The legend of Cao Jianyou began in 1936 — with what he would later call a “decision of destiny.”

At just nineteen, he stood before a life-altering choice: selecting his major at Shanghai Jiaotong University. The Department of Electrical Engineering required the highest admission score, while Mechanical Engineering came second. Born into a poor family, Cao could not afford hesitation. He wrote the two majors on slips of paper, rolled them into ten small balls, and drew them one by one. To his astonishment, all five draws bore the same word — “Electricity.”

“Heaven’s will it is!” he laughed. With that, he enrolled in the Department of Electrical Engineering, ranking fourth in his class — sealing a lifelong bond with the world of power and current.

During his studies in the United States, Cao Jianyou earned his Ph.D. at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). His academic brilliance led his advisor to offer him a permanent lecturer position. Shortly after, City University of New York extended an even more generous offer — an annual salary of $6,000, an impressive sum in the 1940s.

But history soon called.

In 1950, when the Korean War broke out and the Chinese People’s Volunteers crossed the Yalu River, Cao’s heart burned with patriotic urgency. Under the guise of “visiting an ailing relative,” he quietly left the United States with his wife and daughter, taking a month-long journey through San Francisco, Manila, and Hong Kong, finally returning to the newly founded People’s Republic of China.

“Returning home to serve my country is the most important thing in my life,” he told his students firmly.

Upon his return, both the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Qian Weichang personally invited him to join national laboratories — to study particle accelerators and to help found the Institute of Automation. Yet Cao declined both offers. Instead, he chose to go where no one else would — to the Tangshan Railway Institute (the predecessor of today’s Southwest Jiaotong University).

“The field of railway electrification is a blank slate in China,” he said. “Someone has to break the ground.”

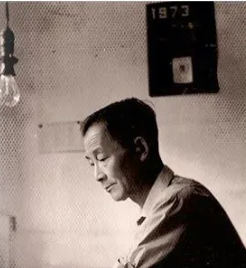

In 1953, design work began for China’s first electrified railway — the Baoji–Fengzhou section. Soviet experts, who were then China’s main technological partners, strongly recommended adopting the 3000V direct current (DC) system.

Cao Jianyou, however, presented a revolutionary alternative: 25kV single-phase 50Hz alternating current (AC).

It was a daring move. China at the time was in a period of “leaning to one side,” following Soviet standards almost without exception. His proposal met with heavy skepticism. Experts labeled it “unrealistic.” Even students mocked his son, teasing, “So, is your house electrified yet?”

But Cao stood firm. In 1956, he published a landmark article in People’s Daily titled “The Path to Railway Electrification in China.” In it, he used rigorous data to prove that the DC system required a substation every 20 kilometers — exponentially increasing costs in mountainous regions — while the AC system, with eight times the voltage, offered vastly superior transmission distance and power efficiency.

In 1957, the Ministry of Railways officially adopted Cao Jianyou’s proposal, designating 25kV single-phase 50Hz AC as the national standard for railway electrification.

By 1960, the Baoji–Fengzhou segment of the Baocheng Railway was redesigned and successfully energized under the new system. This moment marked the beginning of China’s railway electrification, aligning it directly with the world’s most advanced standards.

Cao’s vision spared the nation from repeating the costly “DC-first, AC-later” detour taken by other countries — saving enormous resources and paving the way for the future rise of China’s high-speed rail.

Today, as China’s high-speed trains glide across the land at 350 km/h, the heart of their power — the traction and supply system — still beats in rhythm with Cao’s 25kV AC standard. Many countries that once favored DC have since followed this same path.

When Cao was assigned in 1952 to establish China’s first Railway Electrification Department, the nation had not one kilometer of electrified track, no textbooks, and no trained teachers.

He mobilized every resource available — contacting international railway offices, retrieving data through the Chinese embassy in the Soviet Union, translating foreign textbooks by hand, and even founding China’s first railway automation research institute.

These efforts laid the groundwork for a discipline that would transform China’s industrial and transportation future.

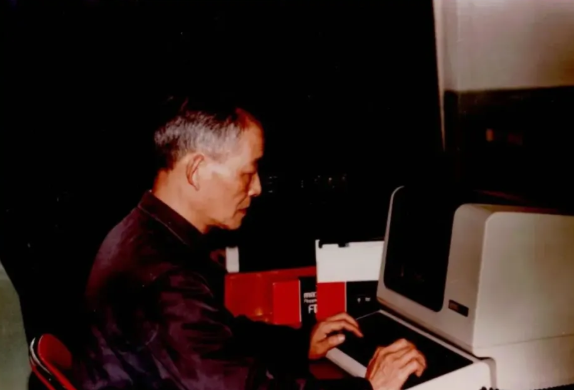

In 1978, at age 61, Cao Jianyou became vice president of Southwest Jiaotong University. A decade later, in 1988, the school received a notice to apply for a National Key Laboratory designation. The leadership decided that both the Mechanical and Electrical Engineering departments would submit a joint proposal — with Cao overseeing the entire process.

Eighteen research directions were proposed, but Cao placed his support behind Professor Shen Zhiyun’s project: establishing the National Key Laboratory of Traction Power.

“National investment is limited,” he said. “If we try to build everything, we’ll build nothing. The future lies in high-speed rail. To develop it, we must create a rolling-vibration test platform for locomotives and carriages. Germany has one in Munich. If we aim higher — to surpass theirs — China will hold the key to mastering its own high-speed train technology.”

Cao organized four rounds of internal defense rehearsals to ensure perfection. In the end, the proposal ranked 27th nationwide and passed the national review successfully. For many years, it remained the only National Key Laboratory within the railway system.

By 1995, the lab passed its final national evaluation. The Traction Power National Key Laboratory at Southwest Jiaotong University became China’s most important testing and verification center for high-speed rail models — a platform through which every new train type must pass before entering service.

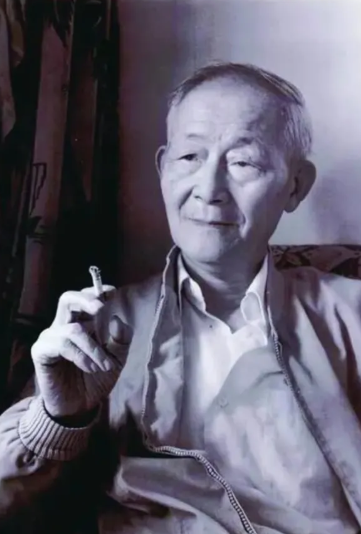

In his later years, Cao Jianyou often reflected on his life in his diary.

“What I think of most often,” he wrote, “is Zhuge Liang’s line — ‘To dedicate oneself wholly until death.’”

He joined the Communist Party of China at eighty years old, humbly noting, “I know what I can still do is limited. But I want to keep trying, consciously, purposefully.”

As the founding father of China’s railway electrification, Cao once summarized his life’s work with quiet pride:

“We avoided taking the wrong path in the question of current systems. That, I think, is my small contribution to the motherland.”

Cao Jianyou’s story is not just one of technical innovation — it is the chronicle of a man who chose the harder road for the sake of his country’s future. From a coin toss of fate to the roar of high-speed trains, his life embodies the spirit of a generation who believed that knowledge, once brought home, could power a nation.

Through his unwavering faith in science and service, Cao didn’t just electrify China’s railways —

he electrified the very soul of a nation on its path to modernity