Among the vast sea of China’s folk arts, the dragon dance has always stood out as one of the most vibrant and enduring cultural symbols. In Pujiang County, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, a unique form of dragon dance known as the “Bench Dragon” rises with unmatched vigor and flair. With its bold and unrestrained movements, combined with agile, ever-shifting formations, the Bench Dragon has become a treasured gem among China’s national intangible cultural heritage. It is more than just a festive performance — it is a living memory of the land and its people, a heartfelt prayer for favorable weather and peace throughout the nation.

The origins of the Pujiang Bench Dragon trace back to the Tang Dynasty. According to legend, during the Zhenguan period, Pujiang suffered a long and devastating drought. People were in extreme hardship. A Taoist priest advised the villagers to link wooden benches together in the shape of a dragon and dance through the streets to pray for rain. Miraculously, soon after, rain began to fall, and the crops were saved. Since then, the Bench Dragon has become a ritual for Pujiang locals to pray for peace and blessings, gradually evolving into a distinctive folk art. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Bench Dragon was flourishing in Pujiang.

Historical records reflect its popularity. The Qing Dynasty’s Pujiang County Annals recorded: “During the Lantern Festival, a dragon is formed with benches, stretching for dozens of segments, winding through city streets, and spectators crowding all around.” This vivid description speaks volumes of the grand scale it once held.

Over the course of hundreds of years, the Bench Dragon has been passed down through generations. What began as a simple rain prayer ritual has developed into a complex performance that marries artistry with athleticism. The craftsmanship has grown more sophisticated, and the symbolism more profound.

A complete Pujiang Bench Dragon is typically composed of dozens or even hundreds of wooden benches connected in series, forming a dragon that can stretch several hundred meters in length. Each bench is, in itself, a standalone piece of art. Cedar or camphor wood is most commonly used due to its lightweight yet resilient properties—ideal for dancing with.

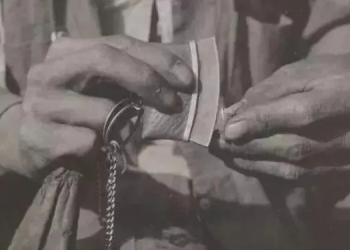

Each bench serves as the skeletal frame of the dragon. Holes are drilled at both ends and joined with wooden rods or iron rings, enabling the dragon’s body to twist and sway with remarkable flexibility. The decorations are meticulous and vibrant: the dragon’s head is crafted with bamboo strips, adorned with colorful paper and silk, its eyes wide and spirited, whiskers flying high — vividly lifelike. The body is dressed with hand-painted scales, gold foil, or painted clouds, sparkling in the sunlight. The tail is often styled like a fish’s tail, symbolizing the auspicious legend of the carp leaping over the dragon gate

Among the many impressive aspects of the Bench Dragon are its elaborate formations. One of the most breathtaking is the “Panlong” (Coiled Dragon): in an open space, the dragon connects head to tail, coiling into a massive circle that symbolizes completeness and harmony. Another is “Fanlong” (Flipping Dragon), in which the dragon rapidly flips and waves like a surging tide — an awe-inspiring display of energy and unity. These complex moves test not only the dancers’ strength and skill, but also reflect the spirit of solidarity and perseverance that defines the people of Pujiang.

Like many traditional arts, the Bench Dragon has faced the threat of decline in modern times. As younger generations moved to urban centers for work, and veteran artisans aged or passed away, the skills and knowledge that sustained the Bench Dragon began to fade. For a time, the very survival of this living tradition hung in the balance.

Fortunately, in recent years, both governmental and grassroots efforts have reignited its flame. Pujiang County established dedicated transmission bases to safeguard the Bench Dragon’s legacy. Veteran artisans were invited to teach not only the crafting techniques but also the choreography and ritual aspects of the dance. Schools introduced programs to spark children’s interest and nurture new generations of inheritors.

To ensure the Bench Dragon thrives in the modern age, young successors have infused new energy into the tradition. Innovations include using lightweight modern materials for easier movement and incorporating audiovisual effects — sound, light, and projection — to make performances more captivating for contemporary audiences.

The cultural promotion efforts have also broadened. The Pujiang Bench Dragon has graced domestic and international folk festivals and even took center stage at the CCTV Spring Festival Gala — China’s most-watched television event — showcasing this ancient art to a global audience.

The Pujiang Bench Dragon is a living embodiment of China’s agrarian memory and a vivid expression of the people’s wisdom. It is not merely an artistic performance, but a sacred ritual that encapsulates reverence for nature, love for life, and hope for the future.

In an age of rapid urbanization, cultural treasures like the Bench Dragon remind us that true heritage lies not in rigid preservation but in dynamic renewal. The past is honored not by keeping it locked away, but by allowing it to live, breathe, and evolve with each generation.

As the drums beat and the dragon lights glow once more, what we witness is not just a performance — it is a thousand-year cultural symphony unfolding before our eyes.

May the Bench Dragon continue to dance in the mountains and rivers of Pujiang.

May it forever pulse in the bloodline of Chinese civilization.