon systems. From 1979 onwards, the project proceeded through a process of simultaneous development and testing, much like modern-day rapid iteration. To ensure the balloon could reach the stratosphere and withstand the low temperatures between -75 and -85°C at the tropopause, the balloon film required high molecular weight low-density polyethylene resin (with a melt index MI ≤ 0.3). The only domestic producer was the Jifeng Chemical Factory, where Yuan Kewei spent long hours at the factory selecting stable and qualified materials.

The balloon film had to be manufactured into wide, extremely thin (18-20 microns), uniform thickness, and low mechanical/physical property variation materials. I worked closely with the manufacturer to develop production processes, including night shifts at the factory to ensure the processes were implemented correctly. The balloon’s spherical design followed the internationally accepted “natural shape,” and we gradually improved the load factor, inflation/deflation pipe, and other design guidelines. We carefully studied the stress distribution and error control requirements of the balloon, exploring more reasonable balloon shapes and design methods, which ensured the balloon’s basic performance.

We also designed and developed all of the balloon flight control equipment, including the balloon vent valve, electromagnetic ballast valve, timing-pressure controller, and explosive separation devices. The balloon deployment needed to cope with ground wind interference, including the hazardous “sail” effect and wind direction and force changes impacting the balloon and capsule’s launch safety. The large hydrogen gas injection was risky and required technical support and experience accumulation.

The first-phase project used static deployment, with the balloon held and released in place. Equipment was designed and manufactured by IHEP’s factory, and testing began in 1979. Initial trials were conducted within IHEP’s campus, then at a larger field off-campus. In 1982, a deployment site was built 4 kilometers west of Xianghe County, covering about 25 acres. The static release system was equipped with a “windproof sealing” system (manual unlocking and air pressure switch unlocking), which successfully ensured the deployment of balloons with a total buoyancy of up to 600 kilograms.

Through years of development and collaboration, we successfully launched 50 balloons by 1984, conducting scientific observations such as primary cosmic ray composition measurements, solar infrared brightness-temperature measurements, cosmic ray nuclear interaction studies, atmospheric ionization detection, gamma ray background measurements, and Crab Nebula pulsar observations. Our high-altitude recovery parachutes also saw significant improvements, addressing challenges with low-density atmosphere and parachute deployment failures at high altitudes. By 1984, we achieved successful deployments of balloons with up to 50,000 cubic meters of volume, carrying up to 450 kg of scientific equipment, reaching flight altitudes of 35 km.

One of the most significant achievements was the observation of the Crab Nebula pulsar PSR-0531 in 1984, which marked China’s first detection of a pulsar’s hard X-ray pulse period. This breakthrough won the CAS Natural Science Second Prize and showcased China’s ability to engage in scientific exploration using balloon-based systems.