The reason the land market at that time allowed market forces to intervene was, in fact, a “temporary” measure. It emerged under circumstances where state power was insufficient, the country was grappling with both internal and external pressures, yet there was an urgent desire for rapid development. This was essentially an “additional subsidy” granted to the market and grassroots organizations. The logic was similar to the well-known policy: “Let some people get rich first.”

In the 1980s, Shenzhen was established as a Special Economic Zone. Everything was in ruins, and massive funding was urgently needed for reconstruction. Following the central government’s directive—“Be self-reliant and break new ground”—Shenzhen officials conceived the idea of raising funds by selling land use rights.

Around the same time, Shanghai was facing the decline of its old industrial base, pressure to submit tax revenues to the central government, and crumbling infrastructure—“800,000 coal stoves, 800,000 toilets, and tens of millions of square meters of dilapidated housing.” The city’s fiscal income could barely support its day-to-day operations, let alone fund the development of Pudong.

In such a context, Shanghai officials also began studying Hong Kong’s land lease model as a possible solution to financial hardship.On Buxin Road in Luohu, Shenzhen, beside Dongxiao Garden, a stone wall engraved with the words “The First Hammer of China’s Land Auction” catches the eyes of passersby. This marks the site of the first piece of land in China whose land-use rights were auctioned, and now, it is a completed residential community.

Let’s rewind time to 4 PM on December 1, 1987. The Shenzhen Civic Center, capable of accommodating over 1,000 people, was packed. Even the aisles were crowded. The first public auction of state-owned land-use rights in New China was about to begin.

Representatives from enterprises, banks, and government agencies gathered. Over 60 journalists from domestic and international media had already set up their equipment, ready to document history.

This auction drew nationwide attention because, at the time, land auctions were virtually unheard of, and there was no legal precedent for such an act.The 1982 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, Article 10, Clause 4, clearly stated:

“No organization or individual may seize, buy, sell, lease, or otherwise illegally transfer land.”

However, on May 21, 1987, the Shenzhen Municipal Party Committee Standing Committee discussed the “Reform Plan for Land Management in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone.” It decided to adopt public auctions, bidding, and negotiated transfers to sell land-use rights and allow land circulation, transfer, sale, and mortgage.

By November of that year, the State Council approved pilot reforms in Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and other regions regarding land-use systems. And on December 1, the Shenzhen government held China’s first land-use auction.

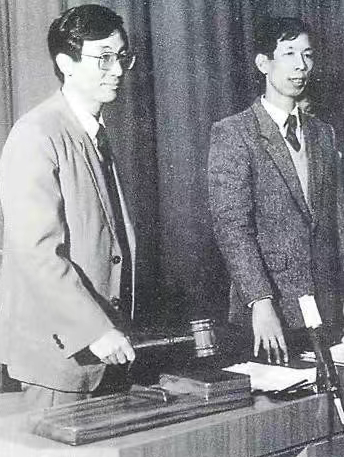

Recalling that historic moment, the auctioneer Liu Jiasheng—who later became the Director of Shenzhen’s Bureau of Urban Planning and Land—said:“I can still feel the heartbeat from that day!”

Amid doubts and misunderstandings, and after 17 minutes of intense bidding, the final gavel fell. The Shenzhen SEZ Real Estate Company successfully bid 5.25 million yuan

This single auction triggered a chain reaction in Shenzhen and across China. On December 29, the Guangdong Provincial People’s Congress Standing Committee passed the “Shenzhen SEZ Land Management Regulations”, which explicitly allowed paid transfers and assignments of land-use rights.

Soon after, many cities across China adopted Shenzhen’s model, initiating paid transfers of state-owned land.More importantly, on April 12, 1988, during the First Session of the Seventh National People’s Congress, a constitutional amendment was passed. The previous ban on “leasing” land was removed, and the new provision stated:“The right to use land may be transferred in accordance with the law.”At the time, the media hailed this as:“A historic breakthrough and a fundamental transformation in China’s land-use system. It signified that the nation’s Constitution now recognized land-use rights as a commodity, marking a monumental step toward the marketization of land.”

The first generation of Shenzhen pioneers took enormous risks—not for fame, but for development.

Since that groundbreaking auction, Shenzhen has continued to explore reforms in land management, providing powerful support for its social and economic development.

Shenzhen is a city with a large population and a strong economy, yet it is land-scarce. Facing different land management challenges at various development stages, Shenzheners have used reform and innovation to carve out new paths in land use, setting an example for the entire country.

In 1992 and 2004, Shenzhen implemented unified land acquisition and transfer. All rural collective land was converted into state-owned land, turning villagers into residents, village committees into neighborhood offices, and village assets into joint-stock company assets. With all collective land reclassified as state-owned, Shenzhen achieved complete urbanization, becoming the first city in China without any rural villages.

Shenzhen has painted infinite possibilities on its limited land:Large-Scale Area Development: The city identified 70 contiguous development zones, covering about 100 square kilometers. This broke away from fragmented land-use patterns, using coordinated development to enable large projects and attract enterprises through clustered resources and industry ecosystems.

“Vertical Industry” Development: When ground space wasn’t enough, Shenzhen looked to the skies. The city pioneered the concept of “industry in high-rises,” concentrating production facilities and supply chains in the same building.“Upstairs and downstairs are upstream and downstream; one building is one industrial chain; the industrial park is an ecosystem.”Today, this model is expanding across China.

“Flying Land Economy”: To break spatial limits, Shenzhen established the Shenshan Special Cooperation Zone in December 2018—its “10+1” district—adding 468.3 square kilometers of new development space.

The region adopted a “one core and three auxiliary” industry structure: new energy vehicles as the core, with energy storage, new materials, and intelligent manufacturing as complements—fully integrated into Shenzhen’s industrial system.

The fall of one auction hammer led to comprehensive activation across Shenzhen’s land system. Through continuous exploration and bold reform, this land-scarce city produced an economic miracle, becoming a vanguard in China’s broader reform and opening-up strategy.